Terminology

Throughout this report, religious switching refers to a change between the religious group in which a person says they were raised (during their childhood) and their religious identity now (in adulthood). The rates of religious switching are based on responses to two survey questions we asked of adults ages 18 and older:

- “What is your current religion, if any?”

- “Thinking about when you were a child, in what religion were you raised, if any?”

The responses to these two questions allow us to calculate what percentage of the public has left a religious group (or “switched out”) and what percentage has entered (or “switched in”). This kind of switching can take place without any formal rite or ceremony.

We have analyzed switching into and out of five widely recognized, worldwide religions to allow for consistent comparisons around the globe. Specifically, this report analyzes change between the following groups: Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, other religions, religiously unaffiliated adults, and those who did not answer the question.

For example, someone who was raised Buddhist but now identifies as Christian would be considered as having switched religions – as would someone who was raised Christian but is now unaffiliated.

However, switching within a religious tradition, such as between Catholicism and Protestantism, is not captured in this report. (Refer to Pew Research Center’s 2023-24 Religious Landscape Study for an analysis of switching in the United States that does count some switching within Christianity. Read “4 facts about religious switching within Judaism in Israel” for an analysis of switching within Judaism.)

Religiously unaffiliated refers to people who answer a question about their current religion (or their upbringing) by saying they are (or were raised as) atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.” This category is sometimes called “no religion” or “nones.”

Other religions is an umbrella category. It contains a wide variety of religions that are not in the other categories and that have survey sample sizes too small to analyze separately in most countries. This includes Sikhism, Jainism, the Baha’i faith, African traditional religions, Native American religious traditions, and others.

Disaffiliation rates refer to the percentage of adults who say they were raised in a religion but are now religiously unaffiliated (or have no religion).

Net gains/losses are the differences between the percentage of survey respondents who say they were raised in a particular religious category (as children) and the percentage who identify with that same category at the time of the survey (as adults). The “net” gain or loss takes into account both sides of the equation – those who have left and those who have entered the group.

Retention rates show, among all the people who say they were raised in a particular religious group, the percentage who still describe themselves as belonging to that group today.

Accession rates (also called entrance rates) show, among all the people who describe themselves as belonging to a particular religious group today, the percentage who were raised in some other group.

This section takes a closer look at religious switching into and out of Christianity by reviewing where Christianity has had the largest net losses, what percentage of adults who were raised Christian are still Christian (i.e., retention rates), which religious groups people who left Christianity have switched into, and where Christianity has the largest shares of new entrants (i.e., the highest accession rates).

Of the 36 countries surveyed, 27 have sufficient sample sizes of Christians to allow analysis of religious switching into and out of Christianity.

Net losses for Christianity

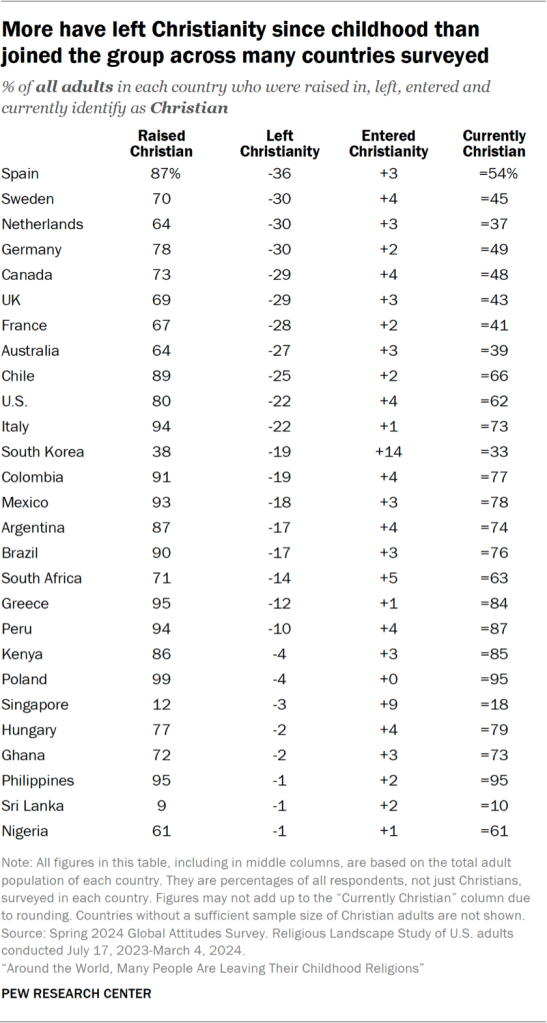

- More people have left Christianity than have joined it in many of the 27 countries analyzed.

- Spain has the largest net losses for Christians from religious switching (in proportion to the size of its population) of any country surveyed.

Remaining Christian

- In nearly all countries, majorities of Christians have retained their religion. This is especially true in the Philippines, Hungary and Nigeria, where nearly all people who say they were raised Christian are still Christians as adults.

Leaving Christianity

- Most who have left Christianity no longer identify with any religion, saying they are now atheist, agnostic or have no religion in particular.

- In some Asian countries, small shares of those raised Christian now identify as Buddhists.

Entering Christianity

- Singapore and South Korea have relatively high rates of “accession,” or entrance, into Christianity, with about four-in-ten or more Christian adults in these countries saying they were raised in another religion or with no religion. However, Christians remain a minority in both countries: 18% of Singaporeans and 33% of South Koreans currently identify as Christian.

- Among those who have switched into Christianity, many say they were raised Buddhist or without a religion.

Where has Christianity experienced the largest net gains and losses from religious switching?

In many countries surveyed, more people were raised as Christians and have left Christianity than have become Christians after being raised in some other tradition or without a religious affiliation.

In other words, Christianity has experienced an overall or “net” loss in adherents due to religious switching in many places.

For example, Spain has the largest net losses for Christians in percentage terms (as a proportion of the country’s total adult population) of the 27 countries analyzed.

The vast majority of all Spanish adults surveyed (87%) say they were raised Christian. But far fewer (54%) describe themselves as Christians today – a net loss for Christianity of one-third of all Spanish adults (that is, 33% of the total adult population, not just of current Christians).

This loss has occurred because 36% of Spanish adults have left Christianity (i.e., they were raised Christian but no longer identify as such) while just 3% of Spanish adults have entered Christianity (i.e., they identify as Christians today but say they were not raised that way).

Even in South Korea – the country with the largest share of adults raised outside of Christianity who now identify as Christian – more people have left Christianity (19% of all South Korean adults) than have entered Christianity (14%), a net loss for Christians that is equivalent to 5% of South Korea’s total adult population.

This trend is especially strong in many high-income countries. The survey finds that Christianity has sustained net losses due to switching of 20 percentage points or more of the total adult populations in Spain, Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, Chile, the United States and Italy.

On the other hand, the pattern is not universal. In Singapore, which is also a high-income country, a larger share of adults have joined Christianity since childhood than have left Christianity. While 12% of Singaporean adults say they were raised Christian, 18% currently identify as Christians. This means Christianity has seen a net gain of 6% of all Singaporean adults.

What percentage of people raised Christian are still Christian?

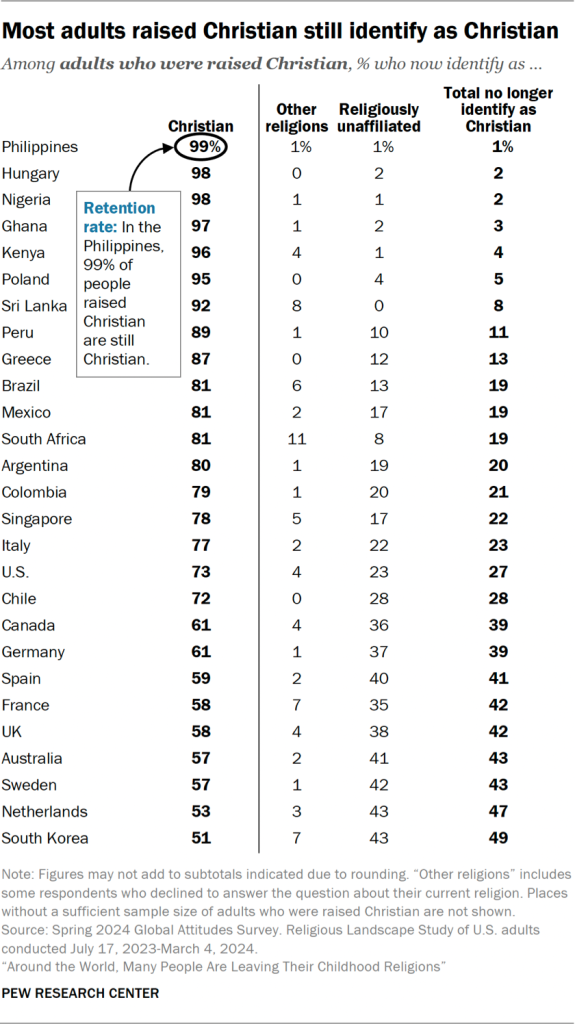

In most countries, majorities of adults who were raised Christian still identify as Christian today. We call this religious “retention.”

Christian retention rates vary widely, however. The highest are in the Philippines, Hungary and Nigeria, where nearly all adults who were raised Christian are still Christian today.

Across the countries analyzed, the lowest retention rate among Christians is in South Korea. About half of Koreans raised Christian still identify as Christian (51%), while the other half (49%) are no longer Christian.

Which religious groups have former Christians switched to?

Analyzing retention rates also sheds light on the religious groups that former Christians have joined. Across most countries surveyed, the majority of adults who have left Christianity say they no longer identify with any religion.

For example, in Australia, 41% of adults raised Christian now identify with no religion, compared with just 2% of Australian adults who were raised Christian and have left Christianity for some other religion.

In some Asian countries, small shares of those raised Christian now identify as Buddhist. This includes 7% of those raised Christian in Sri Lanka and 6% in South Korea.

Where does Christianity have the largest shares of new entrants?

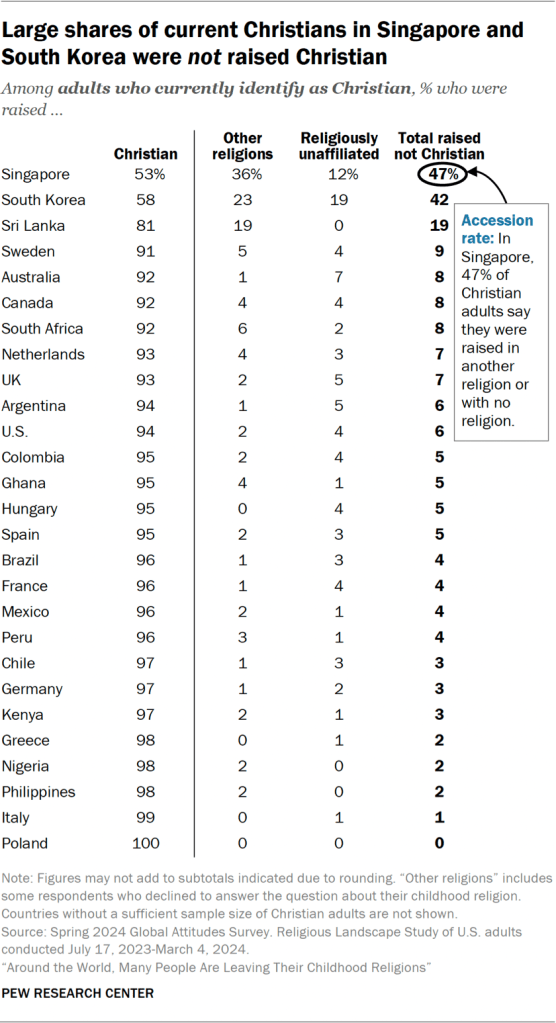

In the countries with sufficient sample sizes of Christians to analyze, most people who currently identify as Christian were raised Christian. For example, virtually all Polish Christians surveyed say they were raised as Christians.

But in a few places, large shares of those who describe themselves as Christians say they were not raised this way. We refer to this as “accession,” or entrance, into Christianity.

In particular, three countries surveyed have accession rates higher than 10%: Singapore, South Korea and Sri Lanka. Just under half of Singaporean Christians (47%) say they were raised outside Christianity.

In Singapore and South Korea, sizable shares of Christians were raised Buddhist (17% each) or with no religion (12% and 19%, respectively). In Sri Lanka, the 19% accession rate for Christians is made up entirely of former Hindus (10%) and former Buddhists (9%).