ESA

ESAThe mysterious force called Dark Energy, which drives the expansion of the Universe, might be changing in a way that challenges our current understanding of time and space, scientists have found.

Some of them believe that they may be on the verge of one of the biggest discoveries in astronomy for a generation – one that could force a fundamental rethink.

This early-stage finding is at odds with the current theory which was developed in part by Albert Einstein.

More data is needed to confirm these results, but even some of the most cautious and respected researchers involved in the study, such as Prof Ofer Lahav, from University College London, are being swept up by the mounting evidence.

“It is a dramatic moment,” he told BBC News.

“We may be witnessing a paradigm shift in our understanding of the Universe.”

The discovery of Dark Energy in 1998 was in itself shocking. Up until then the view had been that after the Big Bang, which created the Universe, its expansion would slow down under the force of gravity.

But observations by US and Australian scientists found that it was actually speeding up. They had no idea what the force driving this was, so they gave it a name signifying their lack of understanding – Dark Energy.

DESI

DESIAlthough we don’t know what Dark Energy is – it is one of the greatest mysteries in science – astronomers can measure it and whether it is changing by observing the acceleration of galaxies away from each other at different points in the history of the Universe.

Several experiments were built to find answers, including the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) at the Kit Peak National Observatory near Tucson Arizona. It consists of 5,000 optical fibres, each one of which is a robotically controlled telescope scanning galaxies at high speed.

Last year, when DESI researchers found hints that the force exerted by dark energy had changed over time, many scientists thought that it was a blip in the data which would go away.

Instead, a year on, that blip has grown.

“The evidence is stronger now than it was,” said Prof Seshadri Nadathur at the University of Portsmouth

“We’ve also performed many additional tests compared to the first year, and they’re making us confident that the results aren’t driven by some unknown effect in the data that we haven’t accounted for,” he said.

‘Weird’ results

The data has not yet passed the threshold of being described as a discovery, but has led many astronomers, such as Scotland’s Astronomer Royal, Prof Catherine Heymans, of Edinburgh University, to sit up and take notice.

“Dark Energy appears to be even weirder than we thought,” she told BBC News.

“In 2024 the data was quite new, no-one was quite sure of it and people thought more work needed to be done.

“But now, there’s more data, and a lot of scrutiny by the scientific community, so, while there is still a chance that the ‘blip’ may go away, there’s also a possibility that we might be edging to a really big discovery.”

ESA

ESASo what is causing the variation?

“No one knows!” Prof Lahav admits, cheerfully.

“If this new result is correct, then we need to find the mechanism that causes the variation and that might mean a brand new theory, which makes this so exciting.”

DESI will continue to take more data over the next two years, with plans to measure roughly 50 million galaxies and other bright objects, in an effort to nail down whether their observations are unequivocally correct.

“We’re in the business of letting the Universe tell us how it works, and maybe it is telling us it’s more complicated than we thought it was,” said Andrei Cuceu, a postdoctoral researcher at the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, in California.

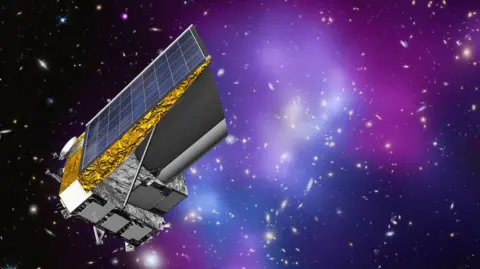

More details on the nature of Dark Energy will be obtained by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Euclid mission, a space telescope which will probe further than DESI and obtain even greater detail. It was launched in 2023 and ESA released the new images from the spacecraft today.

The DESI collaboration involves more than 900 researchers from more than 70 institutions, around the world, including Durham, UCL and Portsmouth University from the UK.