India recorded its warmest February in 124 years this year. The India Meteorological Department has already raised an alarm for March, saying that the month will experience above normal temperatures and more than the usual number of days with heat waves. The period coincides with the beginning of India’s wheat harvest season, and extreme heat poses a grave threat for the country’s second-most consumed crop, after rice.

Wheat in India

In India, wheat is primarily grown in the northwestern parts of the Indo-Gangetic plains. Primary producers include the States of Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, and Madhya Pradesh. Wheat needs a cooler season to grow, and the crop is usually sown between October and December. It is harvested between February and April in the rabi crop season.

The Indian government set a wheat procurement target of 30 million tonnes for the 2025-2026 rabi marketing season, news agency PTIreported in January. The lower procurement target comes despite the agriculture ministry aiming for a record wheat production of 115 million tonnes in the 2024-2025 crop year (July-June), the report added.

In 2024-2025, government wheat procurement was recorded at 26.6 million tonnes. While this exceeded the 26.2 million tonnes procured in 2023-2024, it fell short of the 34.15 million tonne target for the year.

In May 2022, India had prohibited wheat exports. This was shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine, a major wheat-producing country, which disrupted international availability of the food grain and triggered a global price hike.

Heat and wheat

Climate variability itself is not a new phenomenon, but it catches our attention when the crop growth season overlaps with heat wave conditions, Sandeep Mahato of the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF), Chennai, told The Hindu.

A 2022 study in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences noted that increasing global warming is causing heat stress that “triggers significant changes in the biological and developmental process of wheat, leading to a reduction in grain production and grain quality”.

According to the paper’s authors, heat stress is known to affect the growth and development of wheat by altering “physio-bio-chemical processes such as photosynthesis, respiration, oxidative damage, activity of stress-induced hormones, proteins and anti-oxidative enzymes, water and nutrient relations, and yield-forming attributes (biomass, tiller count, grain number and size) upon exposure to temperatures above the optimum range”.

Stages of wheat growth

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, stages of wheat growth are defined based on how different organs of the plant develop. This can be broadly grouped into four stages:

(i) Germination to emergence: This includes the growth of the seed until the seedling breaks through the soil surface and the first leaf emerges.

(ii) Growth stage 1: Steps from emergence to double ridge. Shoots appear, and the plant growth shifts focus from producing primordial leaves to flowering structures called spikelets.

(iii) Growth stage 2: This stage lasts from double ridge to anthesis. This is where the focus of the plant shifts from vegetative to reproductive stage. This is also one of the stages where the plant is comparatively more susceptible to heat stress.

(iv) Growth stage 3: This stage includes the grain-filling period, from anthesis to maturity.

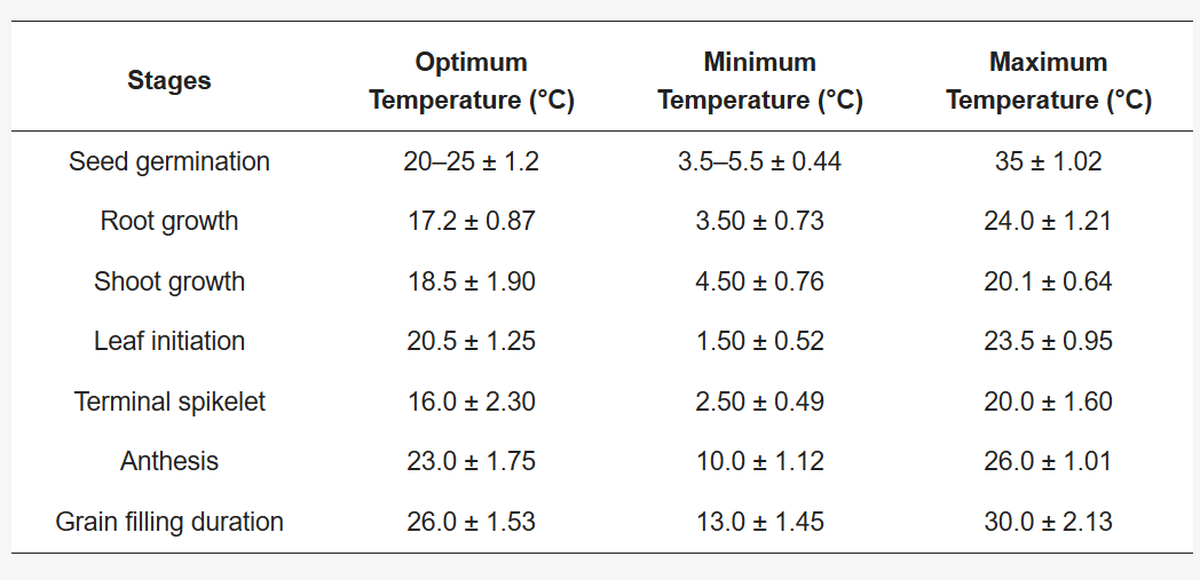

Optimal temperature required for different stages of growing wheat.

| Photo Credit:

DOI: 10.3390/ijms23052838

According to experts, the real problem starts with the oceans. The Indian Ocean is warming at an accelerated rate. A 2024 study conducted by scientists at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, Pune, noted that the Indian Ocean will likely be in a “near-permanent heat wave state” mainly as a result of global warming by the end of the century.

The frequency of marine heat waves is expected to increase tenfold, from the current average of 20 days per year to 220–250 days per year, the study added.

A warming Indian Ocean will in turn alter India’s monsoon, on which most of the country’s agriculture depends. For example, the kharif or summer crop season is starting and ending late, which inevitably delays the beginning of the rabi season.

Wheat is a rabi crop. If its sowing starts late, the later stages of plant growth will coincide with early heat waves in India. February 2025 was warmer than usual, and similar trends have been predicted for March. This is also the peak season for wheat harvest, and ideal temperature in later stages of the plant’s growth should not cross 30º C.

“High temperatures cause early flowering and faster ripening, shortening the grain-filling period. This results in lighter grains with lower starch accumulation, reducing the total wheat output,” Prakash Jha, assistant professor of agricultural climatology at the Mississippi State University, told The Hindu.

“Extreme heat causes wheat to develop higher protein content but lower starch, making the grain harder and affecting milling quality. Farmers may face lower market prices due to reduced grain weight and quality issues,” he added.

Low crop yield also tends to make farmers desperate and result in overuse of fertilisers, fungicides, etc., Nikhil Goveas, lead climate advisor with the Environmental Defense Fund, told The Hindu. “Higher but inefficient use of resources is another cascading effect of heat-stress challenges in crops.”

Adaptation and mitigation

Food security is central to the adaptation and mitigation strategies officials use to lower the heat stress on wheat crops.

“Wheat is … important for farmers because it can be consumed immediately, so part of the produce is always saved for household consumption,” Goveas said.

Farmers rely on older varieties of the crop because accessibility is a challenge, with problems related to the supply chain, costs, etc. Climate-resilient varieties are important, but they are not a silver bullet solution to the challenge, Goveas added: “The problem is a deeper challenge of the climate crisis on our food systems. The earth is getting warmer. We need to think about not just one crop but all crops: get timings right, have our information and weather systems updated with the knowledge of what to expect, and undertake mitigation efforts against the challenges.”

“The larger question here is to be able to guarantee food security,” Mahato of MSSRF Chennai said. “We have to focus on addressing yield gaps. This ties in the issue of efficient management of resources like fertilisers, pest control, etc.”

According to Mahato, immediate policy support to farmers to deal with heat stress effects on wheat can be in the form of compensation, but there are more long term solutions that need to be incorporated into our agricultural practices.

“Changes in agricultural management strategies to support early sowing of crops in areas that are likely to see early heat waves, or introducing improved yield varieties with shorter growth duration are some policy changes that can alleviate heat stress on wheat,” he added. “There is no compromise that can be done on improving production and that should be the central goal to the adaptation question.”

“Policymakers must take a multi-pronged approach, combining scientific research, financial support, technological solutions, and farmer education to protect wheat crops from rising heat stress,” according to Jha. “This includes promoting heat-resistant wheat varieties, adjusting sowing dates, financial support and crop insurance, and weather monitoring and advisories.”

Published – March 10, 2025 06:00 am IST