Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This article was co-published with the New Jersey Monitor.

Rachel Hodge worked as a housekeeper at a hospital and was earning an online degree in social work when schools shut their doors due to COVID. Spending hours in front of a laptop with a 5-year-old just didn’t fit into the picture.

But in the fall of 2020, her daughter Vanessa was set to start kindergarten at KIPP Upper Roseville Academy in Newark, New Jersey. With Hodge working and school still remote, Vanessa spent her days with a babysitter, who cared for multiple kids and struggled to manage the technology for virtual learning.

By November, Vanessa was one of 24 kindergartners in Newark’s KIPP charter network listed as missing from remote school.

That’s when KIPP staff created the Evening Learning Program, a condensed school day that accommodated parents’ upended schedules. The program, which ran weeknights from 5:30 to 8 p.m, remained in place until the end of the school year.

“It was really a sad and scary time,” Hodge said. “But I was like, ‘The kid’s got to learn.’ ”

As Hodge worked on her own assignments from Rutgers University, kindergarten teacher Meredith Eger led Vanessa and classmates in songs and games, and through the reading and math they’d missed since August.

“It was fun and it was kind of weird,” Vanessa, now 9, recalls. “When class was over, I didn’t have to pack up, because all my stuff was at home.”

The program is a rare example of a school that moved quickly to keep children from missing out on their first year of school — a critical transition period in which they typically start developing academic and social skills. At a time when hundreds of thousands of parents struggled to balance work and Zoom, or held their children out of school until first grade, KIPP’s after-hours program offered families some consistency in the midst of turmoil.

But nationally, many students who missed out on a normal kindergarten are still feeling the lingering effects of that lost year. Research released this month documented how the pandemic’s youngest learners experienced significant declines in general knowledge, cognitive development, and language and social skills compared with their peers before COVID. Academically, these students are still performing below pre-pandemic math and reading levels.

Five years later, Vanessa is one of 11 night-school kindergartners who still attends KIPP Newark schools. She “writes up a storm,” Eger said, and often draws during lunch. Others prefer math. Parents notice their kids sometimes keep to themselves at home — a preference they blame on a shortage of playtime with peers during lockdowns. The educators who ran the program, which served students up to third grade, enjoy a special bond with the kids they nurtured through that trying period, grabbing hugs in the hallway or cafeteria when they can.

“They were falling drastically behind,” said Rebecca Fletcher, the charter network’s director of school operations. “It was a bright spot in such a dark time.”

‘They weren’t coming to school’

Thomas Dee, an education professor at Stanford University who tracked the sharp decline in kindergarten enrollment during school closures, called KIPP’s night school “a creative way to meet the needs of parents during the crisis and one that wasn’t common in traditional public schools.” Such flexibility may have also kept families from pursuing options, like pods or private schools that were in-person, he said.

KIPP leaders didn’t compare the performance of the evening kindergartners to students who logged in during the day, making it difficult to measure student outcomes. But the program was born of necessity, Fletcher said: The abbreviated school day was better than no kindergarten at all.

“They weren’t coming to school,” she said. “It was about meeting families where they were.”

Parents turned to night kindergarten for a variety of reasons.

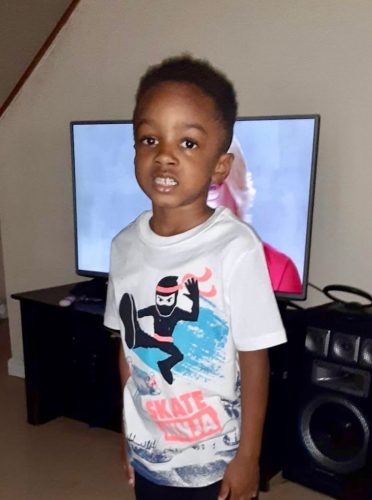

Nateesha St. Claire had just had her third child and couldn’t juggle an infant daughter and online school for Omari, her kindergartner.

“At night, there were really no distractions,” she said. The baby was asleep. But it was still a struggle to keep Omari focused on his teacher. If St. Claire didn’t sit close, he’d walk away from the screen. He frequently asked why he couldn’t go to school.

Now in fourth grade, Omari is “thriving” in math, growing in reading and getting help in speech class to pronounce words more clearly, his mother said.

‘A labor of love’

One advantage of the evening sessions were smaller classes, which allowed staff to identify students who had learning delays or qualified for special education services. Such needs might have gone undetected in a larger online group, said Kaneshia Clifford, who was principal of the program.

Two children were on the autism spectrum and others, she said, were nonverbal or “mildly verbal.” She recruited special education teachers to the team who broke lessons down into smaller segments and organized separate Zoom groups for more targeted support. But keeping the kids’ attention while trying to assess their skills proved daunting. Teacher Adrienne Rodriguez Liriano rewarded students who focused on lessons by putting her dog Harlem on her lap in front of the camera.

“Teachers had to keep a lot of things on their brain,” said Clifford, who had her own kindergartner at home at the time. “They’re looking at screens, asking kids to hold up white boards. They’re trying to monitor engagement in a virtual space, while also collecting data.”

And that was after a full school day of teaching online and sometimes delivering laptops and hotspots to students’ homes. Fletcher described the schedule as “grueling,” but also “a labor of love and devotion.”

Because of the late hour, some students showed up on Zoom with wet hair and wearing pajamas. Others ate dinner during class. Some nodded off.

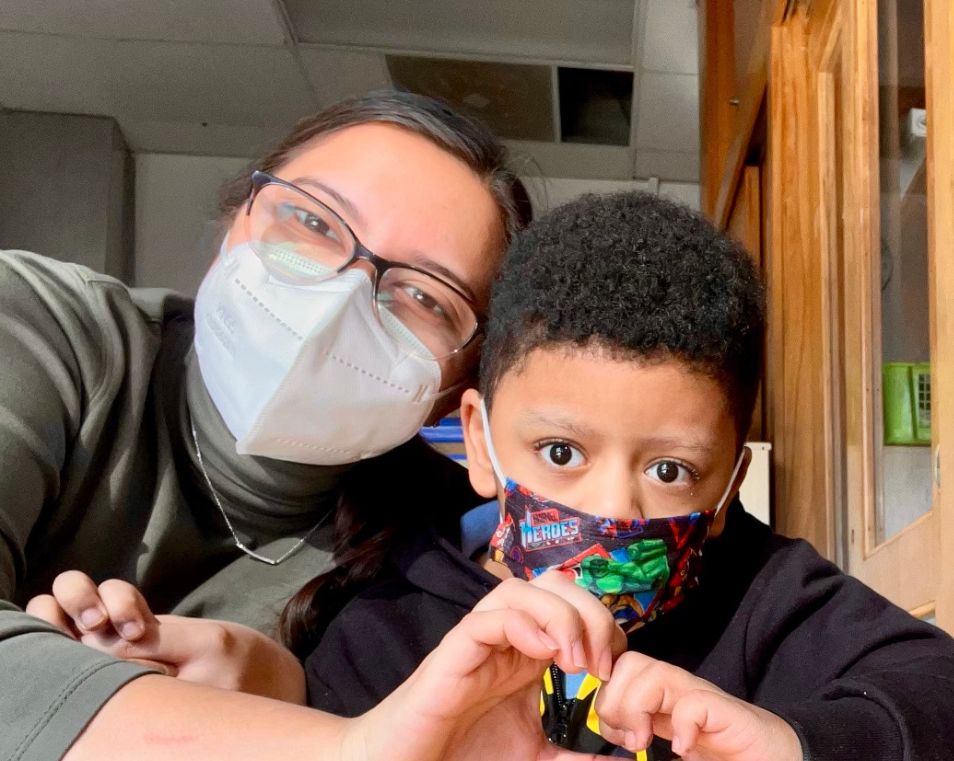

Beatriz Warren, who worked during the day as a home health aide in New York City, welcomed the evening option, which allowed her to attend to her son Josiah.

“It’s a mom thing, I guess,” she said.

Ear infections and surgeries caused Josiah’s learning to be delayed. He received therapy at home before the pandemic, but as kindergarten approached, Warren worried about whether to put him in a general or special education class. Night kindergarten offered a welcome mix of individualized support and as-close-to-normal a classroom experience as possible.

“He bonded with the kids and the teachers,” she said. And when schools reopened, Warren enrolled him in KIPP Upper Roseville Academy, where Liriano, his teacher, worked — even though it was a half hour away. Liriano now teaches outside of the KIPP network, but still Facetimes with Josiah and his mom.

“He asks about my daughter,” Liriano said. “We became invested in each other’s lives because of the environment we set for them.”

‘He lost a year’

With their children nearing the end of elementary school, parents continue to see the ripple effects of a year without in-person learning.

Josiah has overcome most learning delays and “does not stop talking,” his mother said. But he often spends time alone rather than playing with friends or toys. And Hodge described Vanessa as a “hermit” who often retreats to her room.

“The kids were so young, they were conditioned to be inside because of COVID,” Hodge said. “I feel like a lot of the kids still are behind socially … because they couldn’t have normal interactions.”

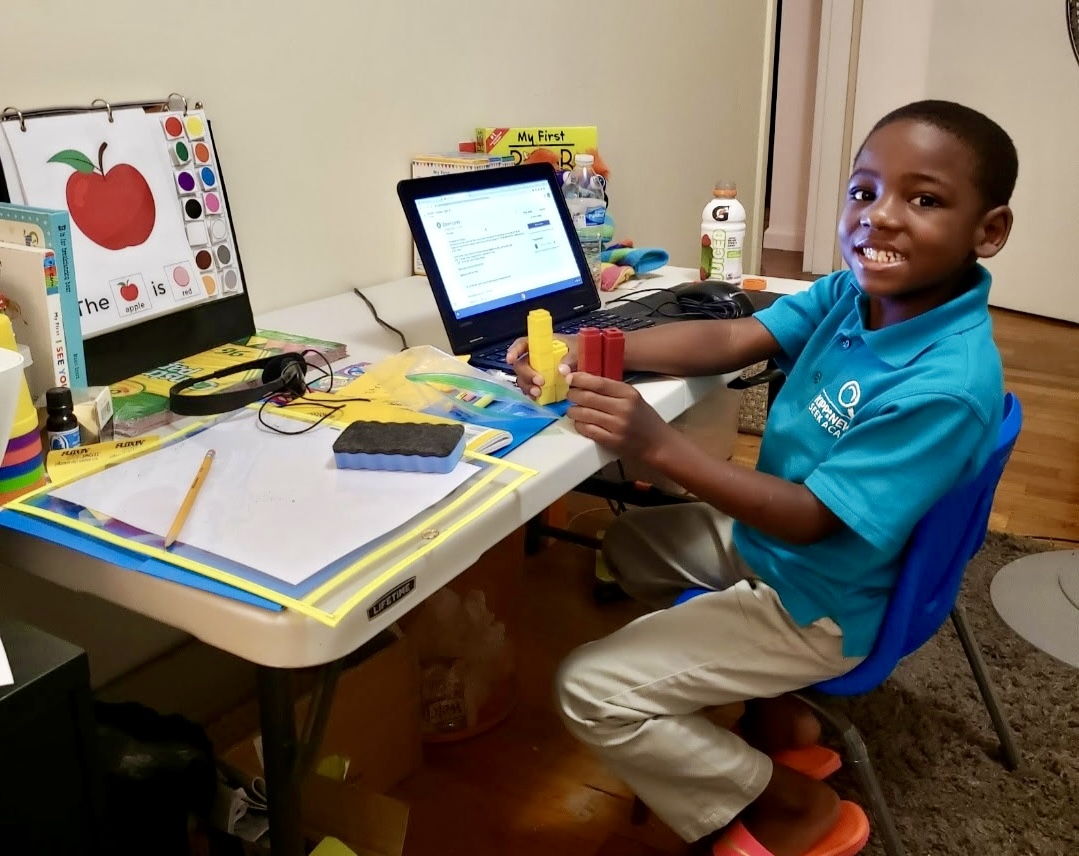

Aminah Cooley’s grandson Ayden, also part of the evening kindergarten program, didn’t hold a pencil correctly until nearly second grade, she said.

“They were looking at the screen. A lot of times, they weren’t using a pencil,” she said. Now a fourth grader, Ayden loves math and enjoys the popular Dog Man series of graphic novels by Dav Pilkey. But academically, he’s not where he should be.

“He’s behind,” Cooley said. “He lost a year.”

In the fall of 2020, Ayden often missed out on daytime virtual school. His mother was looking for work, internet access was spotty and the “dynamics of the household,” Cooley said, weren’t conducive to keeping a 5-year-old in front of the computer.

Cooley shopped on Facebook Marketplace for a table and chair set so he could do his work and called his house every evening to make sure he logged into class.

“I knew I had to step in,” she said. “He’s in the fourth grade, and I’m still stepping in.”

When KIPP opened an optional hybrid program in March 2021, Ayden was there.

“He recognized me, and he was like ‘You came to my house!’ ” Fletcher said. “To this day, I’ll see him in the hallway, and he’ll just give me a hug.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter