The two foremost satellite fairs of Mexico City’s Art Week—Salón Acme and Material, now in their 12th and 11th editions, respectively—drew large crowds to their openings a few blocks apart the day after Zona Maco held its VIP preview. At Expo Reforma, the venue for Material and the upstart design fair Unique Design X, visitors filled the aisles and common areas on Thursday (6 February). The 72 exhibitors at Material, hailing from 20 countries, include a strong contingent of galleries from Mexico, Peru, Argentina and Colombia.

“This year is the highest percentage to date of galleries participating from Latin America,” says Brett W. Schultz, the fair’s co-founder. “It’s important that Material be a viable platform for galleries from Buenos Aires, Santiago, Lima, etc. And a lot of the participating galleries from the UK and US are showing artists who are from Latin America, have Latin American heritage or are based here.”

New York-based Swivel Gallery, for instance, has a solo stand of works by the Cuban American artist Amy Bravo, whose mixed-media sculptures are intensely personal yet have a strong material pull with their combinations of wax, bones, textiles, found objects and more. Many works incorporate casts of the artist’s own face, as well as mannequin limbs and creature imagery like spiders and bulls. The stand’s centrepiece, a human figure on hands and knees, embedded with imagery and topped with a bull skull, sold for $14,000 before the end of the opening day, while smaller wall-based works are available for $7,500.

Amy Bravo’s The Strongest Man, The Living Weapon (2024, left) and The Seamstress (2024, right) on the Swivel Gallery stand at Material Courtesy the artist and Swivel Gallery, New York

“Her work is about her family and her heritage,” says Aida Valdez, a Mexico City-based art adviser working on the Swivel stand. “She uses a lot of symbolism in her work—the bull represents her father, and she is the spider. The work is also a bit of a rebellion against macho culture—she’s making very muscular sculptures.”

Muscles, bones, tendons and limbs of various sorts are surprisingly frequent features across the satellite fairs. In the next aisle over from the Swivel Gallery booth, the Mexico City-based gallery Pequod Co’s stand includes within its group presentation a sculpture by the Tijuana-born artist Andrew Roberts that consists of a hyperrealistic severed zombie leg covered in cuts and tattoos, presented in a high-end, padded carrying case. The work, Remake, reshoot, reprise: a ghoul had to pay its debt to the sun (2024), is priced at $8,000 and incorporates medical-grade silicone and builds on the artist’s work with cinematic and videogame software.

“His work is dealing with the normalisation of violence and constant migration across the Mexico-US border where he’s from in Tijuana,” says the gallery’s co-founder and co-director Mau Galguera. “Andrew is always exploring the idea of otherness, and how when the other is not understood it becomes feared.”

Talia Pérez Gilbert’s Abominable Enter Infernal (2025) on the Sala de Espera stand at Material Benjamin Sutton

Another severed limb emblematic of fear and otherness—also of Tijuanan origin—is on view in Material’s Proyectos sector, which provides small stands free of charge to experimental and artist-run spaces, as well as the mentorship of more established dealers. The art space Sala de Espera has partially recreated its home base in Tijuana, which is inside an abandoned illegal hospital, complete with faux wood panelling and a trio of garish waiting room seats. On the middle seat sits Talia Pérez Gilbert’s sculpture of a furry, disembodied hand, Abominable Enter Infernal (2025), which is priced at $1,000. Made of wax, acrylic, hair, fabric and a cufflink, it is based on an urban legend about a malevolent hairy hand, la mano peluda, and a popular radio show of the same name where people call in to share horror stories.

“The installation is called Faith, Hope and Fraud, and it is based on the headline of a Los Angeles Times article from 1991 about the doctor who ran the clandestine hospital where we are based, Jimmy Keller,” explains Luis Alonso Sánchez, who co-directs Sala de Espera with Gilbert. The stand also includes an appropriately scary sculpture of a screaming, Munchian figure by Luis Alonso Sánchez, a reinterpretation of a pornographic collage found at an underground bar inside the abandoned hospital, by Gabriel Boils Terán, and a selection of works on paper by all three featured artists, priced between $100 and $200.

Sánchez adds: “We always talk about how Tijuana has no history, so we’re trying to commemorate its past in this current moment of chaos and anxiety at the border.”

A sculpture by Berenice Olmedo on the Lodos stand at Material Benjamin Sutton

The stand of the Mexico City-based gallery Lodos includes two sculptures by Berenice Olmedo, who salvages and reconfigures prosthetic limbs to create freestanding figures that are at once otherworldly and distinctly human. The shorter work, featuring a lumpy and transparent mauve torso balancing atop prosthetic legs, is priced at $32,000, while a taller piece featuring long, orange legs and a blue torso, is priced at $64,000.

“Berenice primarily works with materials from the medical world,” says Javier Amescua, a sales associate at the gallery. “Her early work in this vein started because while she was salvaging materials from landfills she kept finding all these discarded prostheses for infants.”

For Schultz, practices like Bravo’s, Roberts’s, Gilbert’s and Olmedo’s—and the types of spaces championing them—are emblematic of Material’s mission. “There is a lot of really strong sculpture this year, which is a change from the pandemic years, when dealers were more reliant on paintings because they’re seen as a safer bet,” he says. “We’ve tried to keep the fair relatively affordable as a way to foster experimentation, and it seems to be working.”

Visitors at Salón Acme watch Julieta Gil’s video Millefleur (Milflores) (2025) Benjamin Sutton

Salón Acme, also taking place in the Juárez neighbourhood at Proyectos Públicos, likewise offers relatively affordable spaces to exhibitors across its three main sectors: Estado, where artists and galleries from a specific Mexican state are showcased each year (this year, Veracruz); Proyectos, for solo presentations, curated by the fair’s director Ana Castella; and Convocatoria, which is based on a committee’s selection from an open call that this year received around 1,800 submissions.

“We’re always looking at how our galleries might cooperate and collaborate, finding affinities in their programmes so they can share resources,” Castella says. “I like to make sure the three main sectors gel, but we also want to allow room for surprises—and there are always surprises. The newer galleries always put so much effort and professionalism into their presentations.”

Alan Sierra’s per angostam viam (2025) on view in Nixxxon’s space at Salón Acme Benjamin Sutton

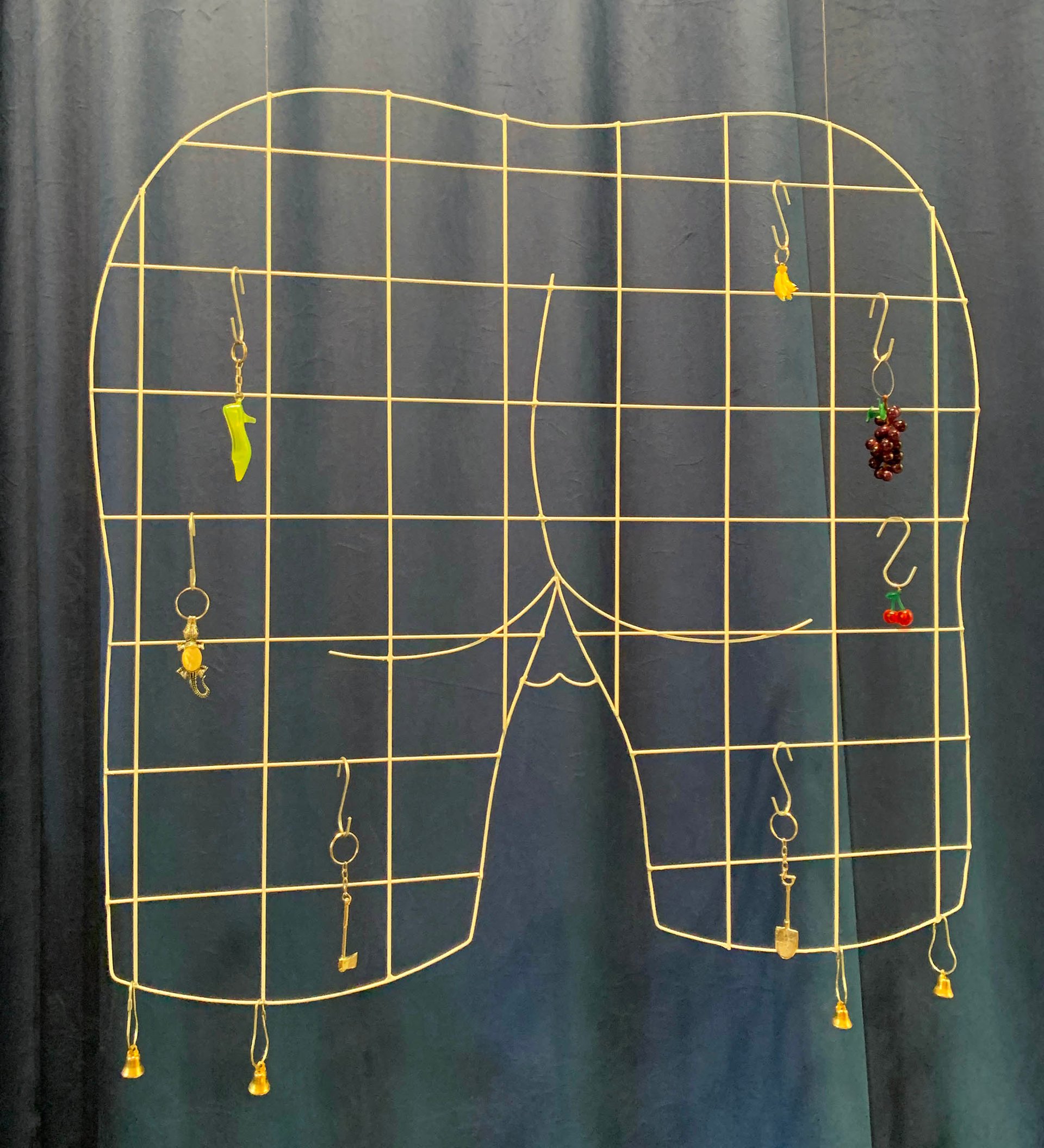

Among the standout presentations is a room in the Proyectos sector where the Mexico City-based gallery Nixxxon is showing metal grid sculptures in the shapes of various body parts—including a hand, a butt and a torso—by the local artist Alan Sierra. Priced between $1,000 and $3,500, the sculptures build upon Sierra’s long-running drawing practice; the gallery is also offering works on paper for $700 to $800.

“I walk the streets in this neighbourhood every day on my way to my studio, and see all these vendors displaying their wares on these metal grids,” Sierra says. “It occurred to me that these grids are a kind of exhibition device.” The butt sculpture for instance, per angostam viam (through narrow paths, 2025), has various hooks, kitschy keychains and trinkets hanging from it, including a tiny shovel, a bunch of bananas and a crocodile. The artist adds: “I wanted to make sculptures you could play with and modify.”

A work by Florencia Rothschild in the Veracruz sector of Salón Acme Benjamin Sutton

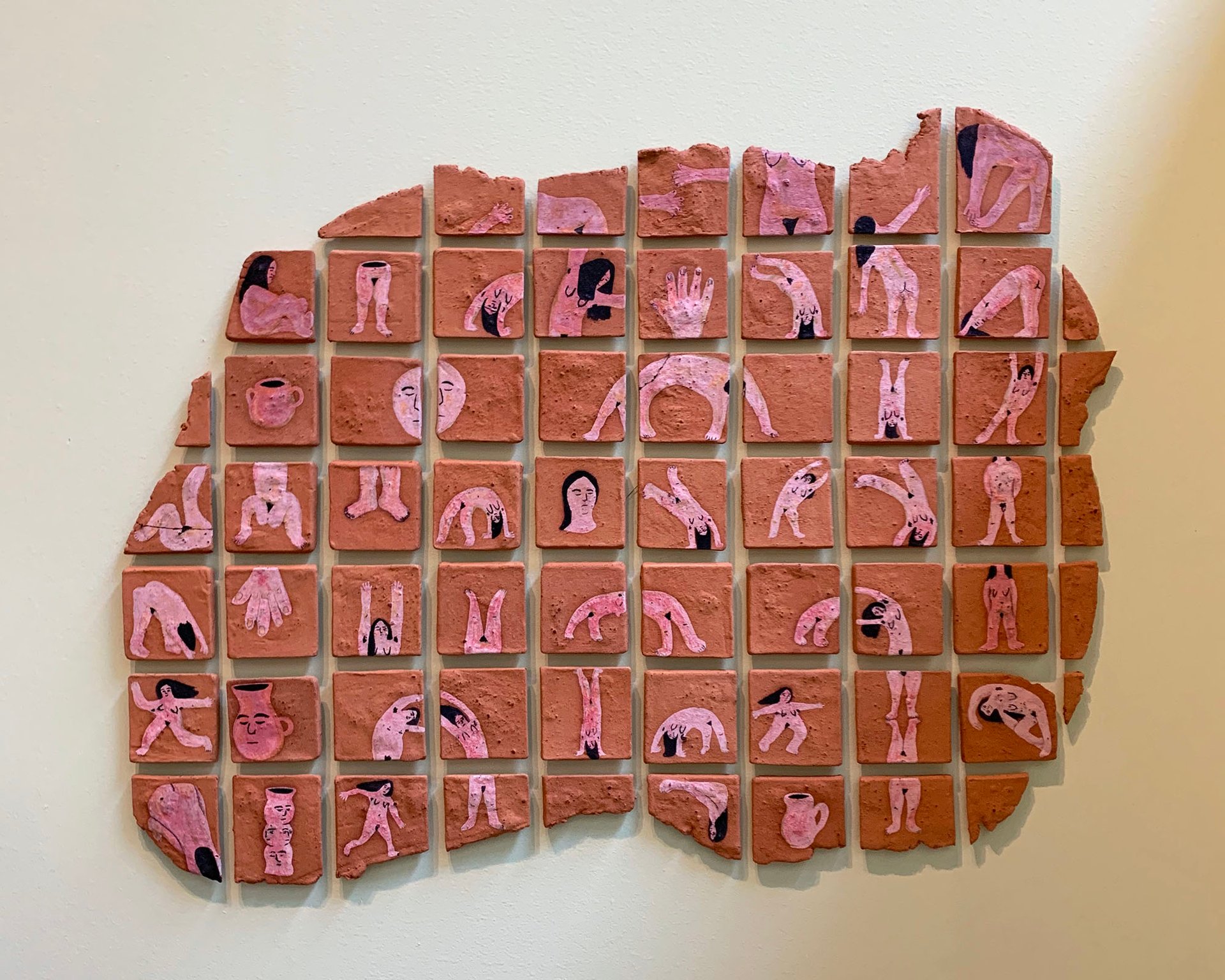

Another playful and bawdy group of works, in the Estado: Veracruz sector curated by Rafael Toriz, is by the Buenos Aires-born, Coatepec-based artist Florencia Rothschild. Small nude figures are painted across more than a half-dozen of her ceramic sculptures, ranging from tiles and vases to more abstract forms. By the middle of the fair’s second day (7 February), all but one—a wall-mounted work priced at $900—had sold.

Castella says the majority of buyers in Salón Acme’s opening days have been from the US and Mexico, and that groups and representatives from North American museums—including SFMoMA, the Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles and the National Gallery of Canada—visited during the preview. She adds: “It’s a great moment for the city, the fairs and galleries are all doing strong work, and the sales have been fantastic.”

Both Castella and Schultz say that fears of a possible Mexico-US trade war sparked on by Donald Trump’s threatened tariffs have not had a measurable impact on activities during Mexico City’s Art Week. Schultz says: “For a lot of the Americans who are here, it’s an opportunity to get away from all that.”

- Material, until 9 February, Expo Reforma, Juárez, Mexico City

- Salón Acme, until 9 February, Proyectos Públicos, Juárez, Mexico City