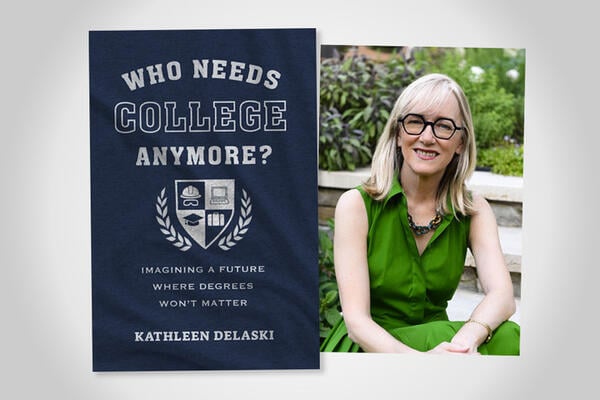

In her eloquent new book, Who Needs College Anymore? Imagining a Future Where Degrees Won’t Matter (Harvard Education Press), Kathleen deLaski, a former journalist who founded the Education Design Lab to help colleges develop alternative pathways for learners to achieve their goals, traces the history of the skills-based education movement and outlines a compelling vision for a future where hiring and economic success are driven by skills—not degrees. DeLaski, who also teaches at George Mason University and serves on the board of Credential Engine, a nonprofit seeking to create standards and clarity for alternative credentials, spoke with Inside Higher Ed via Zoom.

Excerpts of the conversation follow, edited for length and clarity.

Q: Your book seems to start from the premise that the main purpose of postsecondary education is to get a job. But what about the less tangible soft skills—what you call “durable skills”—such as critical thinking and the other things the liberal arts are credited with imparting? Are those less important now or can they be acquired in other ways?

A: I think durable skills are as important as ever, if not more important. That’s certainly what surveys suggest, and employers say they care about them. But I would argue that consumers don’t see the value proposition when they look at their four-year degree gauntlet … They are not tangible enough or packaged in a way that a student can put durable skills on their résumé and have themselves be differentiated to an employer that might care about collaboration or critical thinking or creative problem-solving.

One of the main points of the book is that college is losing its reputation, if you will, because of two big things. One is the perception of affordability, and the second is a view that what they might learn in a four-year degree is not relative enough to getting hired and getting into the workplace. And those two are highly related.

I started the book talking about my great-grandfather times seven, John Wise, who was an early Harvard graduate in 1673, and at that time, Harvard was only training ministers. What hit me was that his expectation about what he was going to do in college was highly correlated with what he was going to do for his job as a minister. That was where the degree model originated. As technology developed in the 20th century, what you might ostensibly need to get on the hiring ladder versus what you learned in college started to diverge. And I think that’s also the time at which this attitude of “Is college worth it?” started to emerge.

Q: A lot of the people you talk to in the book—and I think you would put yourself in this category—used to be in the “college for all” camp but have had a radical rethinking of that approach. What drove the shift?

A: Part of it was the time, and part of it was the data that we started to get. I was in the charter school movement in the 2000s and early 2010s, and we were all very inspired by this idea that if we could create more quality seats for K-12 in urban schools, we could double the number of low-income learners who would go on to and succeed in college. There was quite a bit of success in opening the aperture of college to more low-income learners from districts where they were not well prepared. But when we started to get the statistics about how they were doing, students of color, low-income students—something like 50 percent of those learners were not making it through university.

I still am very pro degree, but I feel like I’ve met so many people for whom it didn’t work that I am in the camp now where I want other pathways to help people get to the same level of economic success. We need additional pathways for different kinds of learners, for people who are in a hurry for whatever reason to get where they want to go, who have the kind of job aspirations where hands-on makes more sense, and for people who don’t have the support systems and might have childcare responsibilities, or like one of my daughters, who’s neurodivergent.

Q: You note that the federal government provides much more financial assistance for college than for alternative forms of education or training. Do you have any hope that will change under the new Trump administration?

A: I believe that when the dust settles, there will be support by the Trump administration for short-term Pell–type funding streams that help. Probably dollars coming through states to help workforce training programs—as long as they strike all the DEI language.

Q: One of the challenges with the microcredential movement is that there’s very little oversight to ensure quality or consistency. How can that be addressed so that when somebody has a particular certificate or badge or whatever, an employer knows exactly what it means?

A: The reason they’re not evaluated, at least when colleges are involved, is because historically, they haven’t qualified for federal financial aid, and so there are no requirements to evaluate them. And often they were spun up quickly to address a particular industry demand so they’re often on the noncredit side of a college. That’s why microcredentials feel like the Wild West.

That is changing on the college side; Design Lab is working with 100 community colleges on micropathways, which are a set of two or three microcredentials. And we are asking all of the colleges to get into a data collaborative with us, and that’s beginning to take hold. You’ve got nonprofits forming to bring evaluation to the field. And then Credential Engine, I think, is doing a good job of the naming conventions and, helping to figure out, if you’re going to offer a microcredential, what are the data points you should feel compelled to offer in order for people to understand the quality of it?

Q: You talk about the concept of creating skills wallets for students that reflect the competencies and credentials they’ve acquired. How does that work?

A: Well, it’s starting to roll out in a couple of states. Alabama’s probably one of the best examples where employers and schools are coming together to both set up naming conventions around skills and starting to provide a wallet, which is basically a next-generation learner employment record. It’s like a transcript, but you start getting it in high school and what’s fed in is organized by skills rather than by classes. In its best life, it’s a skills transcript that would follow you throughout your school career and into your different jobs.

If you fast-forward 10 years and look at what the promise of a skills wallet could be, it includes an interactive feature where it can, assuming you trust it, be your sort of Hollywood agent, or AI-infused job adviser. It can help show you different possibilities of what jobs you might qualify for, but also provide your skills adjacencies to show you what’s the distance from this job to that job. I liken it to a Google GPS navigator and describe that as the point we need to get to for the real possibilities of skills-based hiring and learning to take hold.

Q: It seems like one of the biggest obstacles to this future might be faculty, who tend to be more interested in imparting their subject expertise than in necessarily teaching concrete, marketable skills. How can you get faculty on board with skills-based hiring?

A: It’s really hard. I struggle to drink my own Kool-Aid when I teach. I try to list my course outcomes by skills. But I did a survey this fall at the end of my course and asked my students, “Do you feel like you have this skill now? Which of these skills would you put on your résumé?” And I would say I got a B-minus. My students didn’t feel like they’d gotten there. Part of it is I teach design thinking and higher ed redesign—more liberal arts, general education kinds of courses that are hard to skillify. So I’m sympathetic with faculty, but I also want to be diligent that we have to have data points of what the skills are, and employers have to help us in higher ed get there.

Q: So can you answer the question you pose in your title? Who does need college anymore?

A: Ten years ago, I would have said everyone. At this point, the group of people who can afford to skip college include connected career switchers, of which my daughter was one. There are motivated DIYers, who just are good at figuring out how to get things done on their own, and they’re not hankering to be in a group setting for four years. I also include people who can find a pre-packaged career route, and that’s really where apprenticeships come in. And then the last category is what I call undecided, maybe-laters—people who just don’t know what they want to do. They might wander into college and take a class or two, and that’s fine. But there may be better options for them.

And the groups for whom college remains by far the best option would include what I call class transporters, or people who maybe come from immigrant families, who are trying to find their foothold, and they need the social networking, they need to learn what the careers are, and if they can find a low-cost option, that’s going to be best. The second group is what I call legitimacy label seekers: people who just want that piece of paper, for the sake of confidence or sort of like a self-fulfillment piece. And then the biggest category are people who want to be in careers where a college degree is just absolutely required. The numbers of those careers are shrinking, but there’s some that will probably require a degree for a long time. I call them license to workers, which includes doctors, lawyers, nurses and teachers.

Q: Do you think the momentum for skills-based education is unstoppable and that it’s just a question of how and when we get there?

A: I would have thought so as we were coming out of the pandemic. That felt like another blow to the trend lines that we were already seeing. But I am encouraged by the increase this past fall in freshman enrollment. The growth suggests that consumers are still looking to colleges to figure out their employment path solutions. But you know, a growing number of them are looking for a different model. And so when colleges say, “Well, what should we do?” my No. 1 suggestion is … that college needs to be designed as a stepladder approach, where people can come in and out of it as they need, and at the very least, they can build earnings power along the way to help afford a degree program.