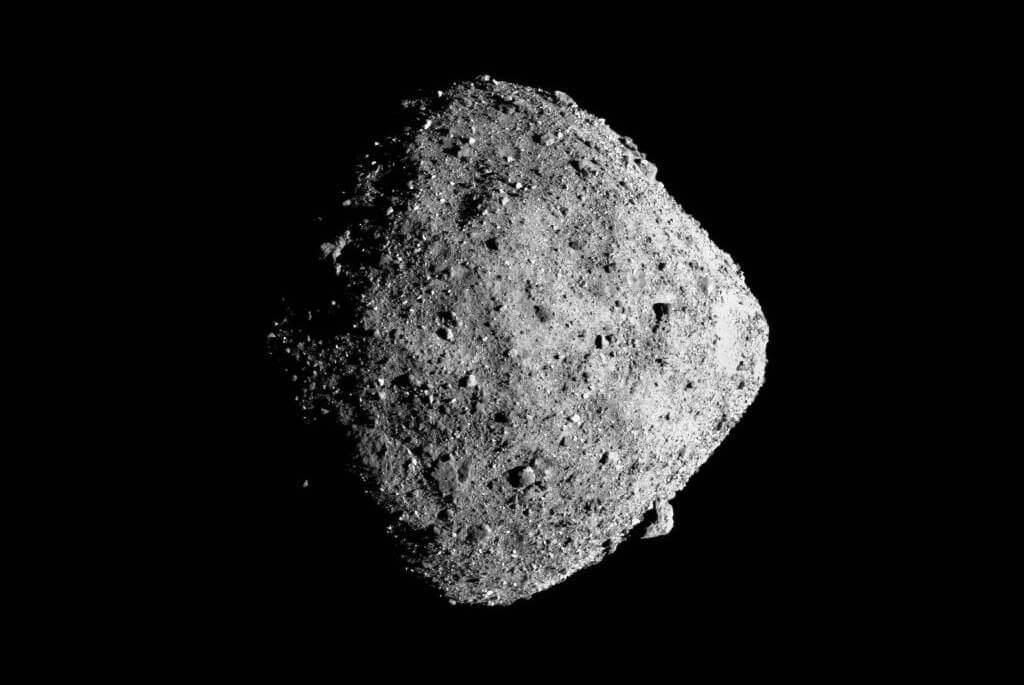

This mosaic image of asteroid Bennu is composed of 12 images taken by the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft from a range of 15 miles. (Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona)

In a nutshell

- Scientists found pristine salt minerals in asteroid Bennu samples that formed in a specific sequence as ancient water evaporated, similar to how Earth’s salt lakes form today

- These delicate space salts, which would normally disintegrate in Earth’s atmosphere, reveal that liquid water was present at surprisingly warm temperatures (20-29°C) in the early solar system

- The discovery suggests similar briny environments might exist today inside icy worlds like Saturn’s moon Enceladus and the dwarf planet Ceres, making them potential candidates in the search for life beyond Earth

WASHINGTON — A pinch of salt has helped unlock mysteries of our solar system’s earliest days. Scientists analyzing pristine samples from asteroid Bennu have discovered an extraordinary sequence of salt minerals that tells the story of liquid water’s role in the early solar system. The discovery could potentially transform our understanding of how life’s essential ingredients were distributed throughout space.

When NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft touched down on asteroid Bennu in 2020, it captured over 122 grams of ancient material, the largest sample ever returned to Earth from beyond the Moon. These samples showed pristine preservation, and were sealed in nitrogen immediately after collection to prevent contamination or degradation from Earth’s atmosphere.

“We were surprised to identify the mineral halite, which is sodium chloride — exactly the same salt that you might put on your chips,” says associate professor Nick Timms from Curtin University, in a statement. This seemingly mundane mineral, along with a variety of other salts discovered in the samples, tells an extraordinary tale of ancient cosmic chemistry.

Salt in the solar system

The story these salts tell begins over 4.5 billion years ago on Bennu’s parent body, a much larger asteroid that was later destroyed in a cosmic collision. As water-rock interactions occurred in this parent body’s interior, various minerals began precipitating out in a specific sequence, much like what happens when a salt lake slowly dries up on Earth.

The sequence began with magnetite (an iron oxide) and sulfides, followed by calcium and magnesium carbonates. As the brine became more concentrated through evaporation, sodium-calcium carbonates appeared, then sodium phosphates, pure sodium carbonates, and finally chloride and fluoride salts. This precise ordering provides a chemical timeline of how water moved and evolved within the ancient asteroid.

“The minerals we found form from evaporation of brines – a bit like salt deposits forming in the salt lakes that we have in Australia and around the world,” Timms explains. “By comparing with mineral sequences from salt lakes on Earth, we can start to envisage what it was like on the parent body of asteroid Bennu, providing insight into ancient cosmic water activity.”

Their analysis, published in Nature, revealed that the brine temperature likely reached between 20-29°C (68-84°F) — surprisingly warm for an asteroid, but ideal for organic chemistry. This temperature range was determined by comparing the mineral sequence to similar deposits in places like California’s Searles Lake, where scientists understand exactly how and when different minerals precipitate out of solution.

What makes this discovery particularly significant is that many of these salts are extremely delicate and would have quickly decomposed if exposed to Earth’s atmosphere. “Being able to examine the same exact atoms using both scanning transmission X-ray microscopy and transmission electron microscopy removed many of the uncertainties in interpreting our data,” says Zack Gainsforth from the UC Berkeley Space Sciences Laboratory. “It took a lot of work to get Bennu to give up its secrets, but we are delighted with the final result.”

Beyond Bennu

Similar briny environments likely exist today inside icy worlds like Saturn’s moon Enceladus and the dwarf planet Ceres, as indicated by sodium carbonate detected in their plumes and on their surfaces. The Bennu samples provide our first direct look at how such extraterrestrial brines evolve and what kinds of chemical environments they create.

From an origins-of-life perspective, the finding is quite intriguing. The combination of liquid water, organic compounds (which were also found in abundance in the Bennu samples), and this variety of dissolved minerals creates precisely the kind of chemical soup that could have helped form life’s building blocks.

“This sort of information provides us with important clues about the processes, environments, and timing that formed the samples,” says Scott Sandford from NASA Ames Research Center. “Understanding these samples is important, since they represent the types of materials that were likely seeded on the surface of the early Earth and may have played a role in the origins and early evolution of life.”

Study author also uncovered an unexpected connection between different parts of our solar system. Some of the material found in Bennu appears to have originated in the coldest regions of the solar system, beyond Saturn’s orbit, before being incorporated into the asteroid. This suggests a much more dynamic mixing of materials in the early solar system than previously thought.

The presence of complex organic molecules, including all five nucleobases used in DNA and RNA, along with these newly discovered salt sequences, suggests that similar chemical processes could be occurring today in the subsurface oceans of icy moons and dwarf planets. “Even though asteroid Bennu has no life,” says Timms, “the question is could other icy bodies harbor life?”

Paper Summary

Methodology

Researchers employed an impressive array of analytical techniques to study the Bennu samples, including scanning electron microscopy, electron microprobe analysis, X-ray diffraction, and transmission electron microscopy. The samples were kept in pristine condition by storing them in nitrogen and analyzing them within specialized facilities designed to prevent contamination.

Results

The analysis revealed a clear sequence of mineral formation, starting with early-formed magnetite and sulfides, progressing through various carbonates, and ending with highly soluble salts like halite and sylvite. The team was able to determine that the brine reached approximately 60-70% evaporation to form these final minerals.

Limitations

While the samples provide unprecedented insights, they represent only a tiny fraction of asteroid Bennu, which itself is just a fragment of its larger parent body. Additionally, some of the most delicate salt minerals began degrading even under careful storage conditions, highlighting the challenges of preserving and studying such sensitive materials.

Discussion and Takeaways

This research demonstrates that complex aqueous chemistry occurred in the early solar system, creating environments potentially suitable for prebiotic chemistry. The findings also suggest that similar chemical processes may be ongoing today in the subsurface oceans of icy worlds.

Funding and Disclosures

The research was supported by NASA and involved collaboration among over 40 institutions worldwide. The authors declared no competing interests.

Publication Information

“An evaporite sequence from ancient brine recorded in Bennu samples” was published in Nature on January 30, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08495-6