A debate about the age of Saturn’s resplendent rings has been raging for a few decades now, with no end in sight. A new study by researchers at the Institute of Science Tokyo and the Paris Institute of Planetary Physics has fresh spin to offer now that could recast the conversation.

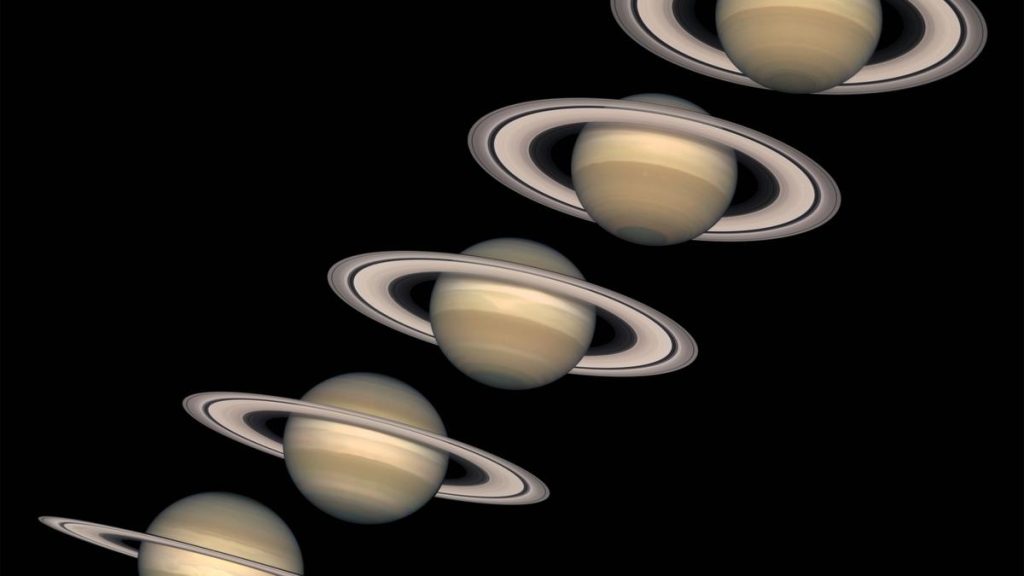

Saturn’s rings are an arresting sight even through modest telescopes. The planet is made mostly of hydrogen and helium whereas the rings are billions of pieces of mostly bright-white water ice and rock. Some of these pieces are as small as a grain of salt; others are as big as a house.

Four spacecraft have visited Saturn thus far, all launched by NASA: Pioneer 11 and the twin Voyagers 1 and 2 flew by it while Cassini orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017.

Unusually clean

Cassini in particular found the rings to be squeaky clean, with very little dirt. This is unusual because everything in the Solar System, including the earth, is constantly bombarded by dark pieces of dust, each finer than a grain of sand. These particles are fragments of larger chunks of rock in space.

Most of this debris burns up in the earth’s atmosphere when they get too close and never reach the surface.

Around Saturn, astronomers expected this dark dust to be omnipresent in the rings, but this isn’t the case.

Based on this, scientists hypothesised that Saturn’s rings are relatively new, only around 100 million years old — too young to have accumulated the dust.

This was a simple explanation, which is good, but there is a catch: scientists don’t know how the rings could have formed so recently.

Rings out of time

In these last 100 million years, the Solar System has been pretty calm.

“In the very early stages of the formation of our solar system, around four billion years ago, the system was chaotic and unstable,” Ryuki Hyodo, from the Institute of Science Tokyo, Chief Science Officer at Tokyo-based company SpaceData Inc., and a coauthor of the new study, said. “Therefore there is a greater chance of a big, dynamical event happening then that could form Saturn’s rings.”

“Crater size distribution is used to constrain the age of solid bodies in the solar system,” Sean Hsu, a research scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder who wasn’t involved in the new study, added. “For Saturn’s rings, age determination is even more difficult — there are no craters, and the collisional nature of ring particles erases most of its history. Depending on which measurements you choose, it is not too surprising that people end up with very different age estimates.”

“In my view, the ‘blind men and an elephant’ is not a bad metaphor here.”

Keep ‘em out

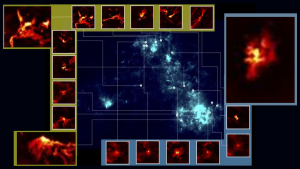

In the new analysis, Hyodo’s computer models showed that when dust particles collided with ice in Saturn’s rings, they evaporated and dispersed into hundreds of even smaller flecks, which Cassini had also observed.

The models showed that these particles then smash into Saturn itself, beat the planet’s gravitational pull or are dragged into the planet’s raging atmosphere. In other words, the pearly shine of Saturn’s rings is not thanks to them being young but because they have a way to eject such foreign bodies that enter their delicate world. In sum, there’s no reason for older rings to be darker (or vice versa).

In fact, the rings could be as old as the Solar System, according to Hyodo.

“The basic assumption in the debate about the age of the Saturnian rings centres around the water ice composition of the ring particles,” Wing-Huen Ip, who studies the origins of the Solar System and the formation of planets at the National Central University, Taiwan, and who was not a part of the new study, said. “We actually can’t be 100% sure that this is true.”

“Such an estimate is indeed questionable, because we do not know what the ring composition was when it formed,” Hsu said.

The new findings were published in the journal Nature Geoscience in December 2024.

Europa, Enceladus, and beyond

Determining when Saturn got its signature rings isn’t just a matter of curiosity. “The interest in probing the age of Saturn’s rings is beyond the rings themselves — it is about the implications, and there are many,” Hsu said. “Enceladus, the geologically active moon of Saturn, is a top-priority target to study habitability and astrobiology due to active plume activity from its subsurface ocean. The evolution of Saturn’s rings has fundamental impacts on the evolution of Enceladus, and other icy moons of Saturn, as they’re dynamically coupled.”

In the mid-2000s, Cassini found plumes abundant in water molecules leaking from Enceladus’s southern hemisphere. It also recorded evidence of cryovolcanoes, icy promontories spewing hydrogen, salt crystals, water vapour and ice, and volatile compounds like ammonia. The vapour condenses into solid flakes, not unlike snow on the earth, and drifts into one of Saturn’s rings.

In 2014, NASA scientists reported finding evidence of a 10-km-thick ocean of liquid water under Enceladus’s south pole region in Cassini data. Ip believes investigating how icy grains from the plumes of Enceladus affect the ring’s composition could play a major role in determining the ring’s age.

In related news, NASA launched the Clipper mission to study Jupiter’s moon Europa, which is similarly dynamically linked to Jupiter and contains a subsurface ocean as well, in October 2024.

The new study could also help explain why the Solar System’s four gas giants have such diverse ring systems. Either they were different by birth or diverged as they grew. The dynamics unveiled in the study could infuse fresh insight into this debate.

“We may propose to send a spacecraft to Saturn’s rings to study them in more detail,” Hyodo said.

Unnati Ashar is a freelance science journalist.

Published – February 19, 2025 05:30 am IST