Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

It is a sunny Friday afternoon in South Central Los Angeles, music blasting through the speakers at Figueroa Street Elementary School as nine-year-old Alan runs around the playground with friends, a smile across his face.

“Everyone is very nice to me, and I feel like I belong here,” said Alan, a third grader. “I feel like I am a part of this family.”

In a city with minimal gains in academic achievement and a school district lagging behind the state, this scrappy elementary school stands out.

Nearly all the kids who attend Figueroa come from poor families and many have disabilities or are learning English.

Often kids from such backgrounds struggle in school, but the students at Figueroa Street are making progress.

In reading, the school saw a 14% increase in students in 2024 who met state standards from the previous year. In math, Figueroa saw a 12% jump from the year before.

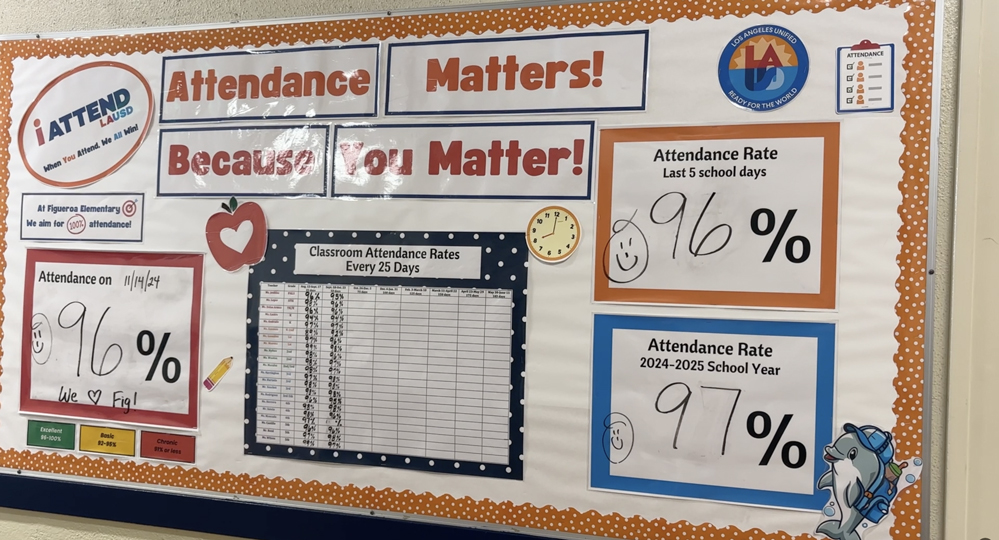

Teachers and students say that’s because everybody in the school is like family. The school achieved a 92% average attendance rate so far this academic year, up from 85% the last year.

This, while the district itself is still crawling out from under sky-high chronic absenteeism rates.

“I think it’s getting people to love their community,” said Principal Shawn Peyatt, who has worked at Figueroa, previously as a teacher, for more than 30 years.

“At the end of the day, school’s a way out,” said Peyatt. “School is going to make a difference.”

Teachers at Figueroa Elementary say the rise in student test scores is linked to school culture.

“People work together well here, and we look out for each other, and it’s nice – you feel supported here,” said Julie Harrington, a third grade teacher, who has been working at the school for 23 years.

“Most of our teachers have been here for many years,” said assistant principal Frank Sanchez. “We’ve all been waiting for the right leader to come on board and just take us there.”

Prior to Peyatt’s leadership, a classroom designated for “emotionally disturbed” students often saw fights that spread to other parts of the school.

“It was a dumping ground for behavior,” said Peyatt. “Really what you were seeing was it was all Black boys, but they weren’t emotionally disturbed. They just probably had some tough times.”

After much back and forth, Figueroa Street Elementary was eventually able to get the district to end the program. Things began to look up.

While in training to become a principal, Peyatt made attendance her top priority, instituting one program after another to keep students in school.

“They say it takes three days to make up one day out, which means you never make-up,” said Peyatt. “Attendance is the first thing.”

During the pandemic, the previous principal, Peyatt and Sanchez viewed themselves as “essential workers,” going to students’ houses if they did not join online classes, delivering chargers, notebooks, pencils and holding fundraisers for families struggling to pay rent.

After an initial dip post-pandemic, the school received $38,000 in funding for attendance improvements and used the money to implement new programs in hopes of getting students back on track.

Working with the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools, an organization that partners with Los Angeles Unified to target high-need schools, Figueroa hired an English and math coach.

Coaches work with teachers, providing feedback on lessons and serving as an extra teaching resource.

The Partnership was first introduced to the school 15 years ago. In addition to teacher training and curriculum development, it serves as a mediator between Figueroa and the school district.

“They gave us the control to be able to bring in our own people, our own teachers,” said Sanchez. “That was a big turning point.”

After the pandemic, the school also created an attendance award system, hosting a pizza party for classes that achieved full attendance and providing students with points towards the school gift shop for good behavior.

If students are absent for two or more days, administrators will go to their house to check on them.

“This year we decided to incentivize parents,” Peyatt said. “We’re doing raffles for parents that have kids of excellent attendance.”

Instead of expecting students to ace every test, teachers look instead for their ability to improve.

Leticia Hurtado, a third-grade teacher at Figueroa, said teachers do this by “allowing [students] to struggle, allowing them to make mistakes.”

The kids know teachers at Figueroa will help them through.

This article is part of a collaboration between The 74 and the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s){if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;

n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window,

document,’script’,’https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘626037510879173’); // 626037510879173

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);