Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Right before Congress powered down for the holidays, lawmakers passed the Autism CARES Act of 2024, appropriating nearly $2 billion to pay for a huge number of autism research, training and services programs. But even as disability advocates cheered, they sounded alarms regarding the impact Robert F. Kennedy Jr. could have if confirmed as head of the agency responsible for distributing the funds.

When the first iteration of the law passed in 2006, it was known as the Combating Autism Act. As that name suggests, its aim was to fund research into causes and potential cures, with the goal of eradicating the syndrome. In the nearly two decades since, disability advocates have won more seats on the committee that oversees how the money is spent, which involves nearly two dozen federal agencies. Given a say in what is prioritized, they have secured incremental increases in funding to develop services to improve autistic people’s lives, such as faster diagnosis, better special education strategies, communication technologies and effective mental health treatment.

Still, just 13% of federal funds are now spent on autistic people’s well-being, versus 63% on investigations into biology, genetics and potential environmental influences — some of it presumably in service of wiping out what advocates argue is a naturally occurring neurotype.

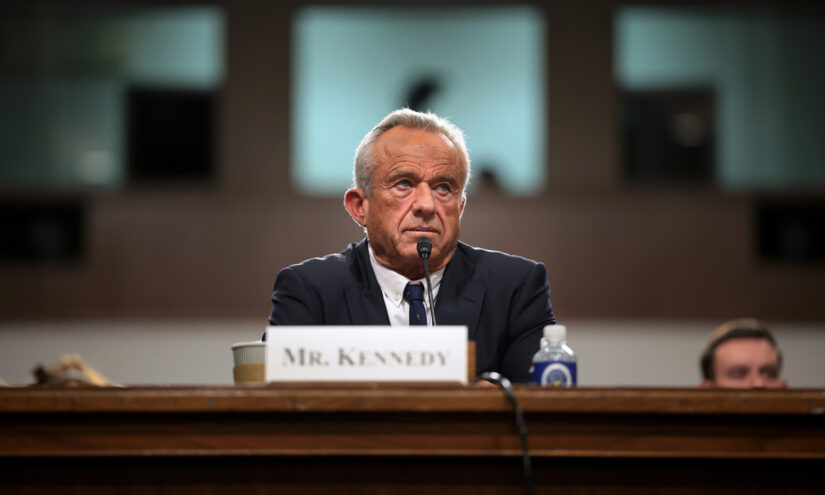

In recent, heated Senate confirmation hearings, the potential secretary of health and human services waffled when grilled about his repeated, false statements asserting that vaccines cause autism. Though hundreds of studies worldwide have ruled out a link, Kennedy called for a fresh — and presumably costly — review.

The idea that Kennedy could attempt to divert federal funding away from autistic people’s long-sought priorities to instead revisit established science has been deeply upsetting to many. Based on the offensive stereotypes Kennedy has used when talking about autistic people, many say they fear he will set back decades of progress if confirmed.

“[He thinks] it’s better to risk getting a deadly disease and your children dying than to be autistic,” says Zoe Gross, the director of advocacy at the Autistic Self Advocacy Network. “That’s obviously a very stigmatizing and fearmongering way to talk about autism.”

In 2015, she notes, Kennedy apologized for comparing autism, which he wrongly asserted destroys the brain, to a genocide caused by vaccines. “They get the shot, that night they have a fever of 103 [degrees], they go to sleep and three months later their brain is gone,” he told a Sacramento audience. “This is a Holocaust, what this is doing to our country.”

Advocates say Kennedy’s long history of talking about autism as something to be eradicated has alarming echoes of Nazi eugenicists’ campaign to “euthanize” autistic people, who were seen as a financial and genetic burden to society.

“This attitude toward autism is kind of a canary in the coal mine situation,” says Gross. “Kennedy’s beliefs about autism go hand in hand with some other really dangerous beliefs.”

Advocates also argue that Kennedy has financial conflicts of interest. He has earned a reported $2.5 million in fees for referring potential clients to a law firm pursuing a suit claiming the human papillomavirus vaccine, Gardasil, is unsafe.

Despite his family’s decades of staunch advocacy for improving the lives of people with disabilities, Kennedy believes autism was rare or nonexistent until 1989, often insisting that there were no profoundly autistic children when he was growing up and he does not know any autistic adults.

“I have never in my life seen a man my age with full-blown autism, not once,” Kennedy said in a 2023 radio interview. “Where are these men? One out of every 22 men who are walking around the mall with helmets on, who are non-toilet-trained, nonverbal, stimming, toe-walking, hand-flapping. I’ve never seen it.”

It’s generally accepted that much of the increase in positive diagnoses can be attributed to changes to criteria. Previously, children — and, in particular, girls — often went undiagnosed if their autistic traits were subtle. If the symptoms were more profound, the children were categorized as schizophrenic or having a developmental disorder instead. As a result, the number of kids with an autism diagnosis has risen from 1 in 150 in 2000 to 1 in 36 today.

Public schools are bound by the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act and portions of the Americans with Disabilities Act to provide a broad array of services to people with disabilities from birth to their 22nd birthday. Because of this, the CARES Act requires the Department of Health and Human Services to work in concert with the Education and Agriculture departments.

The CARES Act does not fund special education per se, but pays for research on effective instruction; technology to enable the 25% to 30% of autistic people who are nonverbal or minimally speaking to communicate; and to identify strategies to help autistic people who age out of special education find new services and ideally achieve independence, among other things.

In some places, the funds defray the cost of evaluating children as quickly as possible so they can get crucial early interventions, notes David Rivera, the president and founder of a California nonprofit, Mentoring Autistic Minds.

“The program has helped fund, in a single year, more than 100,000 people receiving diagnoses — or ruling them out,” says Rivera, who is autistic. “Diagnosis allows access to services.”

The latest version of the law requires the development of a strategy to address a desperate shortage of developmental-behavioral pediatricians, the providers most qualified to diagnose autism and assess children’s needs. Throughout the country, there are just 700, leaving families who are unable to have their children assessed through a school system to wait as long as two years or more for private evaluations.

Last year, Rivera lobbied for the law’s renewal, crediting it for “an explosion of research” undergirding effective strategies that helped him go from failing classes in elementary and middle school to gaining admission to the University of California, Berkeley, where he is a political science major.

Diverting federal funding from efforts like those that have made him successful is “the equivalent of throwing money into a fire,” Rivera says.

The 2024 version of the law is the fifth. Each time Congress has rewritten it, autistic people and advocacy organizations have lobbied to expand its scope to include funding for research and programs intended to improve autists’ lives.

As the public’s understanding of how many people are autistic — and how their autism manifests — changed, the law has been revised to require leaders of a host of federal agencies, such as departments of justice, labor, veterans affairs and housing and urban development, to participate on the on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee, which oversees how the money is spent.

Advocates have also fought to increase the number of committee seats reserved for members of the public who are autistic, parents and advocacy group leaders. The panel currently has a nonverbal member and one with an intellectual disability in addition to autism. New and returning members are appointed after each reauthorization.

Health and Human Services officials did not respond to a request from The 74 for comment, but as of press time, the committee’s website said the agency would solicit new public members in early 2025.

Right now, there are more caregivers and autistic members than are required by law, says Gross.

“Certainly they could go down to the bare minimum,” she says. “And I think it would be difficult to find self-advocates who have those same beliefs that vaccines cause autism, [but] I’m not going to say it’s impossible.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter