On January 20, 2025, Donald Trump withdrew the United States, the largest historical greenhouse gas emitter and second-largest annual emitter currently, from the Paris Agreement for the second time and promised record fossil fuel expansion. With that, the 1.5 degrees Celsius goal that was already on life support earlier is now decidedly out of reach. It may even arrive earlier than expected if global emissions soar due to Trump’s climate policy backtracking and its knock-on effects, counteracting the emission reductions from the rest of the world and other large emitters such as China.

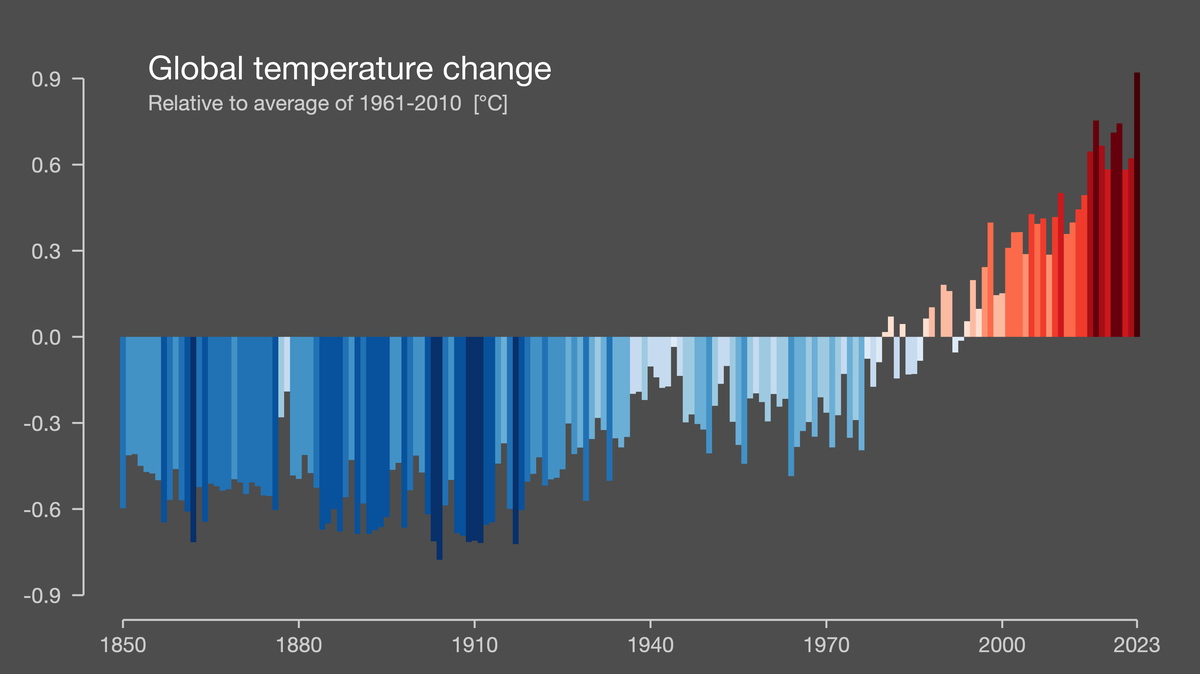

For a vast country like India, the challenges from climate impacts are not only numerous but can also be drastic, severely impacting development goals. 2024 being the first time any single year has crossed 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming and the hottest ever, probably in the whole of human history — about 1.6 degrees Celsius warmer than pre-industrial levels — is a grim and symbolic marker of the world’s failure to limit warming.

Global temperature change

| Photo Credit:

Ed Hawkins (https://showyourstripes.info/c)

This portents turbulent times ahead for India in dealing with the fallout of increasing emissions and breaching 1.5 degrees of long-term warming in the near future (2030s). But what exactly does it mean for a highly populated and climate vulnerable, developing country with diverse geographies, a growing economy and great inequalities? We ask leading climate scientists to weigh in on what India at 1.5 degrees Celsius would look like and how to prepare for changes that were expected by 2100 but are now imminent in the coming decade.

What is the 1.5 degrees goal?

Not what it seems: Many people wrongly believe the world is coming to an end as 2024 becomes the first-ever year to breach 1.5 degrees of warming, signalling the failure of the 2015 Paris Agreement. However, this is not true. The agreement refers to long-term warming, which would require at least 20 or 30 years to consistently record annual temperatures of over 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to the pre-industrial average. 2024 marks only the beginning of this trend, but it is still a rude wake-up call of a symbolic milestone that has been breached, on the 10th anniversary of the landmark treaty, no less.

Not when the world ends: 1.5 degrees Celsius is neither a tipping point where things drastically spiral out of control nor a physical limit defined by science where the world ends. 1.5 degrees Celsius was a political and an economic choice, something that countries and world leaders could accept, rally around and plan for. Scientists have not identified any amount of warming as the optimal or as a defence line drawn in sand. What they have said with certainty is that every tenth of a degree of warming increases the risk of extreme weather events, frequency and intensity of disasters, and ecosystem collapse.

What it actually means: 1.5 degrees Celsius is a lodestar that has helped catalyse global ambition on climate action, providing a tangible goal post against which countries, organisations and communities can plan their mitigation and adaptation strategies. It helps provide a meaningful way to translate the latest climate science into policy relevant insights, to understand and predict climate impacts, measure progress, and design safe pathways to net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

Extreme heat

People queue up for water during a heatwave in Delhi last June.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Last year’s heatwave sent shockwaves around the globe when Delhi, one of the world’s most populated capitals with a large section of people in highly vulnerable conditions, recorded temperatures as high as 52.3 degrees Celsius, prompting both fear and scepticism if perhaps a faulty sensor was responsible for the confusion. However, 50-degree days are already becoming more frequent around large parts of the country as the global temperature rises.

Krishna AchutaRao, Dean and Professor at the Centre for Atmospheric Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, says, “The effect of even a small change in the tropics is significant because we are already at the edge of what is possible to live with — be it extreme temperatures or rainfall. The full extent of the impacts we face — either from the slow-moving changes in the mean or the increased extreme events — is not yet fully accounted for.”

In order to help climate science inform adaptation policy, his group at IIT Delhi analysed future heatwaves over India in both 1.5 degrees Celsius and 2 degrees Celsius warmer worlds. In a recent study, they found higher extremes in temperatures are unlikely, but the increasing coverage is more worrisome. “The likelihood of large parts of the country experiencing two-month-long heatwaves is alarmingly high and we are not prepared for such events. The chance of heatwaves into July are also projected to increase, which is an alarming prospect considering that the monsoon would have set in already by then and the humidity will be high,” says AchutaRao.

“The effect of even a small change in the tropics is significant because we are already at the edge of what is possible to live with — be it extreme temperatures or rainfall”Krishna AchutaRaoDean and Professor, Centre for Atmospheric Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi

Previous studies have found that high humidity can create dangerous conditions even in seemingly lower temperatures due to the inability of the human body to thermoregulate and cool itself down through sweating. Another study found that 3.7 billion people in the tropical belt, which includes peninsular India, will be at high risk of high humidity-induced heat stress nearing the human physiological limits if temperature crosses 1.5 degrees Celsius. Humidity is the reason why the dry heat of Delhi or Hyderabad seems much more bearable than the humid summers of Mumbai or Chennai.

However, beyond heat stress, heatwaves can cripple communities, systems and economies in several ways. In another recent study by AchutaRao’s research group, the team mapped the various ways the 2022 heatwave impacted crucial sectors such as health, economy, agriculture, environment and transport. The authors highlight that rising temperatures will render coping mechanisms inadequate, leaving the urban poor the most exposed and vulnerable to extreme heat. “We could have a nationwide summer-long heatwave, where more fundamental issues like food and water security will be tougher to face,” he says.

Impact of ocean warming

A milkman cycles through a waterlogged road in the wake of Cyclone Dana in Kolkata, October 2024.

| Photo Credit:

ANI

While the Bay of Bengal has always been known to bring devastating cyclones to the eastern coast, prompting excellent disaster response, the western coast, which was previously safe from this type of disaster, is now being forced to learn how to cope with destructive tropical cyclones, thanks to climate change. For example, 2020’s Cyclone Nisarga was the first to hit Mumbai in June in over 100 years, but will not be the last anymore. Latest research says the intensity of cyclones has increased in the Arabian Sea by 40% pre-monsoon and 20% in the post-monsoon season, and the number of cyclones increased by 52% over the last four decades, along with a projected increase in the frequency of cyclones in the future.

Roxy Mathew Koll, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, says the Indian Ocean is warming at a rapid pace. Climate models predict accelerated warming, at a rate of 1.7°C to 3.8°C per century during 2020-2100, with the Arabian Sea experiencing maximum warming.

“Cyclones are becoming more intense, forming rapidly, and lasting longer. The storm surges caused by these cyclones, combined with sea-level rise, lead to prolonged and severe coastal flooding,” says Koll, on one of the major impacts of rising ocean heat.

The Indian Ocean and its surrounding countries stand out globally as the region with the highest risk of natural hazards, according to Koll, with coastal communities of nearly 40 countries bordering this ocean vulnerable to weather and climate extremes. The Indian Ocean is also moving to a near-permanent marine heatwave state, with periods of extremely high temperatures in the ocean expected to increase from 20 days per year to 220-250 days per year.

“As we cross the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold, curbing fossil fuel emissions remains critical to slowing global warming. However, achieving this requires a transformational global effort, which has been lacking. In a country like India, where fast-moving tropical weather systems can devastate large populations, we cannot wait for the globe to act. Our lives and livelihoods are at stake,” he adds.

“Cyclones are becoming more intense, forming rapidly, and lasting longer. The storm surges caused by these cyclones, combined with sea-level rise, lead to prolonged and severe coastal flooding”Roxy Mathew KollClimate scientist, Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology

Too much water, too little water

A waterlogged street in Chennai after a heavy spell of rain in October 2024.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

Every monsoon, India is increasingly seeing costly disasters compounded by extreme rainfall events such as last year’s deadly Wayanad landslide in Kerala, which claimed over 250 lives and recorded over ₹1,200 crore in damages.

The latest Global Water Monitor report finds water-related disasters caused major damage in 2024, causing over 8,700 deaths, displacing 40 million people, and inflicting more than $550 billion in damages. In comparison, the total pledges from developed countries to help all developing countries adapt to the impacts of climate change from all types of disasters is only $100 billion per year. Flash floods, landslides, and tropical cyclones were the worst types of disasters in terms of casualties and economic damage.

Vimal Mishra, a professor at the department of Civil Engineering and Earth Sciences, IIT Gandhinagar, whose research focuses on climate change and hydrologic extremes says, “The hydrological cycle will be intensified under the increased warming, with notable rise in extremes — rainfall extremes, floods, droughts, compound hot and dry extremes, and whiplashes. Multi-day extreme rainfall events can cause large floods, disrupting agriculture and infrastructure.”

Beyond the clearly visible “excess” water related disasters, slow moving, invisible impacts such as groundwater depletion and droughts are also a major concern in an agrarian country with low productivity and infrastructure ill-equipped to deal with water extremes, where even small changes in water availability can lead to significant damages.

According to Mishra, higher warming will cause hotter and shorter flash droughts enhancing the irrigation water demands, which can lead to more groundwater pumping as seen in North India that has already experienced a rapid depletion of groundwater storage in the last two decades. Increased warming will also cause more variability in the Indian summer monsoon leading to more floods and droughts during the same season with profound implications for water and food security.

Melting mountains

Damaged roads in Teesta Valley due to a landslide in Sikkim.

| Photo Credit:

Praful Rao

According to a study, at 1.5 degrees of warming, nearly half of the world’s glaciers will melt by 2100. Today, 79% of all glaciers are small, with less than 1 sq.km. area and of them, nearly 60% will be lost at 1.5 degrees of warming. The Hindu Kush Himalaya region also experiences elevation-dependent warming, due to which the high-altitude region has warmed by over 2 degrees Celsius.

This means several mountain communities that depend on glaciers for agriculture and sustenance in the Himalayas will be parched. And being in remote, rain-shadow regions with no rainfall or energy access, their lives will be upended, also leading to migration and emptying of mountain villages. This is already underway, and set to become more severe in future. Additionally, they face several glacial and cryosphere hazards such as glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), avalanches, debris flows, cloudburst cascades and permafrost degradation.

In a recently published paper analysing the devastating Sikkim flood in 2023, the researchers found permafrost thaw to be one of the major drivers of South Lhonak lake’s outburst flood.

Lead author of the study, Ashim Sattar, Assistant Professor at School of Earth, Ocean and Climate Science, IIT Bhubaneswar, whose research focuses on glacial modelling and GLOF, says, “Widespread permafrost [frozen ground] in the high mountains is becoming warmer with time, thereby increasing the susceptibility of the mountain slopes to potential failure, leading to ice-rock avalanches that can impact infrastructure. Hydropower too will be impacted as many hydropower projects are constructed in high mountains in valleys fed by glacier melt, and are also susceptible to GLOFs due to their locations.”

“Even before we breach the 1.5 degrees Celsius temperature goal, adaptation has been a pressing imperative, especially in India where a large population is exposed to climate risks and is deeply vulnerable because of non-climatic factors such as poverty, unemployment, infrastructure deficits, etc.”Chandni SinghLead at School of Environment and Sustainability, Indian Institute for Human Settlements

GLOFs are expected to triple in the High Mountain Asia landscape by the end of the century, as per one study. And incidents such as Sikkim’s South Lhonak disasters are likely to become more frequent and cost billions in damages. “If we look into the GLOF hazard situation in the Himalayas, the eastern and central Himalayas have been identified as the regional hazard hotspot in the present. However, this hotspot is expected to shift towards the western Himalayas in the future,” says Sattar.

While the relationship between increasing temperatures and extent of glacial melting can be pretty straightforward, glacial lake outburst floods are not so easy to predict or model due to uncertainties in the various triggers and failure mechanisms of the lakes and moraine or ice dams. Sattar believes there will be more clarity on this going forward as research is emerging on this topic, but it is impossible to accurately predict the timing of failure of the several thousands of glacial lakes that have formed over the recent years and are rapidly expanding at the moment.

The way forward

Tourists being rescued after landslides in Sikkim, June 2024.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

From a knowledge standpoint, India is no longer lacking in scientific expertise, relevant data or in-depth understanding of various climate extremes. However, integrating the latest information to enact climate-aware policy remains a huge challenge as the adaptation response is still scattered and limited.

According to Mishra, “India should enhance early warning systems and combine indigenous and local knowledge with technological advancement to develop successful climate adaptation approaches, addressing groundwater resource management, reservoir operations, maintaining crop yields, enhancing prediction of extreme weather and climate events.”

Chandni Singh, a leading researcher working on climate adaptation and Lead at the School of Environment and Sustainability, Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS), says, “Even before we breach the 1.5 degrees Celsius temperature goal, adaptation has been a pressing imperative, especially in India where a large population is exposed to climate risks and is deeply vulnerable because of non-climatic factors [poverty, inequality, unemployment, infrastructure deficits, etc].” Observing that we do have a range of feasible options, many of which India is already implementing, she says the gaps remain in moving beyond sectoral solutions to systemic ones. “This is tougher and requires simultaneous transitions across various systems — agriculture, energy, infrastructure, society — which is currently not happening at the speed and scale required,” says Singh.

Additionally, IIHS’ ongoing research on pathways to the 1.5 degrees Celsius goal found that the current funding for adaptation in India is grossly inadequate even though there has been an increased focus on improving adaptive capacity in vulnerable sectors. Climate finance is also skewed in favour of mitigation (about 90%) with only about 10% investment for adaptation.

While all the scientists interviewed for this article lament the lack of global ambition to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, they stress on the urgent need to use latest science to inform policy.

Koll says, “We urgently need to tailor adaptation plans and policies based on the climate risks we face locally. Achieving this requires collective action supported by strong political will, adequate financing, scientific expertise, and interdepartmental cooperation.”

Even while acknowledging more is needed, Singh remains hopeful. “The government has been taking promising steps in involving researcher and practitioner communities on various aspects of climate action — from expert workshops on loss and damage, to annual national workshops on heat preparedness and risk management. These are promising and pave the way for evidence-based policy making.”

The writer is an independent journalist and filmmaker covering climate change in the Himalayan region and South Asia.

Published – January 31, 2025 11:50 am IST