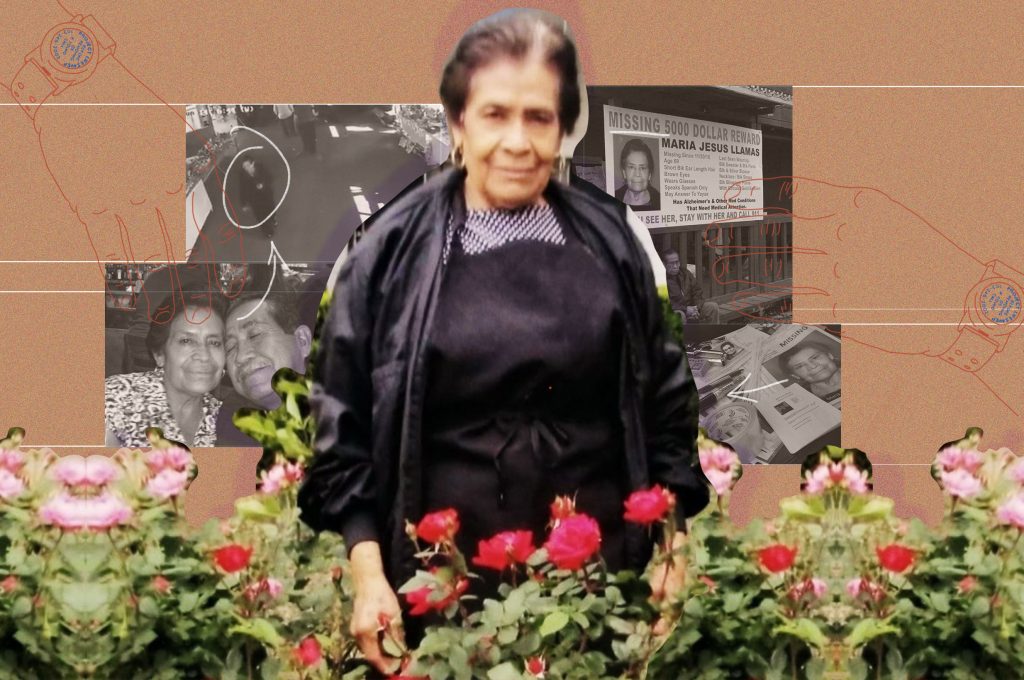

Maria Llamas, 69, wandered away from her husband while shopping at the Poteet Flea Market on a Sunday afternoon in November of 2016.

Hundreds joined Llamas’ husband and four adult children in the search to find her near the flea market, which is 10 miles southwest of San Antonio.

She wasn’t found until almost five years later when hunters discovered human remains at a field nearby that were so bleached from the sun in 2021.

Llamas, who only spoke Spanish, loved going to “la pulga” with her husband every Sunday after the noon mass, then in the evening, everyone would come over for dinner. She enjoyed watching people dance to Norteño and banda music.

Missing in San Antonio is a multi-part series by the San Antonio Report on people who go missing and the people who work to find them.

Read the first story that reveals just how many go missing here.

In the second story here, we share the stories of eight local missing persons cases.

And here’s a guide on what to do if a loved one goes missing.

Share your stories with us through this form.

“Her Alzheimer’s had just progressed so much and so fast,” said her daughter Margie Llamas, 48. “There were a lot of things she forgot, but she knew the lyrics to songs. She could sing an entire song along and know every word.”

Maria Llamas had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease two years before she went missing. She had wandered away from home with a blanket once as her cognitive abilities faded.

Her husband refused to send her to a nursing home. Culturally, it wasn’t an option, Margie Llamas said. So he became her caretaker, helping her brush her hair, do her makeup and make her meals.

Llamas carried a small purse with her with nothing of value inside of it in case she lost it. She didn’t have a smartphone, and at times she told her family she was going to her parents’ home in Zacatecas, Mexico. That’s where she once lived before migrating to San Antonio while seven months pregnant with her third child.

Alzheimer’s disease disproportionately affects Hispanic communities. And researchers say a “tsunami wave” of Alzheimer’s disease is coming as they believe its prevalence will double in the U.S. over the next 20 years. Will our communities be prepared?

Everyday, at least nine people are reported missing in San Antonio. Law enforcement doesn’t track how many of those cases are people with cognitive or neurodegenerative diseases who wander off, but of the city’s 2,770 missing persons cases last year, roughly 5% were for people 60 and older, according to SAPD’s records.

“A majority of our adults, it’s usually elderly people with dementia, or people with schizophrenia,” said Briana Garcia, an agent in SAPD’s Missing Persons Unit during an October interview.

Missing persons advocate and local search sleuth Frank Treviño says seniors with Alzheimer’s who go missing when they get lost is a big issue in San Antonio.

In 2016, he helped search for Maria Llamas with the Heidi Search Center, which closed its doors in 2018 after helping families of missing people for 30 years. The center was opened to honor the memory of 11-year-old Heidi Lynn Seeman, who disappeared from her Northeast San Antonio neighborhood.

In 1990, more than 8,000 volunteers searched for Heidi for 21 days covering 1,200 miles.

Her body was later discovered in Wimberly, 60 miles away from her home.

Treviño recalled that on the same day that Maria Llamas was reported missing, a suspect shot and killed SAPD Detective Benjamin Marconi, launching a citywide search for the killer.

It was mostly volunteers that stepped up to search the area around the flea market.

Several hours had passed and the sun had set when police finally made it to the Llamas home in response to a missing persons report. The family was worried she had asked a stranger for a ride.

According to the San Antonio and South Texas Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association, most people who wander are found within 1.5 miles of where they disappeared. If a person who may have wandered off hasn’t been found within 15 minutes, it’s time to call 9-1-1, the association recommends.

In Bexar County, 13% of people over 65 are currently living with dementia. Just a few hundred miles west, El Paso County has among the highest prevalence rates of Alzheimer’s in the country.

Hispanic populations, especially, have higher risks of developing Alzheimer’s and dementia, according to Dr. Sudha Seshadri, founding director of the Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases at UT Health San Antonio.

Alzheimer’s is a brain disease that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills and eventually interferes with a person’s ability to perform everyday tasks.

“It is easy to get lost and wander away and not find the way back,” said Dr. Neela K. Patel, professor and chief of geriatrics and supportive care in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at UT Health San Antonio.

Patel is also the outreach recruitment and engagement director at the Biggs Institute. When she sees patients older than 85, she tells their children to make sure they have a way of tracking them in case they go missing. She’s encouraged people to buy Apple AirTag devices.

AirTags came out in 2021 and are linked to an app available on iPhones. One can be purchased on Amazon or Walmart and Target for about $23.

Not everyone has the resources, Patel said.

“We need to have a system in place that helps identify them and get them the care and protection they need,” she said.

Doctors have no way of locating patients when they wander away, she said, and there’s no identifying element that would let others know that a person has dementia and is known to wander.

In her 19 years working at UT Health, Patel said two of her patients have wandered away.

One of them, a 90-year-old woman, ended up in Corpus Christi. She was ultimately located by an app on her smartphone that Patel recommended.

Project Lifesaver

The Harris County’s Sheriff’s Office in 2020 partnered with Project Lifesaver International, a nonprofit that partners with municipal public safety agencies to provide them with equipment and training to help locate missing people using radio frequency technology.

The average rescue time for locating a missing individual using this method has been 30 minutes, according to PLI.

Since implementing the program, the Harris County Sheriff’s Office has been able to locate 15 people within 30 minutes from when they wandered off, on average.

The way it works is that a caregiver would notify the sheriff’s office or police department when their loved one went missing. Law enforcement can then use the radio frequency of the bracelet worn by a person to track their location within a seven-mile radius.

In Harris County, a person must have a diagnosis to get on a waitlist for a bracelet, said Sgt. Jose Rico Gomez, the office’s program manager, in an Oct. 24 interview.

Each bracelet costs Harris County between $385 to $400 each, but it’s free for people who qualify for one. Right now, they only have 150 bracelets, which has a battery-operated transmitter which emits a tracking signal.

Gomez says the county was able to fund the program the first year with a $150,000 grant, and paid a director separately with county funds.

Gomez said the agency got another $138,000 grant last year to expand the program so they can use GPS technology on special smartwatches.

New Braunfels and Cibolo police departments also partner with Project Lifesaver to provide devices for its residents with a clinically diagnosed mental disability.

Treviño said such a program could help in San Antonio, where seniors go missing often.

While they’re usually found quickly, in some cases days can pass leaving families longing for answers. Worst case scenario, they’re found deceased, he said.

“There’s a lot of cases that have come up and they go missing three or four times before, eventually, they’re found deceased, but those families would certainly have the peace of mind knowing that they’ve got this tracker on and if they need to find her quickly, they can,” he said.

Apple Watches and similar accessories can help locate seniors, but there’s still the possibility that the person loses the device.

“More counties, more cities, more law enforcement agencies need to know this is happening somewhere. How can we get involved?,” he said.

‘How did we not find her?’

Margie Llamas broke down in tears thinking about the time that passed while searchers focused on the flea market instead of the surrounding area.

She recounted the same story she’d been saying for years.

Refugio Llamas was looking at a booth for a few seconds when his wife walked away. They were heading toward the car, so he walked in that direction, assuming he’d catch up to her. He didn’t see her and started to grow worried.

That evening Margie Llamas took to social media to ask for help and got a tip overnight. A woman whose car had a flat tire in Poteet near the flea market told her she saw Maria Llamas cross traffic on the highway toward them.

“She told them she was on her way to see the muchachos (the kids),” she recalled.

That information helped the family focus the search in a different area, a field only 3,200 feet away from the flea market, where her remains were ultimately found several years later, even though people had searched that area.

The remains weren’t positively identified by forensic investigators until January 2023.

“We don’t want anyone to go through what we’ve been through,” she said.

We are blessed to have found her remains, we’re able to bury them and visit mom and take her flowers. We’re very blessed for that closure, but we still have a lot of questions as to, how did we not find her? How did we not find her then?”