Aldeman: In the 2023-24 school year, public schools added 121,000 employees, hitting a record high, even though enrollment dropped by 110,000

By Chad Aldeman

This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

Public schools added 121,000 employees last year, even as they served 110,000 fewer students.

This is a continuation of recent trends. In per-student terms, public schools have hit new all-time staffing highs in each of the last three years.

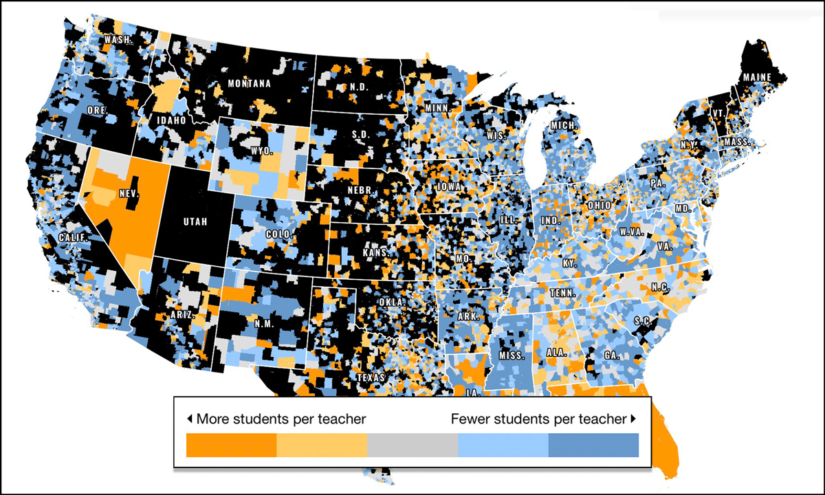

The 74’s art and technology director, Eamonn Fitzmaurice, and I have been following these trends and mapping out how they’re changing across the country. We’ve now updated our charts through the 2023-24 school year. Click on the map below to see what’s happening in your community.

Student/Teacher Ratio Growth

As in previous years, we screened out very small districts and those without sufficient data (marked in black). That allowed us to examine staffing and enrollment trends for over 9,500 districts, comprising 92% of K-12 students nationwide. We then compared the teacher and student counts from 2023-24 — the most recent available — with the same figures for 2016-17.

About one-quarter of districts had fewer teachers per student last year than they did seven years earlier. Those are shaded in orange or yellow. Districts in Alaska, Nevada and especially Florida are predominantly orange on the map, meaning they have higher student-to-teacher ratios than they did before the pandemic.

But many more districts are shaded blue or gray, meaning they serve fewer — or a lot fewer — students per teacher than they did seven years earlier. Overall, three-quarters of districts fell into one of these categories.

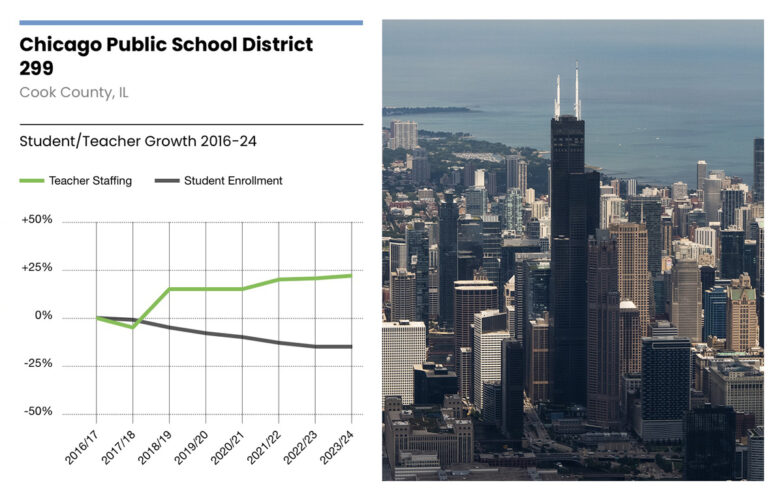

At the most extreme are places where student enrollment declined while the district added staff. There were almost 3,000 districts in this category. Chicago, for example, lost 55,000 students while adding 4,200 teachers. Fairfax County, in Virginia, lost 7,000 students but added almost 700 new teachers.

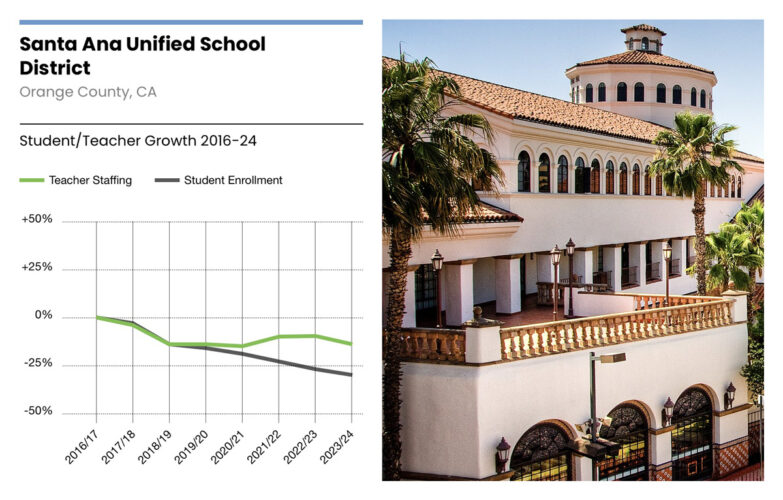

Slightly less extreme are districts that shrunk their staff counts, but not as fast as they lost students. For example, Santa Ana Unified in California reduced its teacher count by 14%, but it suffered a 30% decline in student enrollment. Similarly, San Antonio, Texas, reduced its teacher count by 7% as student enrollment fell 15%.

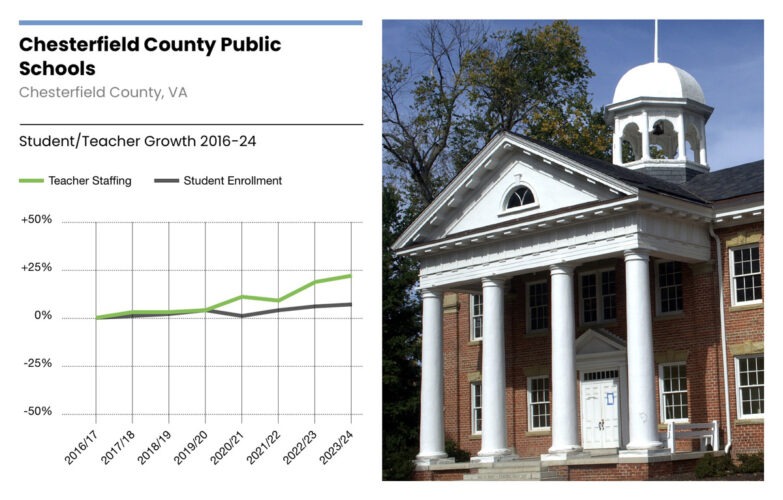

Another group of districts gained students, but they increased their teacher counts even faster. Chesterfield County in Virginia served 7% more students with 22% more teachers. Also in Virginia, Loudon County added 27% more teachers to serve 4% more students.

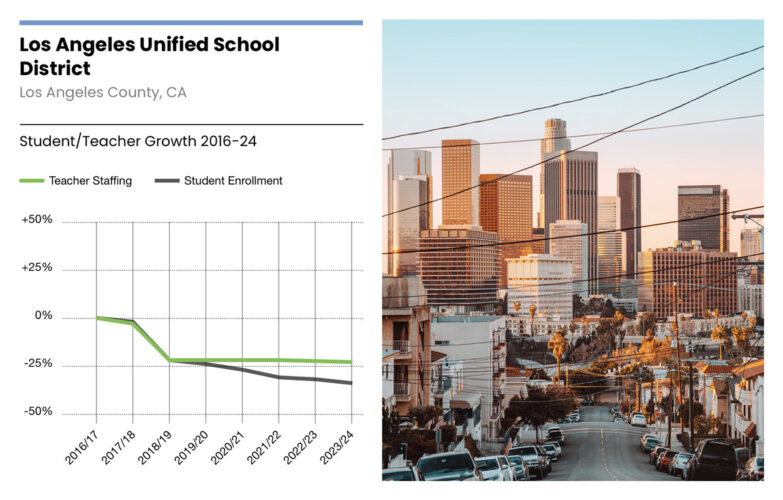

Thanks to an infusion of $190 billion in federal relief funds, schools have been on a hiring spree over the last few years. You can visibly see the effects of the federal money in some of the district charts. For example, before the pandemic, Los Angeles Unified was reducing its teacher count pretty much in line with its declining enrollment. But with the infusion of federal (and state) funds, Los Angeles kept staffing levels constant despite further enrollment declines. Gwinnett County in Georgia shows a similar bifurcated trend. Its staffing and enrollment lines were moving in tandem until the federal funds drove a rapid increase in hiring.

Two teams of highly regarded researchers found that the federal funds helped boost student achievement, and the staffing gains are surely part of that story. But policymakers should be worried that the elevated hiring levels won’t be sustainable without new investments.

As a hypothetical, I looked at what might happen if districts were forced to go back to the staffing ratios they had in 2018-19. In that scenario, public schools across the country would need to lay off the equivalent of 156,000 teachers (512,000 staff members overall). Large districts like New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Gwinnett County, Dallas and Philadelphia would all need to lay off 10% or more of their teaching staff.

Cuts of this magnitude are not on the immediate horizon. State investments in public education continued to grow last year, and many districts were able to build up their reserve funds or frontload some purchases like textbooks or equipment over the last few years. Tapping into those savings might allow some districts to temporarily stave off painful cuts.

But a paper from the Calder Center looked at district budget expenditures to estimate how many educator jobs were funded solely by federal COVID aid. They found that, in Washington state alone, roughly 8,400 teachers were hired with the federal funds.

Now that that money is gone, thousands of educators’ jobs are at risk. Districts will either need to reduce staff counts or find other ways to pay them.