Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Two very troubling trends are converging on U.S. schools. One is the rising number of students experiencing homelessness. That figure reached 1.4 million last year, as the number of families with children living in homeless shelters or visibly unsheltered nationwide grew by 39%.

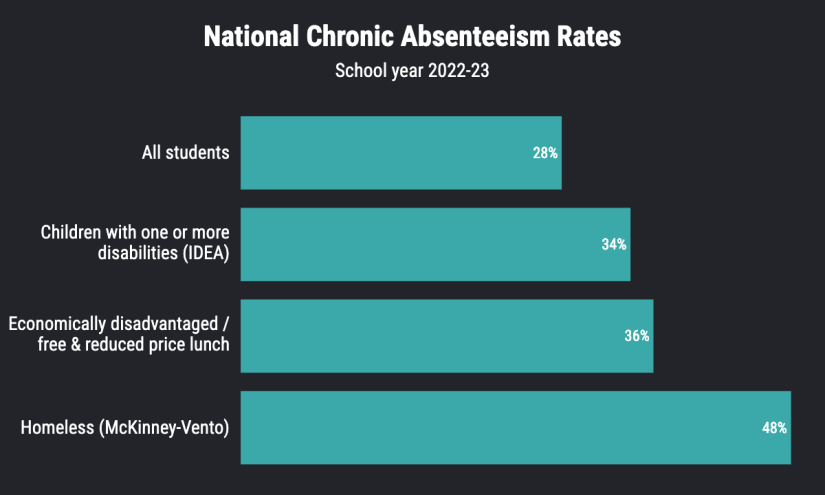

At the same time, schools are struggling to bring down high absenteeism rates that undermine academic achievement and school climate. While there’s been some progress since the pandemic, far more students are missing a month or more of school than in 2019. The rates are particularly high among homeless students: Nearly half of them were chronically absent in the 2022-23, compared with about 28% of all students and 36% of those who are economically disadvantaged.

These results are hardly surprising: The constant moves that come with homelessness often leave children far from their schools and without an easy way to get there. Hunger, lack of clean clothes and mental or physical illnesses complicate the picture.

Our organizations, SchoolHouse Connection and Attendance Works, spent the past six months interviewing school leaders across the country to learn how districts are bringing students without stable housing back to school. Our findings reflect common-sense approaches driven by data and cloaked in compassion.

The first step is to identify the students who need help. The federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act provides school districts with money for transportation, staffing and other assistance to students residing in shelters, cars and motels, as well as those staying temporarily with other people. But many families and youth don’t realize they qualify for extra help from the school district, and others are afraid or embarrassed to say they are homeless.

School districts are adjusting their registration forms to reflect different sorts of temporary living arrangements. And they’re training all school staff, from attendance clerks to counselors to administrators, to recognize the signs of homelessness. Even tardiness or poor attendance can be a tipoff that families have lost their homes.

Some districts are going further. In Henrico County, Virginia, the McKinney-Vento team hosts summer events at Richmond-area motels where homeless families live and signs students up for services. In Albuquerque, team members visit homeless shelters and RV parks.

Once students are identified, districts need to track what’s happening with their attendance and update the data regularly. Many districts are using school attendance teams that focus on addressing the factors that keep students from showing up, such as transportation, hunger and depression.

In California’s Coalinga-Huron Unified School District, for instance, officials huddle at each school once a week with a list of homeless students and review academics, attendance and other indicators. They emerge with action items for helping students, whether it’s rearranging a school bus route, bringing in a counselor or connecting the family to food and other services. Coalinga-Huron’s efforts are supported by real-time data analysis from the Fresno County Office of Education.

In the small rural district and elsewhere, transportation remains one of the biggest barriers to school attendance for homeless students. Recognizing this, the McKinney-Vento Act requires districts to provide eligible students with a way to get to their “school of origin” if it is in their best interest. This often creates logistical challenges.

For students living beyond school bus lines, some districts use vans or car services with drivers vetted for safety. But the costs can be high, and drivers are sometimes in short supply. Others offer gas cards to parents or student drivers. The Oxford Hills School District in Maine paid for one student’s driver’s education course.

The challenges go beyond expenses. Henrico County created school bus stops for homeless children living at motels but found the kids were embarrassed for their classmates to see where they lived. The district then changed the routes so the motels were the first stop of the day and the final stop in the afternoon.

Depression and anxiety can also contribute to absenteeism. Near Denver, Adams 12 Five Star School District matches youth experiencing homelessness with mentors for a 15-hour independent study focused on academic goals, social-emotional development and postsecondary options. Kansas City, Kansas, uses a “2 x 10” approach, with a staff member spending two minutes talking to each at-risk student for 10 consecutive days.

It’s also key to reach families, many of whom report feeling unwelcome at school or embarrassed by their living situations. Fresno Unified School District in California hosts parent advisories to to discuss challenges that are keeping homeless students from attending school. Adams 12 hired a diverse team of specialists whose backgrounds include some of the experiences that their students are living through, including poverty, immigration and homelessness. Henrico County spent some of its federal COVID relief funding for two years of Spanish lessons that help the McKinney-Vento team members communicate with families more easily.

This work takes coordination across departments, so that district staffers who concentrate on homeless students work closely with those monitoring school attendance. It also requires strong relationships with community-based organizations.

Several districts use a community schools approach that coordinates nonprofits and government agencies in supporting students and families. In Coalinga-Huron, where families often have trouble accessing social services located more than an hour away in the county seat of Fresno, the district offers nonprofit organizations space to provide immigration services and language instruction, as well as a food pantry, clothing closet and health clinic.

Several states have also launched grant programs or provide funding specifically for students experiencing homelessness. In Washington state, a grant funds North Thurston Public School’s student navigator program that connects each homeless student with a staff member. Adams 12 relies in part on Colorado’s Education Stability Grant to pay the salaries for some of the specialists on its team.

These districts are using data-driven approaches to improve attendance for homeless students. And they’re doing it with compassion and heart. They recognize that these absences mean weaker academic performance and higher dropout rates. In some places, the absences affect school funding, leaving less money available.

As the homelessness rate continues to rise, districts should adopt these common-sense approaches to identifying students, tracking data and addressing barriers with community, state and federal support.

SchoolHouse Connection and Attendance Works are hosting webinars to explore the findings at 1 p.m. Eastern March 13 and 18. A SchoolHouse Connection-University of Michigan database provides chronic absenteeism rates for homeless students at the district, county and state levels.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Joyce Foundation and Overdeck Family Foundation provide financial support to Attendance Works and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter