Satellites have managed to detect faint electromagnetic signals generated by ocean tides, suggesting that space-born sensors could be used to obtain insights into the motion of other liquid masses on Earth, including magma below the planet’s surface.

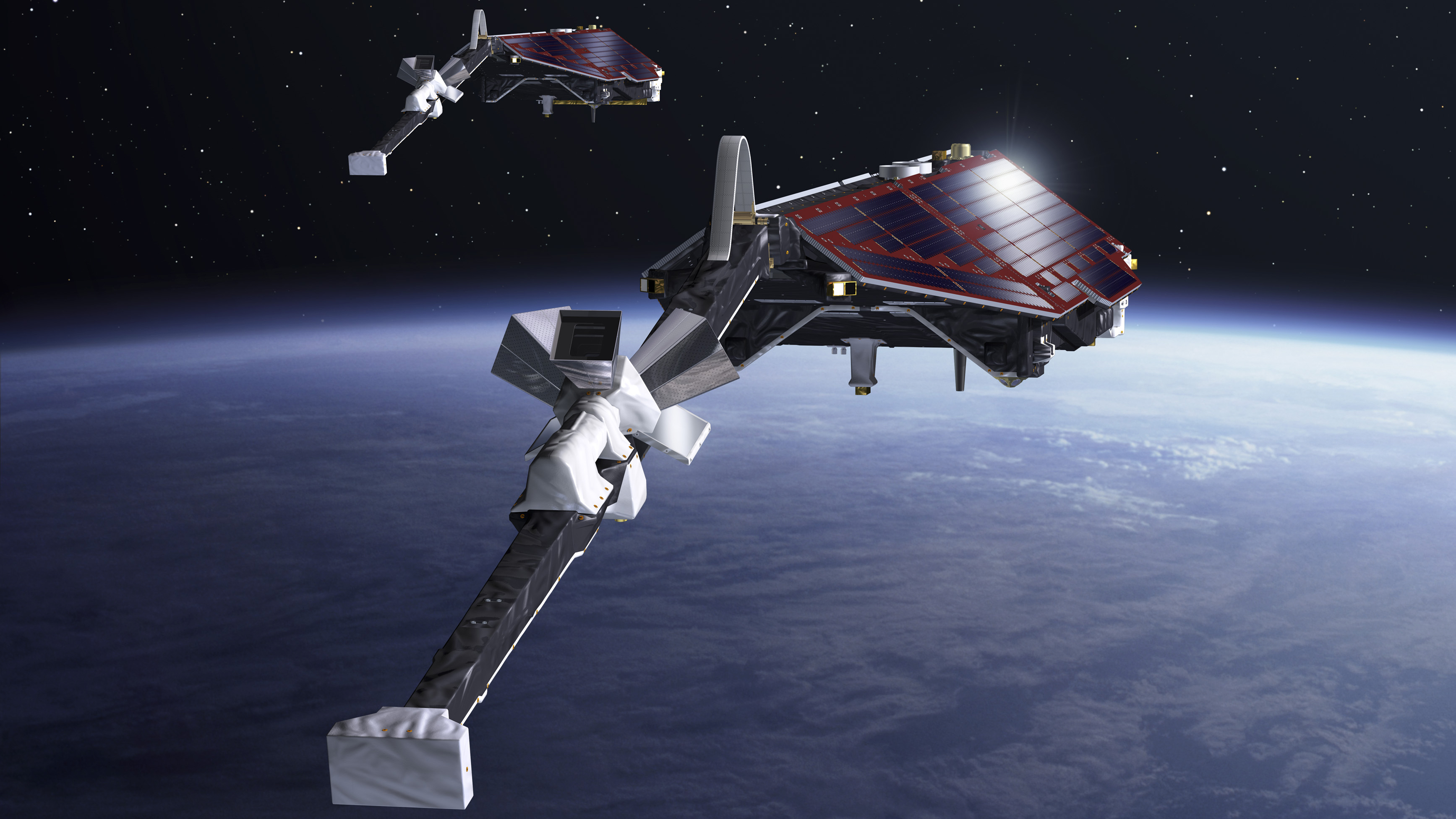

The observations were made by the European Space Agency‘s (ESA) Swarm constellation, which consists of three satellites circling the planet in low Earth orbit at altitudes between 287 and 318 miles (462 to 511 kilometers).

The Swarm satellites, launched in 2013, carry sensitive magnetometers that can spot tiny variations in Earth’s magnetic field caused by the tidal movements of the ocean. Earth’s magnetic field is produced by the motion of molten iron in the planet’s core. It extends tens of thousands of miles into space, shielding the planet from harmful cosmic radiation and bursts of charged particles from the sun.

Since ocean water contains salty ions, it can conduct electricity. As tides push ocean water around the globe, its interaction with the planet’s magnetic field generates a weak electric current. This current in turn produces a weak electromagnetic signal that can be detected from space. Researchers think that by studying variations in this signal, they can learn more about the properties of the water making up the ocean — and possibly also about the magma beneath Earth’s surface.

Related: Why we’re one step closer to understanding how Earth got its oceans (op-ed)

“This study shows that Swarm can provide data on properties of the entire water column of our oceans,” Anja Strømme, ESA’s Swarm Mission Manager, said in a statement.

Scientists think they can deduce information about salinity and temperature changes across the world’s oceans from such measurements. On the magma side of things, they might be able to detect changes that presage powerful volcanic eruptions, such as that of the Polynesian Hunga Tonga volcano in 2022.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Researchers found the tidal magnetic signals in data acquired by the Swarm satellites in 2017. This period corresponded with solar minimum, when the sun produces very few sunspots and solar flares, which energize Earth’s magnetic field. It’s possible that such data collection wouldn’t be possible during a more active part of the solar cycle.

“These are among the smallest signals detected by the Swarm mission so far,” Alexander Grayver, a geophysics researcher at the University of Cologne in Germany, said in the statement. “The data are particularly good because they were gathered during a period of solar minimum, when there was less noise due to space weather.”

The Swarm mission has already passed its expected end of life, but researchers hope the satellites will remain operational until the next solar minimum, which will come at around 2030.

The study was published in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A in December 2024.