Family photograph

Family photographNearly 60 years ago, when Karen Teasdale-Robson was just nine months old, her father wrote her a lullaby.

In a family burdened by violence, Brian Teasdale looked after her and sang Little Girl whenever she was sad.

But, his daughter says, when an assault by his own son left him with brain damage she thought she would never hear him sing again.

Family photographs

Family photographsLife at home was not always easy, says Mrs Teasdale-Robson, who now lives in Newcastle.

Her mother and brother had mental health problems and she says she and her father were on the receiving end of violence from them both.

“My dad was the only loving person in my life then,” she says. “He got me out of the house and took me out for walks away from the nastiness.

“I think he was bewildered by my mam’s aggression. He tried to keep me out of it and make sure I felt loved.”

Mrs Teasdale-Robson believes her father worried his wife would get custody if the couple split up and so stayed for his daughter.

“Our whole lives were spent trying not to upset her,” she says.

Family photograph

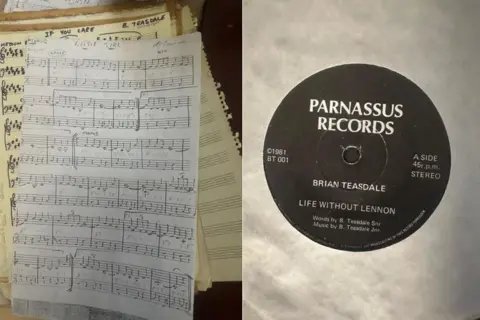

Family photographMr Teasdale was endlessly creative, winning a poetry competition when he was eight and learning to play the guitar and “constantly” writing music, his daughter says.

“He even wrote a song in memory of John Lennon after he died and sent a copy on vinyl to Yoko Ono.”

He did everything for his daughter when she was young because his wife was not well, she says, and it was during this time he wrote Little Girl.

“He used to sing it to me and say ‘this is your song, Karen’.”

But, in October 2011, everything changed.

“My dad was assaulted one final time by my brother,” Mrs Teasdale-Robson says. “He left my dad with a serious brain injury.”

Her father lost the ability to communicate beyond one or two words at a time and could no longer write.

“He went from being a man who was a master of words – a man of intellect – to me teaching him to speak,” she says.

Karen Teasdale-Robson

Karen Teasdale-Robson“They said it could take years to establish what capacity he had left but I knew he was in there somewhere,” Mrs Teasdale-Robson says. “So I recited one of his poems.

“My dad couldn’t say a word, but he made sounds along with the meter of the poem. The neuropsychologist said she got goosebumps.”

She bought children’s books and read to her father every day.

“The day he said my name that December was the greatest Christmas gift I ever got,” she says.

Karen Teasdale-Robson

Karen Teasdale-RobsonIn 2012, Mr Teasdale was moved to a specialist residential brain injury unit, Chase Park, in Whickham, where his daughter visited him every day.

“He would say things like ‘don’t forget me’ and ‘I used to be clever’. It broke my heart,” she says.

“I knew what it would do to him, not being able to write. The thought of his work being lost. I promised him there and then that I’d get his work seen.”

When, in 2021, during the Covid pandemic, Chase Park warned Mrs Teasdale-Robson her father did not have long left to live, she “panicked at the thought of him dying with people not knowing how talented he was”.

Karen Teasdale-Robson

Karen Teasdale-RobsonNot long afterwards she was looking through an old briefcase when she came across an ageing, brown reel-to-reel tape-recording of her lullaby. A shop in the city put it on CD for her and she says it was “unbelievable to hear him singing again”.

But the recording had deteriorated and her beloved song was crackly and distorted.

She turned to BBC Radio Newcastle for help and her appeal reached one of the lecturers in Sunderland College’s music department.

Tony Wilson says, when he played the recording to his students, they immediately wanted to re-record it.

“The entire room was stunned by the sheer beauty of it,” he says.

“It struck me immediately as being up there with those old classics from the American Songbook. It had a real quality of something like Somewhere Over the Rainbow or Blue Moon.”

Sunderland College

Sunderland CollegeWhen Mrs Teasdale-Robson heard the new version she “couldn’t stop crying”, she says.

“I’d promised my dad I’d make sure people knew how talented he was and now here they were, texting in to say they loved his music.”

Still unable to visit her father in person because of Covid restrictions, she had to resort to asking his family liaison worker to play him the song over a video link.

“He was pretty much non-verbal by that point but, when he heard that, he pointed at himself as if to say ‘that’s mine’ and was miming the words,” she says.

“It was an unbelievable moment. He knew I’d kept my promise.”

A few months later, in May 2022 and just after his 90th birthday, Mr Teasdale died.

“I know people hearing his song was his dream come true,” his daughter says.

“But I still had this feeling there was more to do. We’d spoken about maybe one day putting the song into a teddy bear.”

Not knowing where to start, she approached business advisor Brenda Wilson at Project North East who said Little Girl was “so beautiful, I had goosebumps when I heard it”.

Now, two years later, Mrs Teasdale-Robson has her own business and 600 “Teasdale Teddies” to sell which play her father’s song.

Karen Teasdale-Robson

Karen Teasdale-Robson“All I was left when my dad died was the song,” Mrs Teasdale-Robson says. “It’s all I have of him.

“If I can get this business to work, then I want to use the song and my dad’s story to raise awareness of domestic violence towards men.”

She hopes the lullaby could mean as much to complete strangers as it does to her.

“So many people have heard the song, loved it, and then played a part in getting this idea off the ground,” she says.

“I’d never have thought finding that old tape would lead us here.”

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this article, you can access support on BBC Action Line