- Researchers have developed a new data set and evaluation tool to gauge how artificial intelligence models can analyze wildlife images beyond just identifying species.

- The tool, named INQUIRE, found that AI models didn’t perform well when asked to analyze more nuanced details from images captured by citizen scientists.

- The team that developed the tool, however, said that vision-language models have the potential to extract more data from wildlife photos, if trained extensively in the future.

How do you identify an animal in a photo? These days, a host of AI-driven apps are available that make this an easy task.

But what if you have more questions? Is the animal looking healthy? Are its surroundings polluted? Does it look stressed because of the heat? Getting these answers would be key to understanding how habitat degradation, pollution and global warming are adversely affecting biodiversity around the world.

Artificial intelligence might not be able to answer such intricate questions from an image just yet. However, the potential is there.

Researchers have developed a new data set and evaluation tool to gauge how AI models perform when asked for extra information from images captured and shared by citizen scientists. The INQUIRE tool was developed by teams at the University of Edinburgh, University College London, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, UMass Amherst and iNaturalist, a citizen science platform where people can share photos of plants and animals.

On applying the data set to various AI models and algorithms, researchers found that artificial intelligence performed well with simple prompts, but failed when more complicated ones were introduced. Nevertheless, the team said further work will enable AI models to help scientists gather more intricate and nuanced data from images taken by citizen scientists around the world.

Team member Oisin Aodha, associate professor in machine learning at the University of Edinburgh, told Mongabay that identifying species from photos is only the “tip of the iceberg.” He emphasized the need to capitalize on the millions of wildlife images already captured by citizen scientists to extract more information from them.

Image identification by AI models is itself a work in progress. Oftentimes, lack of training data prevents scientists from being able to build fully functional algorithms, especially for lesser-known species in remote regions. “We don’t want to give an impression that the core challenge is solved,” Aodha told Mongabay in a video interview. “There’s still a huge amount of work to be done in the categorization or identification of species.”

However, he said, the rapid development of vision-language models — generative AI models that can process text as well as images — prompted the team to start looking into how they could potentially be applied to extract additional information from photos.

The team was also motivated by an incident from a few years ago when researchers at the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles successfully crowdsourced photos showing the mating rituals of alligator lizards, a phenomenon that even researchers studying the species hadn’t been able to document firsthand. “It was something that people had documented on these citizen science platforms,” Aodha said. “This was a cool example of the fact that things that maybe one individual couldn’t see, a whole group of people might inevitably come up with.”

These developments got the team thinking: would it be possible for a researcher to type out intricate open-ended questions, have AI models parse through millions of images from around the world, and then come up with visual evidence for their hypothesis?

INQUIRE was built with the aim of finding an answer to that question.

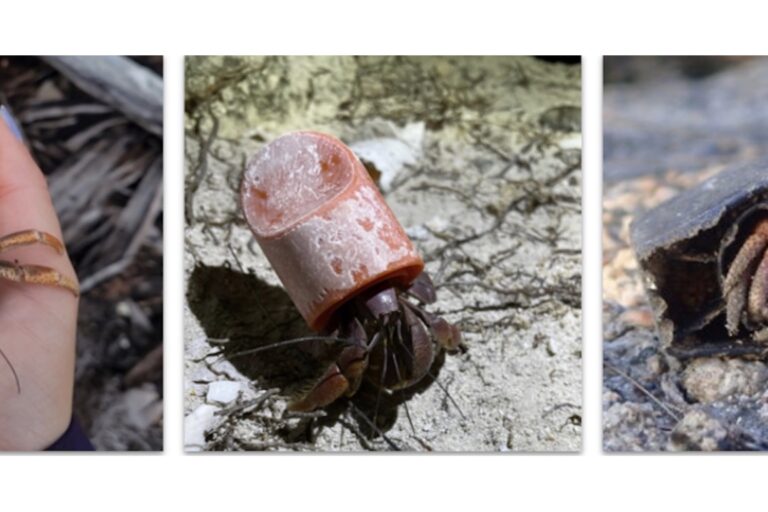

The data set was developed around 250 ecological prompts that the team framed based on discussions with ecologists, ornithologists and oceanographers. “A hermit crab using plastic trash as its shell,” “a sick cassava plant,” and “a California condor tagged with a green ‘26’” are among the prompts that the researchers applied to more than 5 million images on iNaturalist. This means that for each of those prompts, they went through each image and labeled it to say if it was relevant to the prompt or not. In the end, they found 33,000 images that matched the descriptions in the prompts. This data set was then used to train other AI models and to test how they performed when a new image was introduced into the mix.

Current AI models, the team found, have a long way to go when it comes to detecting the finer and subtler details in images. For example, Aodha said, models couldn’t tell between a California condor with a tag that shows “26” and another type of condor with a tag showing the same number. “The challenge is how do we get these huge models which have very general knowledge, and get them to learn specialized information,” he said.

The other big hurdle is to think through how to make these models more efficient. Each time someone types in a prompt, the model will have to go through millions of images. “That’s something, if done inefficiently, could be prohibitively expensive and would use so much resources and energy that it would be irresponsible to use it,” Aodha said.

However, if they manage to move past those hurdles, Aodha said he sees vision-language models having immense applications in ecological research and biodiversity protection.

For instance, if a scientist is curious about human-induced pressures threatening a particular species, they could formulate questions and use those models to trawl through images from around the world. Aodha said it would help them find visual evidence for their queries and might potentially serve as a starting point for their research.

“Normally, it would take so long that it might prohibit them from doing it,” Aodha said. “This might be a way to supercharge it.”

Abhishyant Kidangoor is a staff writer at Mongabay. Find him on 𝕏 @AbhishyantPK.

Banner image: INQUIRE, a dataset and evaluation tool, gauges how AI models perform when asked to extract extra information from wildlife photos captured by citizen scientists. The three images (above), showing hermit frogs caught in plastic trash, were clicked by citizen scientists and were used to train the dataset. Images by mferrla (left), anacarohdez (middle) and lexthelearner (right)/iNaturalist.