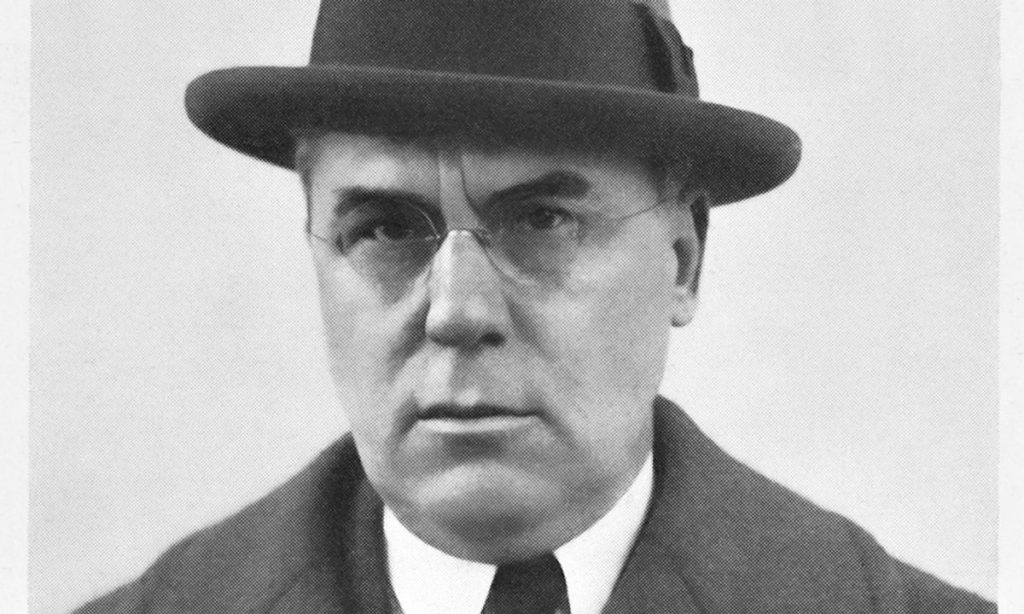

A new biography focused on the life and legacy of the man dubbed America’s first great collector of Modern art, Albert Coombs Barnes, is timely, coinciding with the 100th anniversary of the public opening of the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia this month.

The foundation, established by the stubborn, eccentric pharmaceutical executive in 1922, has one of the world’s best Modern art collections, including 67 works by Paul Cézanne and 59 pieces by Henri Matisse. We spoke to Blake Gopnik about his new book, The Maverick’s Museum.

The Art Newspaper: Why did you decide to write the biography?

Blake Gopnik: There’s nothing I like more than plunging into a really deep archive—an archive that preserves every letter, every taxi receipt, every theatre stub. Barnes wrote a million letters a day and kept all the letters sent to him, often in multiple copies. I learned that all of these documents were preserved in the archive, and no one had ever gotten to them before. It was just too tempting.

Barnes is a fascinatingly complicated figure, an amazing example of an early 20th-century self-made man. He rose from the worst slum in America to become rich—from a treatment for gonorrhoea—and then gave up earning even more riches, to instead collect Modern art.

What were his relationships like? You outline how key men in his life such as William Glackens, his art adviser, and the philosopher John Dewey influenced him.

He could be grotesquely, wildly intemperate. Some of the best letters among his thousands are those he writes to people he doesn’t like or has stopped liking—the letters he writes to Bertrand Russell are hilarious. At the same time, though, he could be incredibly sweet, especially to his dear friend Dewey, one of the most mild-mannered men in the world. He could also be very generous toward people who weren’t like him—gay men, Jewish women and Black people.

He championed Black artists and causes throughout his life. Was he genuinely interested in Black advancement?

There were problems with his support for Black people. It was often condescending; he engaged in stereotypes. But he was also one of the great supporters of Black art and culture. He was present at the party that launched the Harlem Renaissance [at the Civic Club in New York in 1924]. There, this white factory owner [Barnes] gave an important talk arguing that Black art and culture were as great as anything Europe ever turned out, and that African art was as great as anything made by the Greeks or Egyptians.

The first image in the 1937 edition of Barnes’s The Art in Painting book showing works from his collection Special Collections, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia

Has Barnes’s contribution to art history been forgotten?

I discovered that he was one of the most important thinkers about formalism. He wrote a book in 1925 in support of formalism [The Art in Painting], and had a really complicated notion of what formalism was. He wanted formalism to talk about the world. The complexity of his notions of formalism turned out to be a surprise to me, and something I could really sink my teeth into as an art historian. The Art in Painting was hugely influential and read in university classes across America. Alfred Barr, the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), owed it a big debt.

Was he a radical collector?

He began collecting in 1912 when figures such as Van Gogh—Barnes had the first Van Gogh work in America [The Postman, 1889]—still counted as radical. The Burlington Magazine freaked out at the amount Barnes paid for a wonderful, very bold, crazy little Cézanne [Five Bathers, 1877-78]. Barnes is one of the very first people to bring notable Picassos to the United States. They’re pre-Cubist Picassos—they seem relatively safe to us but for him they were absolutely shocking.

Opening the first private museum of modern art in the United States must have had a huge impact?

MoMA in New York didn’t exist yet; it wasn’t founded until 1929. Modernism was still underrepresented, not just in America, but anywhere in Europe, so opening his Barnes Foundation was a radical move, and it was an important move for anyone who cared about art. It was a collection that was supposed to show how art worked. It wasn’t just about elite pleasures.

One of the through lines in the book that I hope people recognise is that Barnes was part of a larger movement, the progressive movement in America, that was prominent at just that moment under President Woodrow Wilson. John Dewey, the superstar philosopher of that era, was one of the great progressives. There was this little window of maybe 20 years when the Gilded Age, an age much like ours, was in question, and people were trying to resolve some of the horrors of unbridled capitalism. Barnes, a deeply committed egalitarian, was right in the thick of it.

Do you like him?

I hate Barnes. And I love him, deeply. And I think that’s how everyone would feel about him and must have felt at the time. Even mild-mannered Dewey loved Barnes deeply but despaired of his friend’s bad behaviour.

There are some very funny anecdotes including a report in The New Yorker that Barnes would put on a workman’s overalls in order to listen in on his visitors at the Barnes Foundation.

Barnes became so famous for his strange behaviour that there was a huge temptation to make up stories that supported that reputation. He actually liked to be thought of as a madman—except when he didn’t. It was always a two-edged sword for him. It’s very hard to know when the stories of his belligerence are true—lots are—and when they’re fabrications he encouraged.

• Blake Gopnik, The Maverick’s Museum: Albert Barnes and His American Dream, Ecco (Harper Collins), 416pp, $35 (hb)