(© Sylvie Pabion Martín – stock.adobe.com)

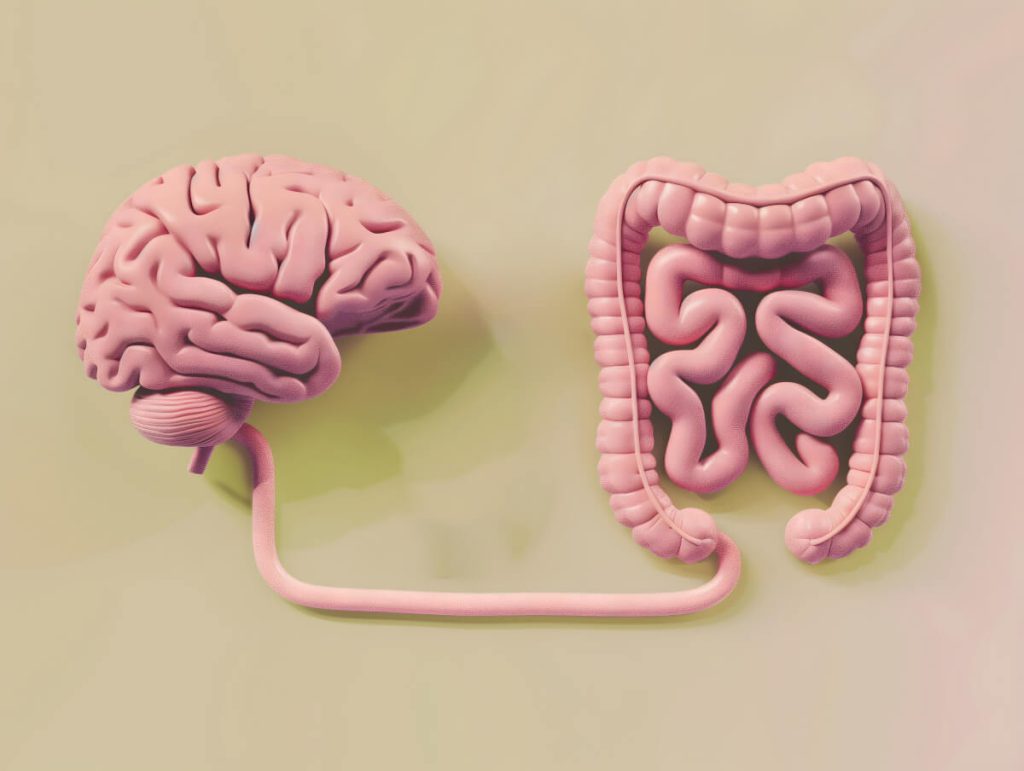

New research shows how a calm mind could start in your stomach, not your head

SINGAPORE — Mental health disorders are on the rise globally, with anxiety affecting millions. While there’s no shortage of prescription medications available for patients, a new study suggests an unexpected ally in the fight against anxiety might be living in our digestive systems.

Scientists from Duke-NUS Medical School and the National Neuroscience Institute of Singapore have discovered that bacteria in our gut produce specific compounds that can influence anxiety-related behaviors. Their research, published in EMBO Molecular Medicine, reveals how these microscopic organisms might help regulate our emotional responses.

“Our findings reveal the specific and intricate neural process that link microbes to mental health,” explains Associate Professor Shawn Je from Duke-NUS’ Neuroscience and Behavioural Disorders Programme. “Those without any live microbes showed higher levels of anxious behavior than those with live bacteria. Essentially, the lack of these microbes disrupted the way their brains functioned, particularly in areas that control fear and anxiety.”

In their research, scientists worked with two groups of mice. One group was raised normally, with all the typical bacteria that live in and on their bodies. The other group was raised in completely sterile conditions from birth, meaning they had no bacteria at all. These were called “germ-free” mice.

To test anxiety levels, researchers used several carefully designed behavioral tests. In one test called the open field test, they placed mice in a large box with both open areas and enclosed spaces. Mice naturally prefer staying close to walls and enclosed spaces when they’re anxious. The germ-free mice spent significantly more time hiding in enclosed areas and made fewer trips into open spaces compared to normal mice.

They also used another test called the elevated zero maze, which looks like a circular elevated platform with some open sections and some sections with walls. Again, the germ-free mice showed more anxious behavior, spending less time in the open sections of the maze.

But the researchers didn’t stop at just observing behavior. They wanted to understand what was happening in the brain to cause these differences. Using specialized techniques, they looked at activity in a brain region called the basolateral amygdala, which helps process emotions like fear and anxiety. They found that brain cells in this region were much more active in the germ-free mice.

Further investigation revealed that this increased brain activity was linked to problems with specific proteins called SK2 channels. These channels normally act like a brake system for brain cells, preventing them from becoming too active. In mice without gut bacteria, these channels weren’t working properly, leading to overactive brain cells.

To confirm their findings, the researchers tried two different treatments. First, they gave some germ-free mice normal gut bacteria. Second, they added a compound called indole, which is normally produced by gut bacteria, to the drinking water of other germ-free mice for six weeks. Both treatments helped normalize brain cell activity and reduced anxiety behaviors.

The results were exciting: mice that received either treatment began spending more time exploring open spaces and showed significantly less anxious behavior overall. Their brain activity patterns also became more similar to those of normal mice.

These findings are particularly interesting because they provide a clear connection between gut bacteria and brain function. Even more importantly, they suggest that bacterial products like indole might offer new ways to help reduce anxiety without using traditional anti-anxiety medications.

“Our findings underscore the deep evolutionary links between microbes, nutrition and brain function,” says Professor Patrick Tan, Senior Vice-Dean for Research at Duke-NUS. “This has huge potential for people suffering from stress-related conditions, such as sleep disorders or those unable to tolerate standard psychiatric medications. It’s a reminder that mental health is not just in the brain–it’s in the gut too.”

Paper Summary

Methodology Breakdown

Researchers used male C57BL/6J mice, comparing those raised in germ-free conditions to normal controls. They conducted behavioral tests including open field exploration and elevated zero maze tests to assess anxiety-like behaviors. Brain activity was measured through c-Fos expression (a marker of neuronal activity) and detailed electrophysiological recordings of neurons in the basolateral amygdala.

Results

Germ-free mice showed significantly increased anxiety-like behaviors, spending less time in open areas and making fewer transitions between spaces. Their BLA neurons displayed hyperexcitability and altered SK channel function. Treatment with either live bacteria or indole normalized both neuronal activity and behavior.

Limitations

The research was conducted exclusively in male mice of one specific strain, potentially limiting generalizability. Additionally, the exact mechanism by which indole influences SK channels remains to be fully elucidated. Human applications would require extensive additional research.

Discussion and Takeaways

This study provides concrete evidence for a molecular mechanism linking gut microbiota to anxiety-related behaviors through SK channel regulation in the amygdala. The findings suggest potential therapeutic strategies using either probiotic bacteria or their metabolites like indole.

The research team is now planning clinical trials to determine whether indole-based probiotics or supplements could effectively treat anxiety in humans. This could represent a significant advancement in mental health treatment, offering a natural alternative or complement to traditional anxiety medications.

Research Support

The research was supported by various institutions including Singapore Ministry of Education, National Medical Research Council, and Duke-NUS Medical School. The authors declared no competing interests except for one author’s position on an editorial board.

Publication Details

The study appeared in EMBO Molecular Medicine in February 2025, representing a collaboration between Duke-NUS Medical School and the National Neuroscience Institute of Singapore. Authors: Weonjin Yu, Yixin Xiao, Anusha Jayaraman, et al., DOI: 10.1038/s44321-024-00179-y