The best biennials produce an artistic moment that everyone’s talking about. Often, it’s video that wins the day. Stephanie Comilang makes a convincing case with Search for Life II (2025), a centerpiece of the sixteenth Sharjah Biennial, which opened in February and features two hundred artists in exhibitions sprawling across the city and surrounding areas of Sharjah, in the United Arab Emirates. Comilang’s buoyantly paced video considers the long history of, and present tensions around, pearling, an industry integral to economic life in the Gulf before the advent of oil. The biennial, called To Carry, is about how artists have the endurance to stay underwater, like pearl divers holding their breath, and what happens when they come up for air. They seek beauty, but they also dive for sustenance.

Courtesy the artist; Daniel Faria Gallery, Toronto; and ChertLüdde, Berlin

To Carry is organized by Natasha Ginwala, Amal Khalaf, Zeynep Öz, Alia Swastika, and Megan Tamati-Quennell, curators working in geographies from Turkey to New Zealand whose interests skew towards language, the environment, and cultural heritage. During the opening, Tamati-Quennell amusingly referred to the group as the “Spice Girls,” but little fanfare was made about the fact that a major biennial in the Middle East was directed by five women, and no emphasis placed on who was representing whose territory. Feminism and Indigenous activism are inflection points throughout, but strangely, for an otherwise open-minded exhibition, the word queer doesn’t appear once in the accompanying catalog. Compare this absence to the ludic and sensitive—and openly queer—presentations by the artists Sabelo Mlangeni, Salman Toor, and Louis Fratino, and the pro-trans murals of Aravani Art Project, in the 2024 Venice Biennale.

Yet in Sharjah, the politics of the moment are front and center. When Hoor Al Qasimi, the director of the Sharjah Art Foundation, ended her remarks at the preview, she called for solidarity with the people of Palestine, Lebanon, Armenia, Syria, Congo, and Sudan. Only hours before the official opening, President Donald Trump proposed for the US to “take over” the Gaza Strip, an imperial development scheme tantamount to ethnic cleansing. The idea of solidarity, between regions and across generations, was therefore no mere art-world watchword, but an urgent political stance. The Sharjah Biennial, as Khalaf put it, is “a lament, an offering, a divination ritual” in response to “dispossession and loss.” In other words, survival mode.

Courtesy the artist

Artists working with lens-based media deliver some of the show’s most compelling statements. M’hammed Kilito portrays Morocco’s fragile oases and communal baths, adding a soundtrack of field recordings. The duo Hylozoic/Desires (Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser) used the AI image generator Midjourney to make gold-toned, nineteenth-century-style salt prints that envision a four-thousand-kilometer hedge built by the British in India to evade a salt tax. Mónica de Miranda stages dramatic scenes amid abandoned buildings in the Namib desert in Angola, where solitary figures emerge as surveyors of a postcolonial utopia or witnesses to an end-times scenario. It’s a vision that’s materialized in another dispensation by the sculptor Hugh Hayden, who places Brier Patch (2022), a collection of wooden school desks sprouting tree trunks, in an abandoned desert village that doubles as a biennial site.

In Search for Life II, Comilang deftly blends the styles of the nature documentary and the music video, using several cameras to tell a story about commerce and migration. Golden-hour cityscapes of Dubai, shot from the Burj Khalifa, complement lush underwater visuals. A cameo by Fatima Khalid, also known as Pats, a Filipina Emirati who performs with a K-pop cover group called the Pixies, provides a charismatic counterpoint to scenes of an open-air pearl market in Zhuji City, China. Comilang projects one channel of the video onto an enormous screen made from strings of acrylic pearls sourced from a factory near Shanghai. She built a pier from which visitors could view the video on multiple levels.

Courtesy Sharjah Art Foundation

A second channel, on an LED screen, shows dancers from the Pixies and TikTok videos of jewelry designers. “Pearls,” a text message reads, “are the new diamonds.” Filipinos constitute one of the major migrant groups to the United Arab Emirates, yet children born there to foreigners are rarely seen as fully Emirati. Pats speaks with uncommon candor about her mixed-race identity, appearing as an avatar of a hybrid Emeriti future. Elsewhere in Comliang’s film, the family of a Filipino diver who was paralyzed after coming up for air too quickly returns a pearl to the ocean in a ritual offering. The pearl will have more value in the spirit world than the open market.

Search for Life II is presented in Al Mureujah Square in Sharjah City, a labyrinthine collection of galleries that forms the principal venue of the Sharjah Art Foundation. In a sleek white cube, Kapulani Landgraf shows selections from Nā Wahi Kapu o Maui, a series of black-and-white photographs of sacred sites in Hawaii. The pristine quality of her prints, and the long exposure times that render the movement of water like ripples of satin, are comparable to mid-twentieth-century landscapes by Ansel Adams, who also photographed in Hawaii. But Landgraf, who is native Kānaka Maoli, includes texts below each image denoting place-names related to Indigenous Hawaiian genealogy. For Landgraf, the sublime is not about manifest destiny, but instead the continuity of cultural knowledge.

Courtesy Sharjah Art Foundation

In the Bait Habib Al Yousef, an historic courtyard house renovated by the foundation, a group of photographs by Akinbode Akinbiyi contemplates the choreography of spectatorship. His images of street life, photo studios, and everyday rituals in a variety of African cities contain the subtlest vibrations of forward motion. “He listens with his camera,” the curator Natasha Ginwala said. Akinbiyi’s prints are organized in elegant grids or set at various heights within concrete recesses, spot-lit and self-possessed. One image shows two men pointing handheld video cameras toward a couple in the middle of an outdoor wedding ceremony. Like the pair of documentarians he portrays, Akinbiyi himself is a photographer-participant, close enough for an intimate encounter yet standing at the slightest remove to sense a moment of visual poetry.

Courtesy the artist

Among other sites repurposed by the Sharjah Art Foundation is the Old Al Jubail Vegetable Market, a gently curving arcade that serves as a stage set for Aziz Hazara’s ingenious, multifaceted project I Love Bagram (ILB) (2025). Bagram was an American military base and prison until the summer of 2021, when the US withdrew its troops, switched off the electricity, and essentially vacated overnight. Hazara began to collect garbage left at the base, photographing ghostly bottles of mouthwash, lotion, and conditioner and installing his pictures in typologies set against the brightly patterned wallpaper of former fruit and vegetable stalls, a post-occupation bazaar within a post-commodity market. He added videos of Afghan men handling electronic waste, allowing power cords for projectors to pile up unconcealed, as if to say that even these exhibition devices will end up in some other market someday.

The afterlife of an ancestor, or the afterimage of a photograph, is the subject of several of the biennial’s projects about art as a container for history. Like Hazara, Alia Farid delves into the recent record of US military intervention abroad. She researched objects taken from Iraq after the American-led invasion in 2003, and became fascinated by blue faience, a ceramic material used in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. For her series Talismans, she embedded photographs, enlarged on a copier, of her mother and her grandmothers, who were from Puerto Rico and Kuwait, within polyurethane panels. Glazed with blue faience, the panels are suspended from the ceiling, inviting a continual movement around the gallery to glimpse the images in their various layers, like peering through a window.

Courtesy Sharjah Art Foundation

Courtesy the artist and Starkwhite Gallery, Auckland

Fiona Pardington photographed life casts made in the late 1830s by a French phrenologist in New Zealand. Depicting Maori leaders who are also ancestors of Pardington and the curator Megan Tamati-Quennell, the casts are what Pardington calls a “pre-photographic form of portraiture.” She printed her arresting, evenly lit images at a large scale, pointing up the monumentality of the figures and their uncanny lifelike presence. They appear neither as exemplars of nineteenth-century pseudoscience nor as idealized heroes, but instead as individuals hovering between life and death. “We have our family with us once again,” Tamati-Quennell said.

Collection of Kegham Djeghalian Jr. and courtesy the artist

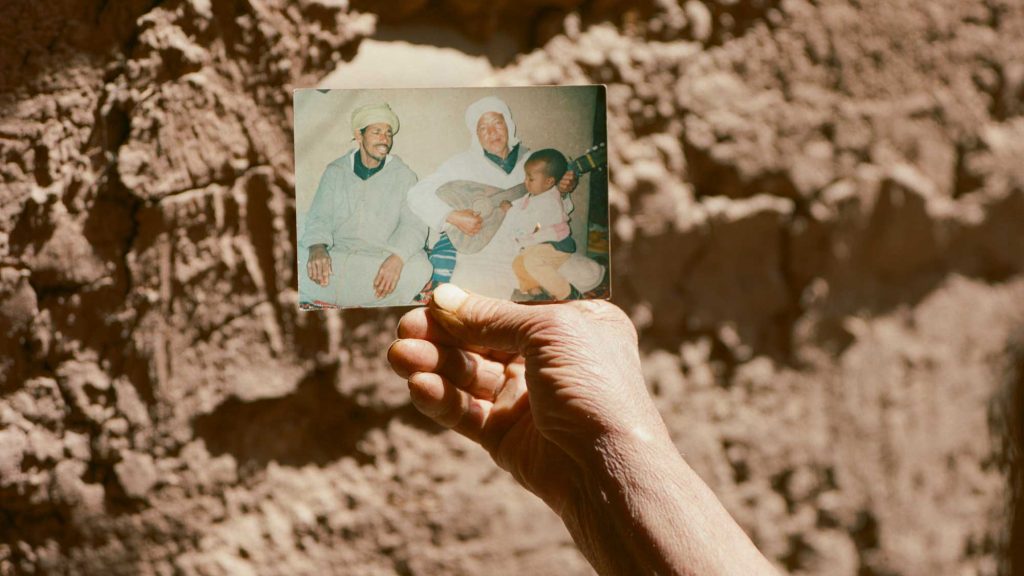

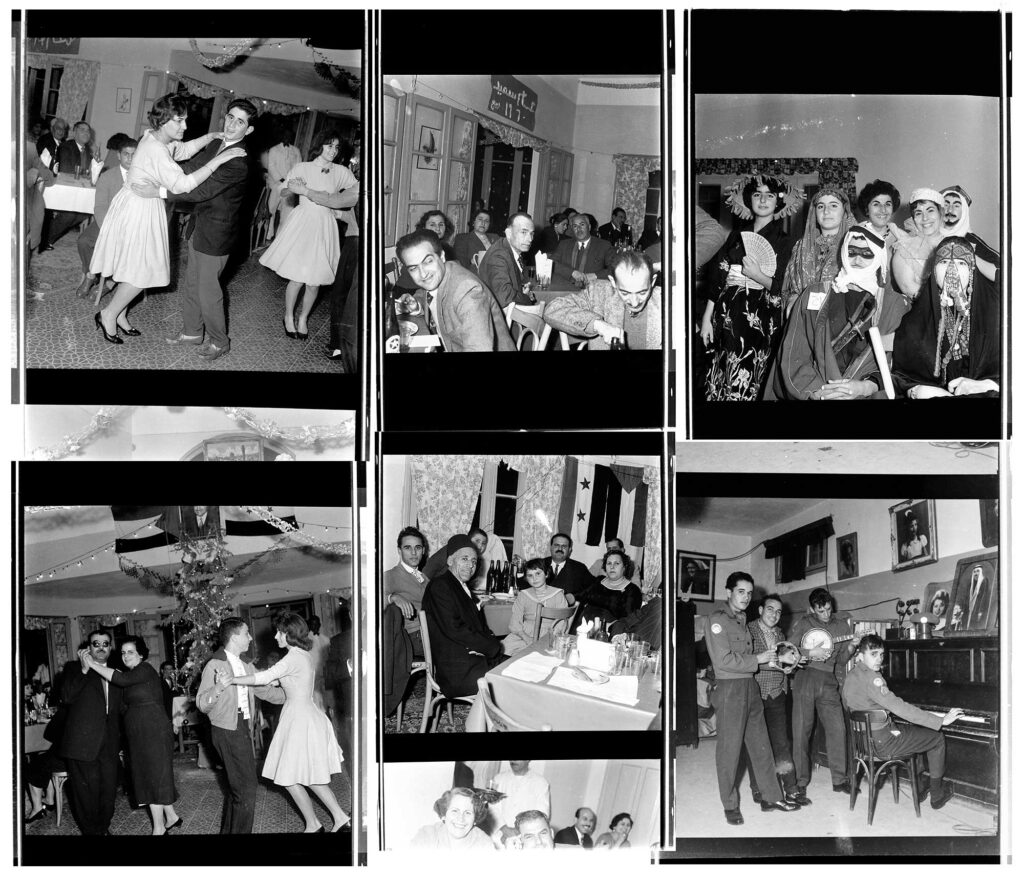

In 1944, Kegham Djeghalian, a survivor of the Armenian genocide, opened the first professional photo studio in Gaza. Decades later, his grandson, Kegham Djeghalian Jr, an artist based in Cairo, began to investigate the studio’s legacy: three red boxes of prints and negatives showing the rhythms of daily life—weddings, parties, street scenes, family portraits—that also amount to a community’s proof of existence. In a gallery at the Sharjah Art Museum, Djeghalian Jr presents hundreds of black-and-white reproductions from the studio’s archive, withholding individual dates or locations, a gesture that suspends the images in the present tense. He recreated the Photo Kegham storefront in a Sharjah souk, and he screens a video interview from 2021 with Marwan Al-Tarazi, who inherited the studio. Together they discuss the photographs in detail, but the video would be a final encounter. Al-Tarazi was killed during an Israeli bombing in Gaza in October 2023.

When it’s time to “travel, flee or move on,” the biennial’s curators ask, what do we carry for survival? For the Palestinian artists Mohammed Al-Hawajri and Dina Mattar, who are part of Eltiqa, an artist collective in Gaza City, endurance is about cultural protection. Al-Hawajri and Mattar were living with their family in a Rafah camp when they decided to flee Gaza, carrying with them as many artworks as possible. In a former classroom at the Al Qasimiyah School, a 1970s-era building that serves as another of the biennial’s sites, they present political paintings that channel Diego Rivera and Faith Ringgold, together with artworks by their children, including a video by their eldest son, Ahmad, who follows the path of a kite flying over a refugee camp in Gaza. Al-Hawajri and Mattar’s work is also featured in a concurrent exhibition about Eltiqa at the Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai, in which a timeline of photographs tracks the activities of the collective from its founding in 1988 to the ceasefire in January. Like the portraits from Photo Kegham, the images of joyful exhibition openings at Eltiqa’s gallery in Gaza are an intimate form of evidence.

Courtesy Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai

At the biennial preview, the curator Alia Swastika introduced Al-Hawajri, Mattar, and their four children in the courtyard of the Al Qasimiyah School, just outside the gallery where their artworks were on display—artworks they had risked their lives to salvage and bring to the Emirates, or have made since arriving. They lined themselves up in order of height and the children listened as Al-Hawajri spoke about the exhibition. The moment was like any other artist talk at the biennial, but the family’s presence was overwhelming. They had survived.

To Carry, the Sharjah Biennial 16, is on view in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, through June 15, 2025.