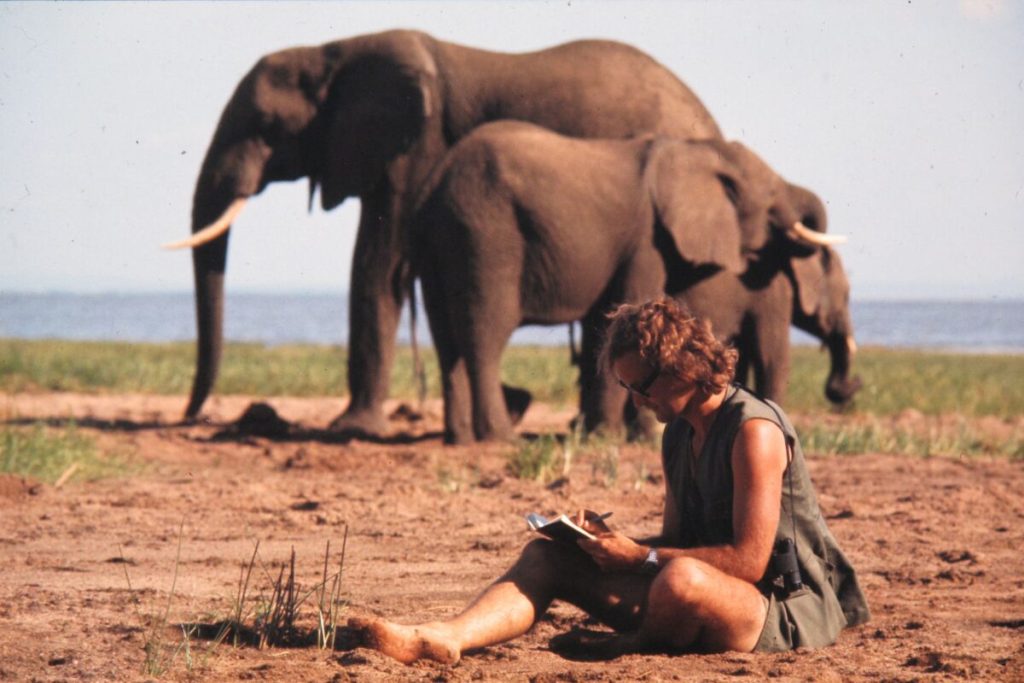

- Iain Douglas-Hamilton spent a lifetime communing with African elephants, going on to champion their conservation during a brutal wave of poaching in the 1970s and 1980s.

- Along with Jane Goodall, he was a pioneer both of studying animals in the field and viewing them as more than objects of study — he recognised elephants as having individual personalities.

- A new film co-produced by the organization he founded, Save the Elephants, also explores how his work challenged the fortress model of conservation.

- The film will be screened at the 2025 DC Environmental Film Festival, for which Mongabay is a media partner.

At this point in history, the hubristic belief that people are above nature has allowed humans to bring immeasurable change to the natural systems that all of life depends upon for survival. The documentary A Life Among Elephants — a collaboration between filmmakers Maramedia, elephant “whisperer” Iain Douglas-Hamilton, his family, and their organization Save the Elephants — could not be more timely.

When Jane Goodall and Iain Douglas-Hamilton sat to compare notes at the start of their careers in the early 1960s, it wasn’t as scientists. Their conversation sprang from their shared and growing wonder at the individuals they were encountering in their work in East Africa. There was a sense of personhood that Goodall saw as she grew to know the chimpanzees she studied, and the elephants that Douglas-Hamilton could have called his family.

Douglas-Hamilton’s work led him to a growing realization that each elephant has personality, individuality, and sentience, Goodall says in A Life Among Elephants. “Iain is devoted to conserving them because he knows each of them as an individual with a life worth living,” she says in the film.

More than simply studying elephants, Douglas-Hamilton spent a lifetime communing with African elephants, before he went on to champion their conservation as a frenzy of poaching took off in the 1970s and 1980s. He knew individual elephants not just by their unique ear profiles or the slant of their tusks. He knew them by their unique personalities, too.

Goodall and Douglas-Hamilton both broke with tradition when they began their studies in East Africa. They did so not just by trading the safe harbor of their well-heeled British lives for the remote African wilderness at a time when most animal studies were done with individuals in captivity.

The two shattered convention because they chose to see their study subjects as individuals with unique personalities, and with personhood. Both scientists gave their subjects names, not neutral numbers. Both drew up biographies of the characters with whom they shared their daily lives. The scientific establishment wasn’t happy about this at the time, but from today’s vantage it’s clear how much both scientists’ approach has changed conventions and attitudes.

When Douglas-Hamilton began his work in the 1960s, it was in an era when fortress-style conservation was widely practiced in its most basic form: designate a protected area, move the people living there out, put up a fence, and keep the people and the animals apart.

But neither people nor elephants can be so easily contained, and elephants and villagers around Tanzania’s Lake Manyara National Park, where Douglas-Hamilton’s work began, came into regular conflict.

Using tracking collars, Douglas-Hamilton was among the first to map the specific, regular trails elephants follow through the landscape. If villagers were encouraged not to settle directly in the animals’ historical paths, he argued, there would likely be less conflict. This work also made a case against corralling elephants, who would only over-browse the landscape if not given a chance to track vegetation naturally.

In essence, Douglas-Hamilton was calling for the dismantling of the fortress model for conservation, an idea that’s gaining wider acceptance today.

“That was the bit of Iain’s work that was probably most prescient. The prevailing view, in terms of how you conserved wild places and wild animals, was that you conserved them through creating protected spaces,” says Nigel Pope, the film’s director. “It’s all about parks and reserves. But you get a species like an elephant, and that concept isn’t really sustainable. At the end of the day, there has to be an element of cohabitation and coexistence.”

The inability to cohabit with elephants is, in Pope’s estimation, as much of a threat to elephant conservation as poaching and hunting.

Both ideas — that elephants have personhood, and that fortress-style conservation fences need to give way to respectful cohabitation — come at a time when it’s never been clearer that humanity needs new ways of engaging with and viewing the more-than-human.

The documentary, which Pope describes as “a legacy film,” isn’t only about Douglas-Hamilton’s life among the elephants.

There are many families who hold the storyline together. Douglas-Hamilton, his partner Oria, and their children Saba and Mara are almost a single organism as they move among the elephant herds in the archival footage, and as they talk about their shared history. Their lives flow in and out of the elephant families whose matriarchs they come to know with deep intimacy.

Another member of this entanglement of lives is fellow conservationist and Save the Elephants field operations director David Daballen, who grew up in northern Kenya, 200 kilometers (120 miles) north of Samburu National Reserve and Save the Elephants’ main research station. As a child, herding cattle, he was intrigued by the elephants he encountered. “Why are there so many together? The love and the care they have for each other, the intelligence they have.”

A chance encounter with Douglas-Hamilton after finishing high school soon found the pair working together. Daballen features prominently in the film and is evidently more than Douglas-Hamilton’s wingman, although they’ve spent many hours in the air together. The two share a close kinship, possibly built around a fulcrum of paternal absence, the filmmakers ponder — both lost their fathers when they were very young — as well as their shared fascination with and love for elephants.

“David’s really exceptional. It’s not accidental that he’s prominent in the documentary. And Iain idolizes him,” Pope says.

It’s clear that Daballen will carry Douglas-Hamilton’s banner forward, and that the respected and politically astute community leader will take the legacy and mission forward.

Through a lifetime of recording how elephant mothers care for their calves, how herds build complex relationships with each other, and how highly sophisticated their level of self-awareness is, Douglas-Hamilton also witnessed the slaughter of intelligent beings whom he knew personally and regarded as family.

In one moving scene, archival footage shows Douglas-Hamilton approaching an elephant skeleton. He immediately identifies it as the remains of an older female, given the size of the cavities where her tusks were moored, and the wear on her teeth.

He reflects somberly on the slaughter of so many “grand old matriarchs who are the memory banks for their families.”

“Families are going to pieces,” he says, his shoulder to the camera, “they’re leaderless. It’s the end of the line, the end game of a huge tragedy playing out across East Africa.”

In spite of this, he is persistent, Jane Goodall reflects in the film. “He doesn’t give up. Even when he finds some of his favorite elephants killed.”

Banner image: Namibian desert elephant. Image by Rhett A. Butler / Mongabay.

Humans are biggest factor defining elephant ranges across Africa, study finds

Tracking imperiled elephants with cutting-edge technology: an interview with Iain Douglas-Hamilton

Feedback: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.