Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Americans want civics — even the role of politically charged topics like immigration and gun control — taught in school. Since 2021, there’s been increasing bipartisan support for students to learn about how the government works, a new survey finds.

The increases, while modest, are being driven by Republicans. Greater percentages of GOP voters say they want students to study social safety net programs like welfare and Medicaid. While there’s still a partisan divide on such topics, 51% of Republicans support students learning about income inequality, compared to 46% in 2021. Support among Democrats held steady at 87%.

“People are supportive of schools teaching about controversial topics from multiple perspectives,” said Morgan Polikoff, a University of Southern California education professor and co-author of the study, drawn from a sample of 4,200 adults, including almost half with school-age children. “They don’t want teachers to be putting their thumb on the scale in terms of one perspective being better than the other.”

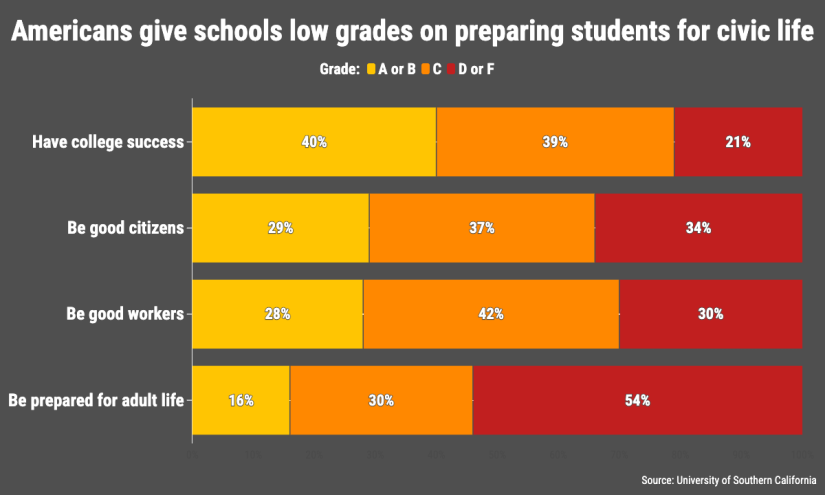

The shift comes even as Americans of all political stripes give schools low marks on preparing students to be good citizens, with just 29% offering them an A or B grade.

But the increasing support among Republicans for teaching issues frequently labelled divisive surprised researchers, suggesting that many conservatives don’t necessarily want to limit what children learn in school — a frequent criticism lodged by critics on the left. Most red states have either banned or considered legislation outlawing the teaching of what Republicans consider divisive concepts. Critics say the mandates have silenced teachers interested in presenting a full account of American history, including its darker chapters.

The survey also shows Republicans want more attention paid to current events, such as the benefits and challenges of Medicare and Social Security (69%, up from 62% in 2021). The share of Republicans who believe schools should teach about racism also increased, from 54% to 58%.

“Contrary to the conventional wisdom, there are still plenty of educational issues that garner bipartisan support in this polarized era,” said David Houston, an assistant education professor at George Mason University. “Finding these points of convergence is an important and necessary step toward building broad and durable support for public education in both red and blue communities and from one presidential administration to the next.”

Jonathan Butcher, a senior research fellow at the right-wing Heritage Foundation, said he prefers a “more conservative approach” to civics that would focus on the Constitution and structures like the electoral college. But he said it’s also “certainly justifiable” for schools to teach students how to interpret the news of the day — like why Democrats held up signs reading “Save Medicaid” during President Donald Trump’s speech to Congress Tuesday night.

“As we teach students about civics, they should understand how Medicaid came to be, what the relationship is between taxpayers and Medicaid,” he said. “Students should have enough background knowledge and an understanding of how policies have been formed that they can understand what was happening.”

Teaching ‘with nuance’

Florida is among the red states that prohibit teachers from discussing topics like institutional prejudice or gender equity. The state’s law bans educators from teaching that someone might be “inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive.”

The law is “commonly known for restricting instruction,” said Stephen Masyada, director of the Florida Joint Center for Citizenship at the University of Central Florida. But he thinks that characterization ignores that the legislation also requires students to learn about “the ramifications of prejudice, racism and stereotyping on individual freedoms.”

The state mandates lessons, for example, on the Ocoee Election Day Massacre in 1920, when a white mob killed dozens of Black citizens and ran hundreds more out of town in a violent attempt to keep them from voting.

Many conservatives want schools to address those topics “with nuance,” Masyada said, and to connect “the promises of the founding era” to overcoming oppression and bias.

‘Very nationalistic’

Some current examples of civics education remain too liberal for many Republicans. “We the People: Civics that Empower All Students,” a training program for teachers in grades four through eight, was among the programs eliminated in the U.S. Department of Education’s sweeping cancellations of teacher preparation grants last month. The program equips teachers to focus on topics like the Bill of Rights, but also encourages civic engagement. Some conservatives argue that such projects emphasize liberal causes like abortion rights or climate activism. The department said grantees “were using taxpayer funds to train teachers and education agencies on divisive ideologies.”

The USC survey shows that the percentages of Republicans saying schools should teach the contributions of women and minorities throughout history — topics that could be construed as promoting diversity, equity and inclusion — were relatively flat or saw a small decline. Among Democrats, however, there were increases.

“Everybody likes civic education, but they like it for different reasons,” said Marcie Taylor-Thoma, director of the Maryland Council for Civic and History and a former social studies coordinator for the state. Democrats, she said, think students should learn about their civil rights and “critically analyze what’s going on in our country.” But Republicans’ view of civics is “very nationalistic” she said.

There’s little disagreement, however, over teaching students about the U.S. Constitution. Ninety-three percent of Democrats and 95% of Republicans said it’s important for any civics curriculum to cover the rights and principles outlined in the founding document. It’s a cause that many chapters of Moms for Liberty, a conservative advocacy group, have taken up in recent years, and a Trump executive order calls for schools to recognize Constitution Day annually on Sept. 17.

There was scant support in the survey for students participating in protests during school hours — only 24% liked the idea — but the largest partisan split was over reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. Forty-four percent of Democrats support that tradition, compared with 84% of Republicans. Debates over requiring students to recite the pledge have erupted in recent years in Maryland and Vermont.

Given the negative attitudes of many respondents toward the role schools play in preparing students for civic life, researchers thought support would be higher for a common political proving ground: student government. But less than three-fourths of respondents favor student participation in school elections, like voting for student council leaders.

That finding was unexpected, said Anna Saavedra, lead author and a research scientist at USC’s Center for Applied Research in Education.

“Having a class president is a pretty standard part of most schools,” she said. “Seeing such low support was a little surprising. It’s a way for kids to practice voting, running a platform and participating in a democratic process.”

Polikoff said it’s not surprising that there are differences of opinion over activities like requiring community service as part of classwork (73% of Republicans compared with 80% of Democrats) or honoring veterans and military service (92% of Republicans and 78% of Democrats). Local context, he said, will continue to influence how deep teachers can take classroom discussions on potentially controversial topics.

“I don’t think that we would expect that the civics curriculum is going to look exactly the same in rural Republican Wisconsin as it’s going to look in Oakland Unified [in California],” he said. “In both places, there is room for diverse perspectives. The reality is, every classroom is purple to at least some extent.”

‘A challenge to teach’

Some educators, however, still tiptoe around topics in the news.

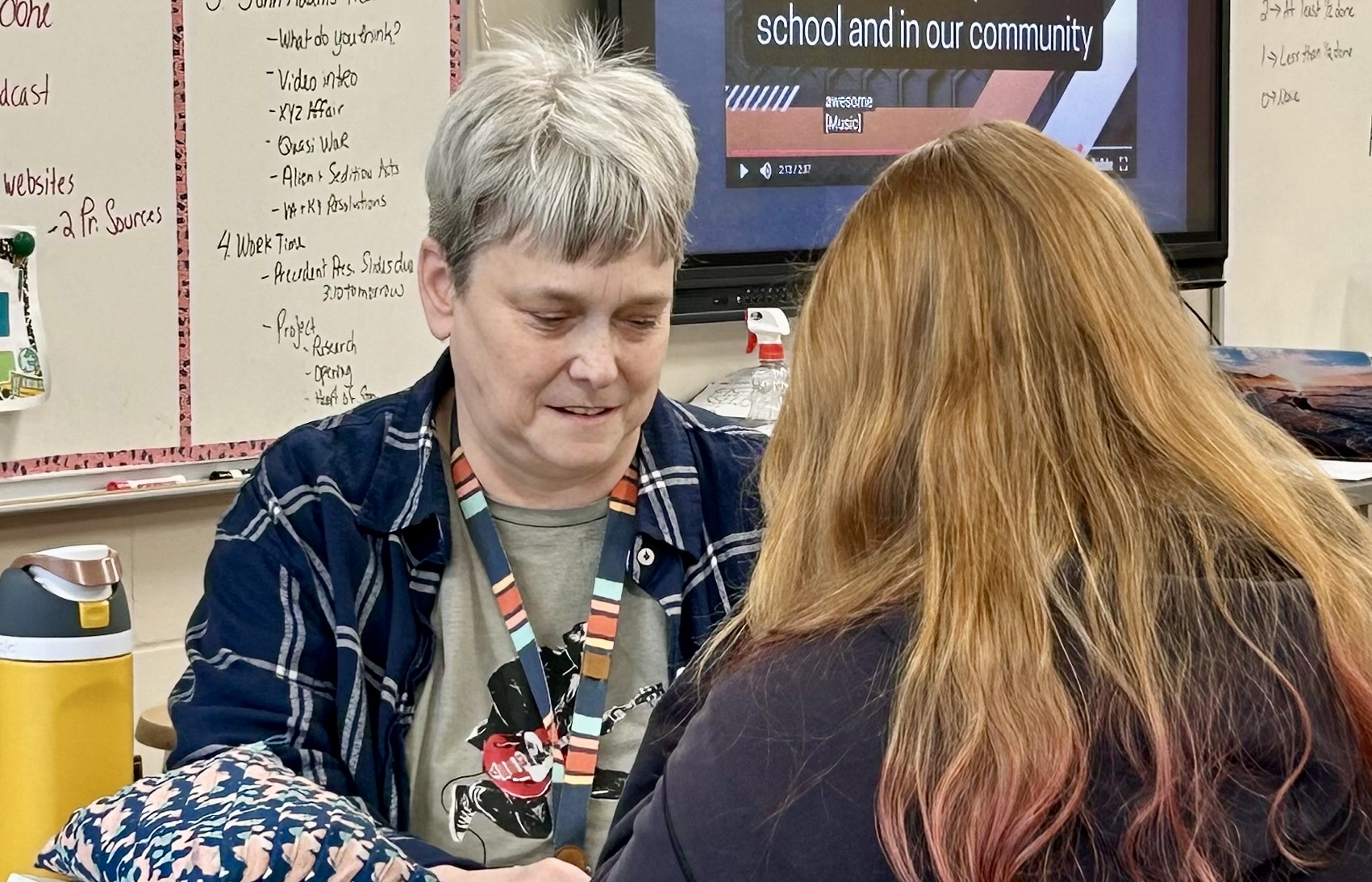

“It’s been a challenge to teach lately,” said Jenny Morgan, a veteran eighth grade U.S. History teacher in the West Salem, Wisconsin, district, which she described as “very, very Republican.”

She’s tried to avoid discussing President Donald Trump’s and Elon Musk’s makeover of the executive branch, but she did recently teach a lesson on tariffs, which Trump is charging Canada, China and Mexico.

The discussion prompted a recent debate between two students on opposite sides of the political spectrum.

“The Democratic student was trying to explain why tariffs aren’t good and talked about how prices are going to go up. The other kid was saying ‘Oh no, they won’t go up,’ ” Morgan said. “It was just an interesting conversation between the two eighth grade boys. You could tell they were getting current events at home.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter