Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – Two years ago, MIT literature professor Arthur Bahr experienced a remarkable day at the British Library, where he had the opportunity to examine the Pearl-Manuscript.

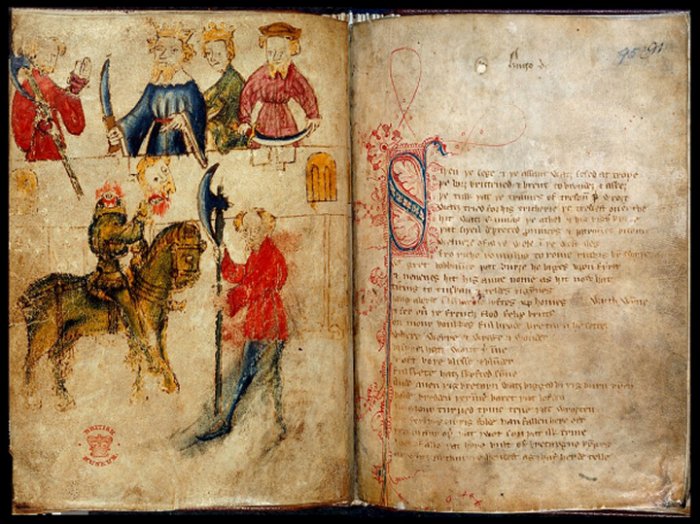

This unique volume from the 1300s contains early versions of significant medieval works, including “Pearl,” “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” and two other poems. Today, “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” is a staple in high school English curricula; however, it might have been lost to history without this manuscript’s preservation. The authorship of these texts remains unknown, but what is evident is that this manuscript is an artistic masterpiece itself, featuring bespoke illustrations and expertly crafted parchment.

The Pearl Manuscript. Credit: Public Domain

Bahr describes the Pearl-Manuscript as extraordinary and unexpected as its contents. Officially known as “British Library MS Cotton Nero A X/2,” this document’s significance extends beyond its literary value.

In his new book, “Chasing the Pearl-Manuscript: Speculation, Shapes, Delight,” published by the University of Chicago Press this month, Bahr delves into both its textual content and physical attributes. Utilizing technologies like spectroscopy alongside traditional examination methods has allowed Bahr to uncover some of its hidden secrets.

“My argument is that this physical object adds up to more than the sum of its parts, through its creative interplay of text, image, and materials,” Bahr says in a press release. “It is a coherent volume that evokes the concerns of the poems themselves. Most manuscripts are constructed in utilitarian ways, but not this one.”

Bahr was first introduced to “Pearl” during his undergraduate studies at Amherst College, in a course led by medievalist Howell D. Chickering. The poem is a complex exploration of Christian ethics, featuring a narrative where a grieving father dreams of conversing with his deceased daughter about the meaning of life.

“It is the most beautiful poem I have ever read,” Bahr says. “It blew me away, for its formal complexity, and for the really poignant human drama.” He adds: “It’s in some sense why I’m a medievalist.”

Bahr’s first book, “Fragments and Assemblages,” explores how medieval bound volumes often comprised diverse documents, making it a natural progression for him to apply this analytical approach to the Pearl manuscript. While most scholars believe the Pearl manuscript was crafted by a single author, certainty eludes us. The manuscript begins with “Pearl” and is followed by two other poems, “Cleanness” and “Patience,” concluding with the haunting tale of courage and chivalry, “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” set in King Arthur’s possibly fictional court.

In his book, Bahr identifies thematic connections among these four texts, examining how they form a cohesive yet imperfectly layered whole over time. These links include broad themes such as recurring challenges to speculative thought; each work is replete with paradoxes and dreamlike scenarios that challenge readers’ interpretive skills.

Additionally, there are structural alignments within the texts. Both “Pearl” and “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” contain 101 stanzas each. The numerical structure of “Pearl” revolves around the number 12; nearly all its stanzas have 12 lines—Bahr suggests this deliberate imperfection mirrors an intentional flaw in a fine rug—and features 36 lines per page. Through personal examination of the manuscript, Bahr identified 48 instances of decorated initials whose creator remains unknown.

As Bahr notes: “The more you look, the more you find.”

Recent discoveries about the Pearl-Manuscript have emerged, thanks to spectroscopy, which has uncovered that the volume initially featured simple line drawings that were later enhanced with colored ink. However, firsthand examination of such texts remains invaluable. This led Bahr to London in 2023, where he was granted an extended opportunity to study the Pearl-Manuscript directly.

Professor Arthur Bahr. Credit: MIT

This experience provided Bahr with fresh insights beyond mere formalities. Notably, he observed that the manuscript is composed of parchment—animal skin—and at a crucial juncture in the “Patience” poem, a retelling of Jonah and the whale’s story, there is a unique instance where the parchment is reversed so that its “hair” side faces up instead of the usual “flesh” side.

“When you’re reading about Jonah being swallowed by the whale, you feel the hair follicles when you wouldn’t expect to,” Bahr says. “At precisely the moment when the poem is thematizing an unnatural reversal of inside and outside, you are feeling the other side of another animal.”

He adds: “The act of touching the Pearl-Manuscript really changed how I think this poem would have worked for the medieval reader.” In this vein, he says, “Materiality matters. Screens are enabling, and without the digital facsimile I could not have written this book, but they cannot ever replace the original. The ‘Patience’ chapter reinforces that.”

Ultimately, Bahr thinks the Pearl-Manuscript buttresses his view in the “Fragments and Assemblages” book, that the medieval reading experience was often bound up with the way volumes were physically constructed.

“My argument in ‘Fragments and Assemblages’ was that medieval readers and book constructors thought in a serious and often sophisticated way about how the material construction and the selection of the texts into a physical object made a difference — mattered — and had the potential to change the meanings of the texts,” he says.

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer