The photographer Peter Hujar, admired by friends and fellow artists in Downtown New York of the 1970s and 80s, is lauded by critics today for his portraits of his peers and of animals. Since his death from Aids in 1987, Hujar’s profile has risen enormously. In addition to a landmark show at Raven Row in London (until 6 April), a new film adapted from a transcript of a long conversation with Hujar in 1974, will add to that.

It is December 1974 in New York. A disgraced Richard Nixon fled the White House less than five months before and Nixon’s “Vietnamisation” of the war in Indochina is sputtering.

The world in Peter Hujar’s Day (2025) is a small segment of the art world, but global events figure into the film in mocking references to Allen Ginsberg howling about corporate power, when Hujar (Ben Whishaw) recalls shooting a portrait of the poet. The author of Howl, Hujar says, was not much to look at—or to photograph. “He kept doing ‘om, om om, om om’, and then he sits down in the lotus position, very Buddha, right in the doorway, and he starts to chant,” Hujar says. “I can’t interrupt God. I can’t say, ‘Can you please stop that.’”

The film, directed by Ira Sachs, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival last month. It is a delicate and restrained conversation, mostly a monologue, in which Hujar recounts what happened in the course of an entire day to his friend Linda Rosenkrantz. Their talk was meant to be one in a book of collected accounts from Downtown artists on how they spend their time. The original tape that Rosenkrantz made was lost. A transcript of their talk, found in papers of the Hujar Estate held by the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, was published in 2021.

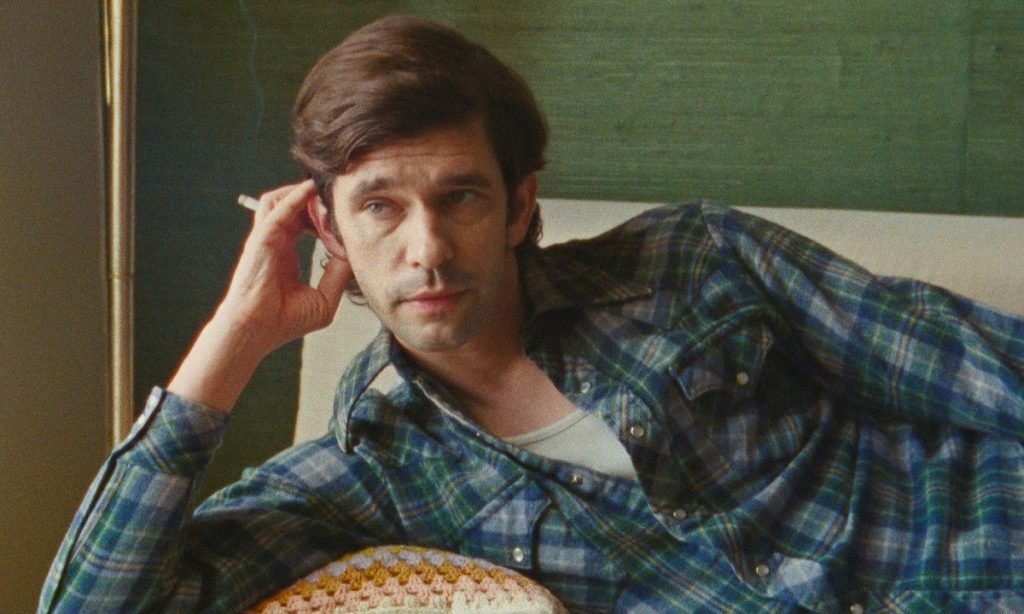

Ben Whishaw as Peter Hujar and Rebecca Hall as Linda Rosenkrantz in Peter Hujar’s Day (2025) Courtesy Sundance Institute

Onscreen, lots of now-familiar names are dropped amid ordinary moments of eating and smoking cigarettes—and an indiscreet secret or two is shared, like Ginsberg’s comment to Hujar that William Burroughs liked preppy young boys. It can feel at times like a pre-Seinfeld ode to an unrecognised artist’s everydayness, in which, as they say, nothing happens.

At the time, Hujar lived in a loft in the East Village, scraping by on freelance assignments. His shoot with Ginsberg for The New York Times was one of those. When Hujar found work, it was ill-paid, but liverwurst and Chinese food were cheap. Cigarettes were ¢56 per pack.

As played by Whishaw, Hujar is a cadaverous journeyman, rich enough in friends and acquaintances, restrained yet jittery about money, since he doesn’t have it. Rebecca Hall, as his interlocutor Rosenkrantz, provides food and advice in a credible Bronx accent.

There is no art on the wall of her apartment in the Greenwich Village artist housing complex Westbeth where the film was shot. Yet Hujar’s way of talking about what he sees reveals a special eye.

After opening their conversation with a fantasy about jumping into bed with a female editor from French Vogue—“I thought it might be terrific right then in the morning, very French”—Hujar, who was gay, recalls photographing the model Lauren Hutton “better than [Richard] Avedon”, who reduced her to a boyish figure in blue jeans.

He tells Rosenkrantz he wants a couch for his loft, so that guests (and intimates) might have a place to sit or recline other than his bed. Yet the bed, where he lies talking to Rosenkrantz, became a crucial prop for him. Some of his most memorable portraits—of Susan Sontag, the dance critic Edwin Denby and various lovers—feature a subject on a bed.

Ben Whishaw as Peter Hujar and Rebecca Hall as Linda Rosenkrantz in Peter Hujar’s Day (2025) Courtesy Sundance Institute

By 1974, Hujar was between anonymity and recognition, already a decade beyond his staggering pictures of skeletons from a crypt in Palermo, clad in clothes that were slower to decompose than their flesh. (His peers who saw those images were floored, but they tended not to get him fashion assignments.) This was also the year of a self-portrait of Hujar leaping into the air, which some may think of when Hujar and Rosenkrantz dance to a country song he plays on her record player.

Sachs’s quiet film has the soft look of a 1970s, 16mm European movie and the feel of a period piece, complete with ever-present smoke and cupboards filled with products from the time. The changing sky in the west evokes Rothko and even Monet’s paintings of Venice, in the case of a blueish tower glowing in the distance. When asked at the film’s premiere about those effects, Sachs said it was all by chance. Plenty of memorable photographs have happened that way.

In the film’s back-and-forth namedropping, there is no mention of Andy Warhol (a marketer of photographs of superstars in art and fashion), Robert Mapplethorpe (obscure at the time, but soon to be a star) or the influential Diane Arbus, who had died by suicide in 1971 at Westbeth. Hujar’s focus here is more narrow, chasing down work but tiring of pursuing boldfaced names. “I’ve always had a star thing,” he says. “I would like my work to stand above that, that my work could stand by itself without a single star in it.”

The understated Peter Hujar’s Day reminds us that Hujar revealed the most about himself—and about so much more—in his pictures. Joel Smith of the Morgan Library & Museum wrote in the catalogue for the 2018 exhibition Peter Hujar: Speed of Life that “the signature move in his art is to lavish a portraitist’s attention upon a subject that defies it”. Smith also quoted Hujar saying: “What I do isn’t any different than what Julia Margaret Cameron did. Or Matthew Brady…I compose the picture in the camera…I make the print. It has to be beautiful.”

And Hujar made that happen. Ira Sachs and his actors expand the growing body of Hujar lore in making a footnote to that trajectory so watchable.

- Peter Hujar’s Day premiered at the Sundance Film Festival on 27 January and screens at the Berlin International Film Festival later this month