Deforestation affects local climate by altering the water balance, wind patterns, and heat and radiation fluxes between the Earth’s surface and the atmosphere. Owing to the interplay of these effects, the overall influence of deforestation on rainfall has been notoriously difficult to quantify, especially for data-scarce regions, such as the Amazon rainforest. Moreover, studies have tended to focus on annual average effects, neglecting seasonal variations. Writing in Nature, Qin et al.1 report an analysis of satellite data and climate simulations that uncovers seasonal rainfall changes in the Amazon after deforestation. Their results reveal that deforestation increases rainfall during the wet season but lowers it during the dry season, when vegetation depends most on local water cycling.

Read the paper: Impact of Amazonian deforestation on precipitation reverses between seasons

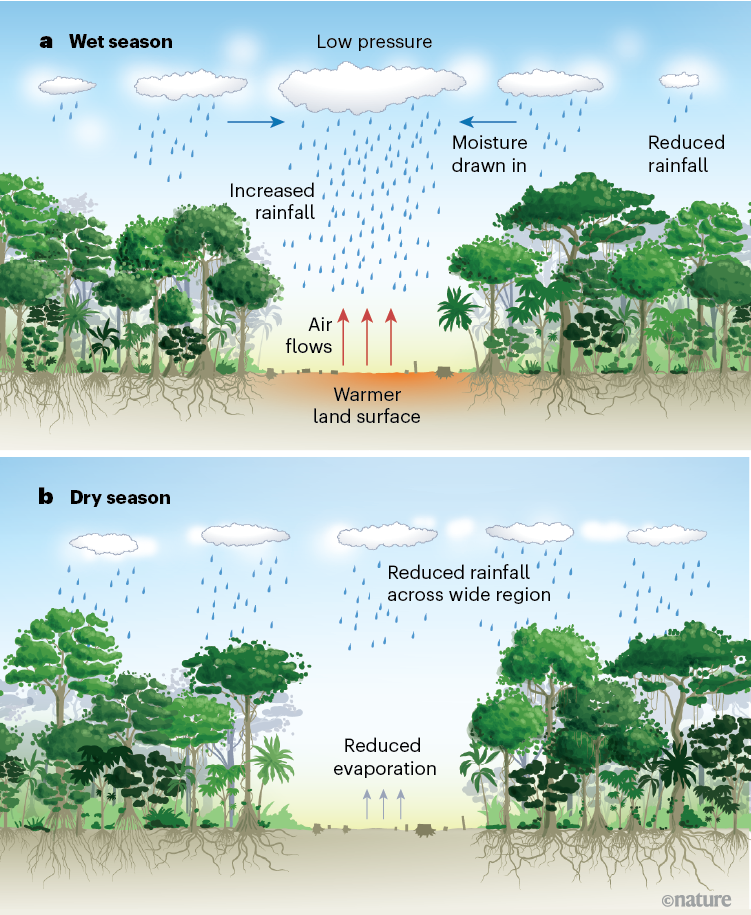

Tree clearance in the tropics has two main effects that drive rainfall responses. First, the amount of water that evaporates from vegetation is reduced, decreasing the amount of moisture that enters the atmosphere and thus lowering rainfall potential. Second, deforestation can cause the land surface to become relatively warm, triggering upward air flows and the formation of areas of low atmospheric pressure. Such ‘heat lows’ draw in moisture from upwind areas and thereby increase cloud cover and rainfall over deforested patches — but at the expense of rainfall in the upwind areas. Depending on the specific location and which of the two effects dominates, rainfall can either increase or decrease in deforested areas.

Changes in moisture input and redistribution in the atmosphere matter for rainfall patterns, especially in the Amazon, where about one-third of all rainwater originates from the Amazon basin itself2. The existing balance between the origin and fate of water is essential for the health of the rainforest in this region, yet the interplaying factors involved are strongly perturbed by climate change and deforestation. The situation is further complicated by the fact that deforestation also contributes to global climate change, as a result of carbon trapped in forest ecosystems being released to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide3.

Observed reductions in rainfall due to tropical deforestation

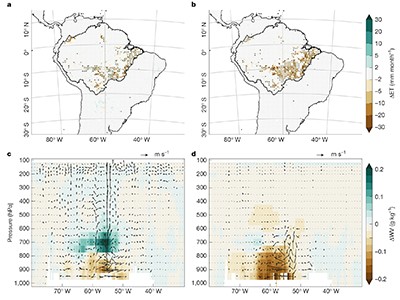

Qin et al. take on the challenge of quantifying how Amazon rainfall has responded to deforestation, using a combination of satellite data sets and simulation experiments. The authors use an innovative approach: they track moisture as it moves through the climate system using a regional climate model centred over South America. By comparing transient climate simulations with forest maps of the years 2000 and 2020, they determine the influence of deforestation on the amount of moisture passing into, through and out of the atmosphere.

The authors find that, during the wet season (December to February), deforestation triggers the transport of atmospheric moisture towards cleared forest patches, increasing rainfall locally while reducing rainfall upwind (Fig. 1a). This means that heat lows and associated wind-circulation responses are the dominant effects during the wet season. By contrast, the dominant effect during the dry season (June to August) is decreased evaporation from vegetation, reducing atmospheric water availability and rainfall across the wider region (Fig. 1b). The simulations and satellite data consistently show this seasonal contrast, reinforcing the reliability of the findings.

Figure 1 | How deforestation affects local rainfall seasonally in Amazonia. Qin et al.1 tracked atmospheric moisture in a regional climate model of the Amazon region to determine the effects of deforestation on rainfall. a, The authors find that, during the wet season, deforestation causes rainfall over deforested areas to increase, but lowers rainfall over upwind areas. This is because deforestation causes the land surface to become relatively warm, triggering upward air flows and the formation of areas of low atmospheric pressure. This draws in moisture from upwind regions, increasing rainfall over the cleared forest — at the expense of precipitation in the upwind areas. b, During the dry season, deforestation causes a reduction in rainfall across a wide region. This is because the amount of moisture that enters the atmosphere as a result of water evaporating from vegetation is reduced by deforestation, lowering rainfall potential.

Further research could build on Qin and colleagues’ pioneering study in several ways. For example, the statistical approaches currently used to tease out the effects of deforestation from climate data sets tend to overemphasize local responses to changes in land cover4, so theoretical work could aim to overcome this problem. Moreover, the simple separation of effects into ‘local’ and ‘non-local’ responses in the current study could be improved by further splitting non-local responses into mesoscale effects (such as forest breezes) that redistribute moisture on scales of 10–1,000 kilometres and large-scale circulation responses, which alter moisture transport from over the oceans to the Amazon basin. Global climate simulations that consider idealized deforestation patterns, such as those in which trees are removed from alternating cells of a grid on a map, show promise for resolving the effects of deforestation at these two scales5. Finally, moisture-tracking analyses could be used to unveil the downwind drought risks of upwind climate change and deforestation6.

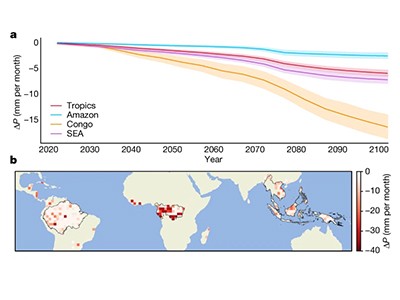

‘We are killing this ecosystem’: the scientists tracking the Amazon’s fading health

Deforestation was initially a problem at mid-latitude regions, but it has intensified in tropical regions such as the Amazon basin, the Congo Basin in Africa and southeast Asia since 20007. These tropical regions will continue to be global hotspots of deforestation unless decisive action is taken to halt it8. Heat lows might drive future local rainfall increases over deforestation hotspots in the Congo Basin9, whereas further tropical deforestation in the Amazon is expected to cause drying across that region10. To make matters worse, the deforestation-induced drying in the Amazon will be exacerbated by the further drying that is expected to occur as a result of continued greenhouse-gas emissions11.

Reduced rainfall under compounding deforestation and climate change could cause vegetation to degrade and to evaporate less water — exacerbating the decrease in rainfall still further and potentially triggering a feedback mechanism that could lead to widespread dieback of the Amazon forest. Specialists estimate that the Amazon could tip into a savannah-like state if warming reaches 2 °C above preindustrial levels12. The combined effects of warming and deforestation could put 10–47% of Amazon forests at risk of unexpected ecosystem transitions as soon as 205013.

The frontier of current research, therefore, lies in advancing analytical frameworks, such as the one presented by Qin et al., by coupling them with dynamic modelling of vegetation. Only when the interacting effects of climate change, deforestation and vegetation health are linked can the risk of tipping be truly assessed. Considering seasonality — as Qin et al. have done — as well as drought and heat extremes will be essential steps in this process.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.