More absenteeism, worse handwriting and more technology in the classroom — these are just a few of the changes San Antonio teachers said they’ve noticed in elementary students in the five years since COVID-19.

Students across the country left for spring break in March 2020 and most didn’t physically go back into the classroom until almost one year later, doing online learning to reduce the spread of the deadly coronavirus.

Five years later, San Antonio’s more than 83,000 students are back on campuses, but the effects of forced remote learning linger.

The San Antonio Municipal Court launched an “Attendance Matters” campaign in 2023 to address the issue of chronic absenteeism and encourage students to go to school.

To check in on what has changed, the Report spoke with three elementary school teachers who work at schools in San Antonio Independent School District about the education landscape now that they’ve had five years of space between them and the 2020 pandemic.

Math is harder than reading

Overall, math test scores have not gone back to pre-pandemic levels, meaning most students are not meeting grade level criteria and fewer are mastering the content, data from the Texas Education Agency shows. However, the most current reading test scores show more students demonstrate that they’re on grade level or mastering the content compared to the 2018-2019 school year.

Elizabeth Rodriguez, a fourth grade teacher at Agnes Cotton Academy in SAISD who covers all core subjects, said students may be scoring better in reading because it’s an “easier subject to teach.”

“I think the parents did their part to get their kids to read” while classes were held online, Rodriguez said. “We all kind of know how to read, and we can support our kids in that.”

But when it comes to math, parents are less familiar with the material and may struggle to help their students with the subject, which leads to more “gaps in the foundation” Rodriguez said.

A look at pre-pandemic STAAR results for fourth grade students enrolled in Region 20 schools in 2019, which includes San Antonio and stretches towards a southwestern portion of the Texas-Mexico border, shows that 41% tested on grade level and above and 23% mastered the content.

During the height of the pandemic in 2021, only 28% of students in the region scored on grade level and 16% showed mastery.

But fourth graders seem to be scoring better now, even if they’re not back at pre-pandemic levels. The most recent scores show 39% of fourth graders scored on grade level, while 17% showed mastery of the content.

Math test scores for fourth graders in SAIAD showed that 30% tested on level and 16% mastered in 2019. But in 2024, only 27% of test takers scored on grade level and 10% demonstrated mastery — TEA data shows these scores were slightly lower compared to 2023 scores but significantly higher than in 2021.

When looking at overall reading and math proficiency in San Antonio, an analysis of test results for third grade through eighth grade by City Education Partners shows that students had a math proficiency of 34% in 2022, which decreased to 31% in 2024.

Data about student performance and attendance before 2022 is not available through City Education Partners.

Reading scores soared

Before the pandemic, 34% of Region 20 fourth graders scored on grade level while 15% mastered the subject. But in 2024, 53% of sixth graders who took the STAAR tested on grade level and 22% mastered.

On a smaller scale, similar increases in reading scores for students in third grades through eighth grade took place in districts like Edgewood Independent School District, Northside Independent School District and SAISD.

The increases are similar for fourth grade students at Cotton Academy, where Rodriguez works.

TEA data shows that in 2019, 27% of fourth graders who took the reading STAAR at Cotton Academy were on grade level and 14% showed mastery. Results from 2024 showed that 49% of fourth graders were on grade level and 19% mastered the content.

But comparing STAAR scores from 2019 to test scores after 2023 may not be the best way to measure how students are doing, said Deja Hook, a fifth grade teacher who also teaches all core subjects at Cotton Academy.

Before the 2022-23 school year, STAAR tests underwent a “redesign” with the enactment of House Bill 3261 in 2021.

Previously taken with pencil and paper, students now take the standardizes tests online, and tests undergo a hybrid scoring process of AI technology and human review.

“It’s very hard to compare apples to apples. Like, everybody’s saying we haven’t come back from COVID yet. But like, how do we know if they’re not taking the same style test for STAAR?” Hook said.

Hook also said the state lowered the STAAR grading threshold for students to meet the different scoring categories of “approaches grade level,” “meets grade level” and “masters grade level” after 2020.

As for why a larger percentage of students seem to be scoring higher in reading compared to math, Hook shares the same explanation as Rodriguez: reading is simply easier than math.

“You could probably go four or five months without reading a book and pick up a book — you’re still going to know how to read the book. But if you didn’t get four or five months of instruction in math, and then all of a sudden, people are throwing all this stuff at you, like you have no clue,” Hook said. “I think that’s where the big breakdown for the math is.”

Chronic absenteeism and student behavior

Chronic absenteeism rates for SAISD were 40.6% during the 2022-23 school year, which is more than double the rate for the 2019-20 school cycle.

For Cotton Academy, chronic absenteeism rates reached 24.2% during the 2022-23 school year, a huge jump from 2019-20, which saw a total of 4.6% of students who were chronically absent.

In Texas, students who miss at least 10% of school days, whether they are excused absences or not, are considered chronically absent.

City-wide, 33% of students in third grade through eighth grade were chronically absent in 2022, according to CEP data.

Julie Vallery, a physical education teacher at Barkley-Ruiz Elementary, said she’s noticed the trend of students missing school in her gym classes.

“I would have kids straight up tell me ’Oh, my mom said I didn’t have to come.’ What do you mean your mom said you didn’t have to come? It’s required,” Vallery said. “We had to kind of retrain the parents to bring [students] to school every day.”

At Barkley-Ruiz, chronic absenteeism was 12.8% before the pandemic and reached 53.2% for the 2022-23 cycle.

One explanation for why more students are skipping classes is that parents are more cautious about their students’ health since the pandemic, which results in more absences, education experts say.

“In COVID, you know, health and safety are the priority, as it should be, but I feel like now … parents are still in that mindset,” Rodriguez said.

Missing school often also leads to poorer student outcomes.

A 2022 analysis from City Education Partners shows a negative correlation between chronic absenteeism and reading and math proficiency in students in third through eighth grades.

Chronic absenteeism data from City Education Partners and TEA is not available past the 2022-23 school year.

Outside of the absenteeism, Vallery, who’s been teaching for more than 20 years, said students talk more during class and seem to lack motivation after coming back to the physical classroom.

“I mean it’s slowly getting better… but those first couple of years after COVID were very, very difficult discipline-wise and just trying to get them back into the routine of things,” Vallery said.

Vallery has two high school seniors enrolled at Northside ISD who she said are doing well despite the COVID interruption.

“I don’t know if it’s the neighborhood that I’m teaching in, or if it’s COVID, or if it’s parent involvement,” Vallery said.

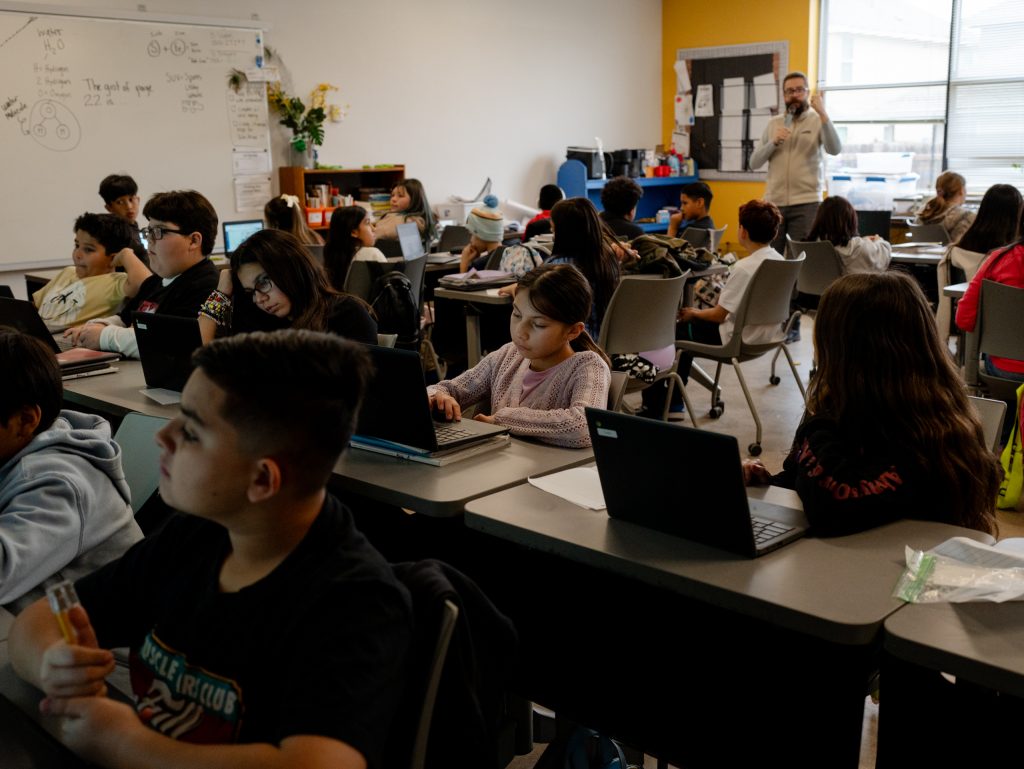

More tech in the classroom

In terms of change in her own classroom five years after being forced to teach virtually, Rodriguez — a teacher of 16 years — said there have been upsides.

One of the positives Rodriguez noted was the increased use of technology for her classes. When schools shut down as a precaution against COVID-19, classes were moved online, which meant an increased use of computers, smartphones and virtual communication services like Zoom and programs that relied on the internet instead of paper and pencils.

Rodriguez said that using more technology was a good thing, because it forced her and her students to become tech-savvy. Using more tech also promotes student engagement and helps them adjust to an increasingly technology-reliant world, she said.

But being in lockdown also showed Rodriguez that students need social interaction.

“Even with the user technology, I feel like kids and teachers just flourish better when we’re working together as a community versus in isolation,” Rodriguez said.

Even though she worries students spend too much time in front of screens, Hook agrees that the increased use of technology is one of the good things to come out of virtual learning during the pandemic.

“We didn’t have great technology at our campus before COVID,” Hook said. “And now [fifth graders are] learning how to manage Google Drives, and are learning how to create presentations via Slides or Canva or iMovie.”

But for some assignments, Hook said she prefers students to use pencil and paper, event though her students’ handwriting became largely illegible after COVID. Sometimes, Hook has to ask her students what their handwritten assignments say.

“They didn’t know the holes go on the left side [of notebook paper]. … A lot of times the paper was backwards, or the paper might be upside down. And I was like ‘Oh no,’” Hook said. “I was just like, whoa. Like, this is kind of scary.”

With each new cohort of students, Hook says she is seeing some improvements in the handwriting area.