Not quite a household word (beyond academia, anyway), “panopticon” nonetheless turns up in news stories with surprising frequency—here and here, for example, and here and here. The Greek roots in its name point to something “all seeing,” and in occasional journalistic usage it almost always functions as a synonym for what’s more routinely called “the surveillance society”: the near ubiquity of video cameras in public (and often private) space, combined with our every click and keystroke online being tracked, stored, analyzed and aggregated by Big Data.

Originally, though, the panopticon was what the British political philosopher Jeremy Bentham proposed as a new model of prison architecture at the end of the 18th century. The design was ingenious. It also embodied a paranoid’s nightmare. And at some point, it came to seem normal.

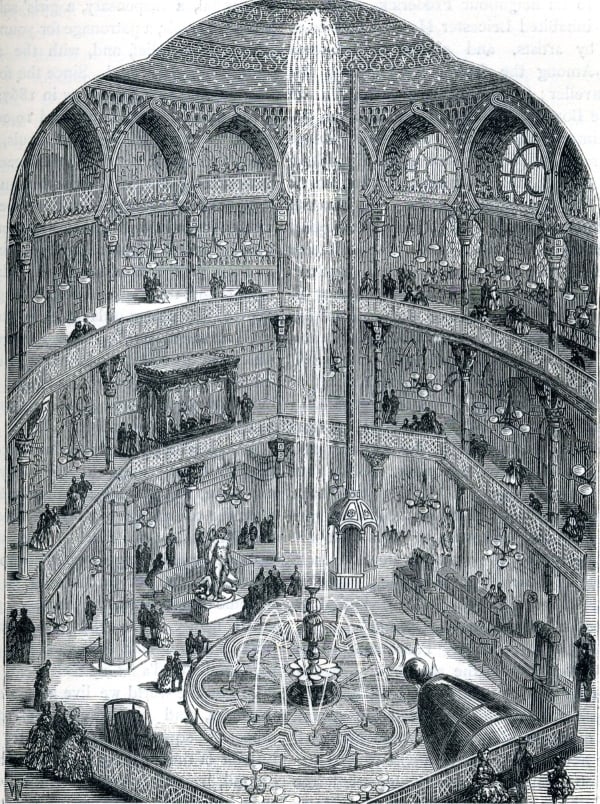

Picture a cylindrical building, each floor consisting of a ring of cells, with a watchtower of sorts at the center. From here, prison staff have an unobstructed view of all the cells, which at night are backlit with lamps. At the same time, inmates are prevented from seeing who is in the tower or what they are watching, thanks to a system of one-way screens.

Prisoners could never be certain whether or not their actions were under observation. The constant potential for exposure to the authorities’ unblinking gaze would presumably reinforce the prisoner’s conscience— or install one, if need be.

The panoptic enclosure was also to be a workhouse. Besides building good character, labor would earn prisoners a small income (to be managed in their best interest by the authorities), while generating revenue to cover the expense of food and housing. Bentham expected the enterprise to turn a profit.

He had similar plans for making productive citizens out of the indigent. The panoptic poorhouse would, in his phrase, “grind rogues honest.” The education of schoolchildren might go better if conducted along panoptic lines; likewise with care for the insane. Bentham’s philanthropic ambitions were nothing if not grand, albeit somewhat ruthless.

The goal of establishing perfect surveillance sometimes ran up against the technological limitations of Bentham’s era. (I find it hard to picture how the screens would work, for instance.) But he was dogged in promoting the idea, which did elicit interest from various quarters. Elements of the panopticon were incorporated into penitentiaries during Bentham’s lifetime—for one, Eastern State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania, opened in 1829—but never to his full satisfaction. He was constantly tinkering with the blueprints, to make the design more comprehensive and self-contained. He worked out a suitable plumbing system. He thought of everything, or tried.

Only in the late 20th century did the panopticon elicit discussion outside the ranks of penologists and Bentham scholars. Even the specialists tended to neglect this side of his work, as the American historian Gertrude Himmelfarb complained in a book from 1968. “Not only historians and biographers,” she wrote, “but even legal and penal commentators seem to be unfamiliar with some of the most important features of Bentham’s plan.” They tended to pass it by with a few words of admiration or disdain.

The leap into wider circulation came in the wake of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975). Besides acknowledging the panopticon’s significance in the history of prison design, Foucault treated it as prototypical of a new social dynamic: the emergence of institutions and disciplines seeking to accumulate knowledge about (and exercise power over) large populations. Panopticism sought to govern a population as smoothly, productively and efficiently as possible, with the smallest feasible cadre of managers.

This was, in effect, the technocratic underside of Bentham’s utilitarianism, which defined an optimal social arrangement as one creating the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. Bentham applied cost-benefit analysis to social institutions and human behavior to determine how they could be reshaped along more rational lines.

To Foucault, the panopticon offered more than an effort at social reform, however grandiose. Its aim, he writes, “is to strengthen the social forces—to increase production, to develop the economy, spread education, raise the level of public morality; to increase and multiply.”

If Bentham’s innovation is adaptable to a variety of uses, that is because it promises to impose order on group behavior by reprogramming the individual.

From a technocrat’s perspective, the most dysfunctional part of society is the raw material from which it’s built. The panopticon is a tool for fashioning humans suitable for modern use.

The prisoner, beggar or student dropped into the panopticon is, Foucault writes, “securely confined to a cell from which he is seen from the front by the supervisor; but the side walls prevent him from coming into contact with his companions.” Hundreds if not thousands of people surround him in all directions. The population is a crowd (something worrisome to anyone with authority, especially with the French Revolution still vividly in mind), but incapable of acting as one.

As if to remind himself of his own humanitarian intentions, Bentham proposes that people from the outside world be allowed to visit the observation deck of the panopticon. Foucault explains, with dry irony, that this will preclude any danger “that the increase of power created by the panoptic machine may degenerate into tyranny …” For the panopticon would be under democratic control, of a sort.

“Any member of society,” Foucault notes, had “the right to come and see with his own eyes how the schools, hospitals, factories, prisons function.” Besides ensuring a degree of public accountability, their very presence would contribute to the panopticon’s operations. Visitors would not meet the prisoners (or students, etc.) but observe them from the control and surveillance center. They would bring that many more eyes to the task of watching the cells for bad behavior.

As indicated at the beginning of this piece, nonscholarly references to the panopticon in the 21st century typically appear as commentary on the norms of life online. This undoubtedly follows from Discipline and Punish being on the syllabus, in a variety of fields, for two or three generations now.

Bentham was confident that his work would be appreciated in centuries to come, but he would probably be perplexed by this repurposing of his idea. He designed the panopticon to “grind rogues honest” through anonymous and continuous surveillance, which the digital panopticon exercises as well—but without a deterrent effect, to put it mildly.

Bentham’s effort to impose inhibition on unwilling subjects seems to have been hacked; the panoptic technology of the present is programmed to generate exhibitionism and voyeurism. A couple of decades ago, the arrival of each new piece of digital technology was hailed as a tool for self-fashioning, self-optimization or some other emancipatory ambition. For all its limitations, the analogy to Bentham’s panopticon fits in one respect: Escape is hard even to imagine.

Scott McLemee is Inside Higher Ed’s “Intellectual Affairs” columnist. He was a contributing editor at Lingua Franca magazine and a senior writer at The Chronicle of Higher Education before joining Inside Higher Ed in 2005.