Most countries spend less than 1% of their national income on foreign aid; even small increases could make a big difference.

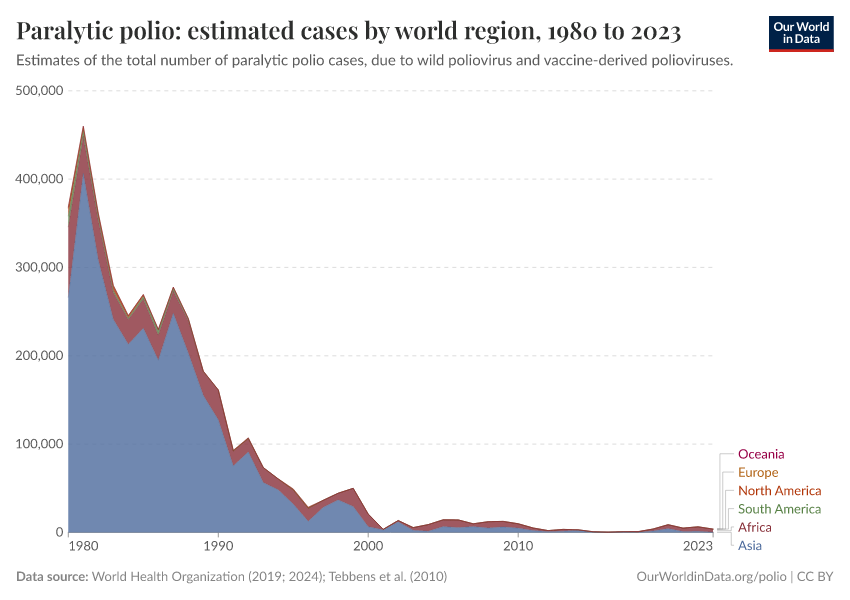

In the early 1980s, almost half a million people were paralyzed by polio every year. Most of them were children. Polio is an awful disease that can cause paralysis within hours and even lead to suffocation and death.

But look at the progress the world has made in the chart below. The number of cases has fallen by more than 99% from its peak.1

In all of 2023, there were the same number of cases as just two days in 1981. Once endemic in almost every country in the world, wild polio is now only endemic in two: Afghanistan and Pakistan.

This has changed the life trajectory of millions of children.

Foreign aid programs have played a crucial role in the fight against polio. In 1998, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative was launched to ensure that all children had access to the polio vaccine.

Even as early as the 1950s, some funding for research into a polio vaccine came from grassroots campaigns and individual Americans giving small donations to find a cure (alongside larger organizations such as the March of Dimes).2 By the late 1980s, several G7 governments and larger philanthropic donors had stepped in to scale up these efforts. The chart below shows the sources of polio eradication funding over time; contributions from foreign governments are shown in red. Note that some of the funding coming from the “multilateral sector” is also sourced from donor countries.

While private donors have made the largest contributions in recent years, governments have played a crucial role over the last few decades.3 In the late 1990s and early 2000s, in particular, donor countries were funding more than 80% of these efforts.

That means that if you live and pay taxes in any of these countries, you have contributed to the amazing progress shown in the chart above.

What’s true for polio is also true for other diseases and essential resources like food. The PEPFAR program — launched by the US in 2003 under George Bush’s administration — is estimated to have saved over 25 million lives from HIV. Donations for bednets and antimalarial treatments have helped reduce the number of people catching and dying from malaria. The Global Fund and USAID have reduced deaths from tuberculosis. Emergency aid has kept people alive during famine and acute food shortages. The list goes on.

These successes have been achieved with a relatively small amount of money. In 2023, the world gave around $240 billion in foreign aid. It’s a very small percentage of most rich countries’ economies. Take the OECD countries combined, and it was just 0.37% of their gross national income (GNI). As you can see in the chart below, Norway is the only country that spends more than 1% of its GNI on aid.4

As a UK citizen, I’m extremely happy for my taxes to be spent this way. I can’t think of anything I’d rather contribute to.

One reason small amounts of funding can have a big impact is that a dollar goes much further in the poorest countries than in the richest. Treatments that many of us might take for granted — like the polio vaccine — often cost as little as a few dollars. For the cost of a takeaway coffee, we could vaccinate several children from potentially fatal diseases.

How can the world achieve more of this?

I feel like I’m in a good position — arguably one of the best positions in history — to help with this in some way. The biggest factor in someone’s opportunities and outcomes is where and when they were born. That is a random lottery. And I happened to get a lucky draw for two reasons.

First, I was born in a rich country, the United Kingdom. Second, I was born at a time and in circumstances that have given me some disposable income and the freedom to choose how to spend it.

That gives me two ways to contribute. First, I can advocate for and put pressure on my government to increase its spending on foreign aid. Second, I can make a personal contribution to some of the most cost-effective charities in lower-income countries.

If you’re in a similar position to me — or have at least one of those options — then there’s something we can do to have a positive impact.

One question you might have is whether most of the world’s aid comes from governments or private donors, which are dominated by billionaire-funded philanthropies. If it’s the former, citizens can have some influence on the global aid budget. If it’s the latter, it’s completely out of our hands.

As the chart below shows, more than 95% of foreign aid came from national governments in 2023. Just under $11 billion — or 4.5% of the total — came from private grants.5

Note that private donors, here, only include contributions submitted to the OECD that meet its criteria for development grants. This is mostly from large philanthropic foundations. It’s not to be confused with total private flows for development, which can include foreign investment, money sent home by migrants, and other forms of private money transfer.

That means two things.

First, a drop in support for aid can have huge consequences for the global total. Let me illustrate this point with some back-of-the-envelope calculations.

The United States gave $62 billion in aid in 2023. If it had cut its aid budget by just 20%, its contributions would have been around $13 billion lower. That would be the same as eliminating all private philanthropic donations worldwide.6

Even reductions in funding from much smaller nations — like my home country, the UK — could have a large impact. “Reform UK”, one of the UK’s right-wing parties, pledged to halve foreign aid in its last manifesto. A halving of foreign aid would have reduced the UK’s contributions by $8.7 billion.7 Again, that’s not far — in relative terms — from the $10.8 billion given by all private donors combined.

Even more recently, the UK prime minister did announce a $6 billion cut to foreign aid by 2027. That’s equal to more than half of all private philanthropic grants.

The second implication is that if we want to see an increase in global foreign aid, building public support for more generous aid budgets from our governments matters a lot. In the next section, I’ll run some numbers to prove this.

We can illustrate this point by focusing on the UN’s target for developed countries to give 0.7% of their GNI to foreign aid.8 Only five countries — Norway, Luxembourg, Sweden, Germany, and Denmark — met this target in 2023.

Let’s imagine that the public in developed countries pressured their governments to step up and meet this target. If all developed countries achieved this, we’d add an extra $216 billion to the pot, meaning the global official development assistance budget would almost double.9 This is illustrated in the chart below. Remember: private donors collectively gave $11 billion in 2023, so this increase would equate to around 20 times as much.

If we take this further and assume that all donor countries were as generous as the most generous country — which, as we saw earlier, is Norway at 1.1% of GNI — the global aid budget would increase to around $700 billion. That means we could deliver up to three times as many polio vaccines, antimalarial bednets, HIV treatments and food packages as we currently do.

Again, it’s important to highlight that these are still relatively small amounts of money for developed economies, just 0.7% or 1.1% of their national income.

Interestingly, this is far less than most people think their countries currently give to foreign aid.

Very recent data is hard to find, but in a 2015 survey, American citizens were asked to guess how much US federal spending goes to foreign aid. The correct answer was just under 1%. Only 3% of respondents got the answer right. The average guess was a whopping 31%. An earlier survey found similar results, with the average guess being 25%.

What’s also interesting is that when asked how much federal spending should be going to foreign aid, the average answer was 10%. That’s ten times more than what is currently spent.

Not all surveys find such a large discrepancy between public perception and reality, but the gaps are still big. In a 2012 survey in the Netherlands, the average guess was that 5.6% of GDP was spent on foreign aid. The correct answer was 0.7%.

So, while “foreign aid” is often the most common answer to questions like, “What sector is the government spending too much on?” some of this might be explained by the fact that most people think we spend far more on foreign aid than we actually do.

As I said earlier, pressuring governments in rich countries to increase foreign aid — or voting for political parties that would — is just one way that I can help move money from the top to the bottom of the global income distribution.

I also donate some of my money directly to the most effective causes. Several years ago, I took the Giving What We Can pledge, committing to give at least 10% of my income to charity. I specifically focus on programs working in some of the lowest-income countries and on causes where small amounts of money can do a lot. The charity evaluator GiveWell is a good resource to find some of the most cost-effective causes to support.

This point on cost-effectiveness is particularly important to me in terms of personal donations, but it also matters when it comes to foreign aid. At the beginning of this article, I highlighted a number of successful aid programs: efforts to eradicate polio, reduce deaths from HIV and malaria, and provide food supplies during famine. It would be great if all aid money were as well-spent as this, but that’s not the reality. Some foreign aid is spent on programs and activities that make little difference. More than half of Brits think that aid is a complete waste due to corruption, and it’s these examples that can often make people sceptical that their dollars are being put to good use.

While I advocate for an increase in the foreign aid budget (and personal donations) overall, I’d also like to see a renewed focus on making sure that we’re spending this money in the best possible way. This would not only improve the outcomes for people who need this support but could also increase support for higher foreign aid budgets in rich countries.

When aid programs work well, they can transform the lives of millions. These programs are not designed to last forever; they’re there to support lower-income countries and kickstart self-fulfilling progress. Unfortunately, these stories of progress are not well-known. If we want to see a resurgence in support for foreign aid, we need to talk about them much more.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Max Roser, Edouard Mathieu, Bastian Herre, Simon van Teutem, and Saloni Dattani for their feedback and comments on this article.

Continue reading on Our World in Data

The global fight against polio — how far have we come?

A generation ago, polio paralyzed hundreds of thousands of children every year. Many countries have eliminated the disease, and our generation has the chance to eradicate it.

Global Inequality of Opportunity

Today’s global inequality of opportunity means that the good or bad luck of where you were born matters most for your living conditions. We look at how this chance factor is the strongest determinant of your standard of living, whether in life expectancy, income, or education.

Foreign Aid

Who gives and receives foreign aid? Which forms does it take? What are examples of when it was (un-)successful?

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie (2025) - “For many of us, it doesn’t cost much to improve someone’s life, and we can do much more of it” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/foreign-aid-donations-increase' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-foreign-aid-donations-increase,

author = {Hannah Ritchie},

title = {For many of us, it doesn’t cost much to improve someone’s life, and we can do much more of it},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/foreign-aid-donations-increase}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.