In many countries, a substantial share of aid is spent domestically on hosting refugees, offering student scholarships, and administrative costs.

Much of foreign aid is spent on goods that are shipped overseas: food supplies, medicines, or humanitarian assistance in emergency situations.1

But a surprising amount of what’s reported as foreign aid is not sent abroad; it’s spent domestically. Foreign aid budgets in rich countries can include the costs of hosting refugees, some scholarships to foreign students, and some administrative costs that are spent domestically.2 These domestic expenses are reported by countries to the OECD, which tracks and measures foreign aid allocations, so they are included in the widely quoted aid figures you’ll typically see. We’ll refer to these combined costs as “aid money spent at home”.

In 2023, 22% of total foreign aid for all Development Assistance Committee (DAC) countries was spent at home. The DAC countries are a group of 32 high-income countries; from this point onwards, we’ll refer to them as “rich donor countries”.3

In this article, we’ll look at how aid money spent at home varies across countries and categories, how this has changed over time, and what this means for the amount of money available for support overseas.

So, in 2023, 22% of foreign aid was spent domestically in rich donor countries. That was a record year, both in absolute and relative terms. Domestic spending has more than tripled from $14 billion to $48 billion since 2010. As a share of total aid, it has increased from 10% to 22%.

What was this spending used for? The chart below shows the breakdown. You can see that the largest cost in the last few years has been for hosting refugees. This is mostly because of the increase in refugees from Ukraine following Russia’s invasion. There was also a significant increase in 2015 and 2016 as a result of the Syrian civil war.

While it might seem odd to include domestic spending in a foreign aid budget, there are reasonable arguments for doing so. Hosting refugees, for example, addresses urgent humanitarian needs of foreign citizens who’ve been forcibly displaced, even if the money is being spent at home.

As we explain later, our point is that not all aid money spent at home is “wasted” or “misspent”, but the size of these costs does have consequences for other parts of the aid budget.

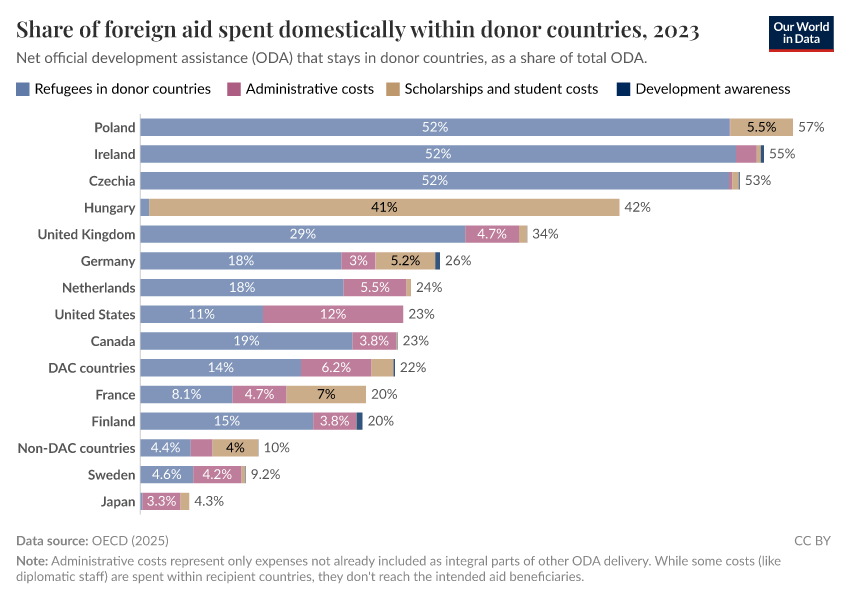

While 22% of foreign aid was spent domestically across all rich donor countries in 2023, spending patterns differed greatly. The chart below shows what share of each country’s total aid was spent domestically on different activities that year.

Three countries spent more than half of their foreign aid domestically. Nearly all of this was spent on hosting refugees, predominantly from Ukraine.

While most other countries spent more overseas than they do at home — which we might expect from “foreign aid” — their domestic share was still substantial. It was more than one-fifth in many countries across Europe and North America. In our home countries, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, it was one-third and one-quarter, respectively.

In nearly all countries, the costs of hosting refugees — and, to a lesser extent, administrative costs — dominate. But there are a few exceptions. Hungary is a clear outlier, with 41% of its aid spent providing scholarships to overseas students.

While most countries include the costs of hosting refugees in their foreign aid reporting, a few countries don’t: Australia and Luxembourg exclude these costs, arguing they don’t help poor countries develop.

The number of refugees looking for protection — and, of course, the number able to make that journey — ebbs and flows depending on geopolitical and humanitarian crises. We might expect 2023 to be an outlier because of the number of Ukrainian refugees seeking safety from the war.

So, was 2023 an anomaly? How has aid money spent at home changed over time?

In the second chart in this article, we saw the absolute amount spent at home over time, including for refugees. This has increased, but so has the total amount spent on aid.

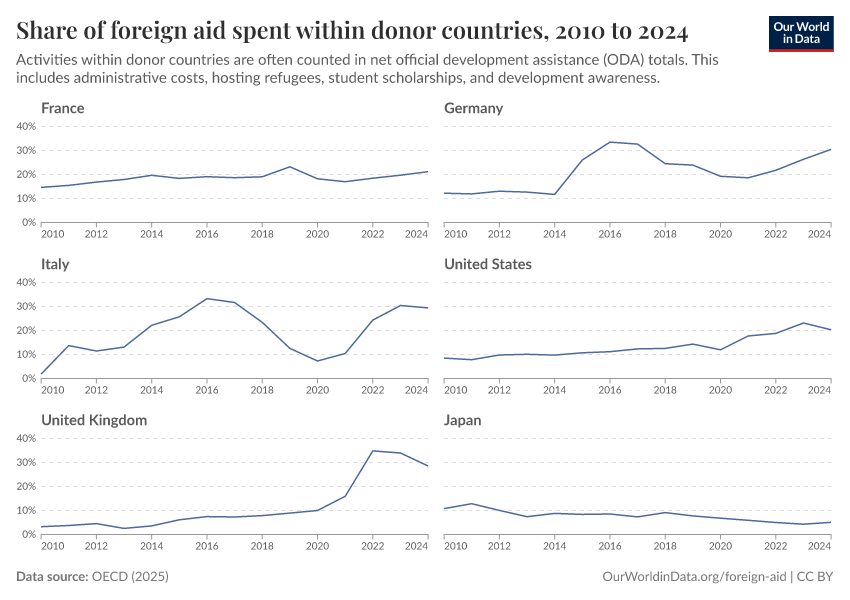

So, let’s look at the change in the share of aid spent domestically. The chart below shows this for a selection of countries.

As mentioned earlier, rich donor countries now spend over 20% of their aid money domestically, but the patterns vary by country. France’s domestic and overseas aid spending has remained fairly stable, unlike Germany, which has seen strong shifts, particularly during the 2010s and the Syrian civil war. Italy’s spending aligns closely with Germany’s.

Domestic spending has increased in the United States in recent years and even more dramatically in the United Kingdom. Japan shows the opposite trend.

As we consider this spending in 2024 and future years, an essential point is that refugee hosting costs only count as foreign aid for the first year. Since most Ukrainians will have been in their host countries for over a year by 2024, these figures could drop sharply.

To be clear, the point here is not that all aid money spent at home is “bad” or “wasteful” and all money sent overseas is “good”. We can think about this in the context of providing aid to a country that has just experienced a humanitarian crisis. There are several ways to help: sending money and resources to the country itself, or spending money on protecting refugees who had to flee those conditions. Both are valuable and worth doing.

However, changes to aid money spent at home affect the amount available for vital and effective programs overseas.

If, for example, the total amount of foreign aid remained constant, an increase in aid money spent at home would inevitably mean reductions elsewhere. If the total aid budget was also increasing — partly to compensate for higher domestic costs — overseas spending could be maintained or even increased simultaneously.

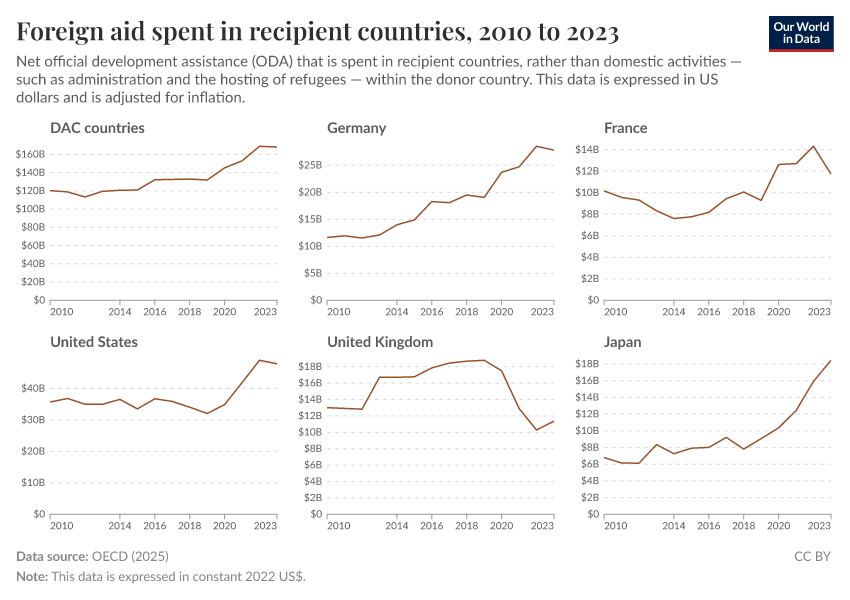

The chart below shows the total amount of aid not spent domestically but sent to recipient countries instead.4 This is both a reflection of each country’s total aid budget and how it’s allocated. For rich donor countries as a whole, the budget has increased by around one-quarter since 2010.5

After a large increase in the overseas budget between 2019 and 2022, it remained the same in 2023.6 Where that money was spent also matters: low-income countries have received slightly less aid in recent years than before the COVID-19 pandemic.

In many countries, the amount spent overseas dropped in 2023: Germany, France, and the United States are examples. The United Kingdom stands out: overseas spending in 2023 was 60% lower than in 2019.

As mentioned earlier, aid money spent at home will likely drop in many countries as refugees are only counted as ODA costs in the first year. This might have increased the amount of spending available overseas in 2024. However, that is unlikely to last with proposed cuts to total aid budgets from leading donors such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany.

In a world that’s more generous, aid activities like hosting refugees do not have to come at the cost of supporting lifesaving programs overseas. But in a world with a shrinking aid budget, this tension will only increase.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Pablo Arriagada, Bastian Herre, Max Roser, and Edouard Mathieu for their feedback and comments on this article.

Continue reading on Our World in Data

Foreign Aid

Who gives and receives foreign aid? Which forms does it take? What are examples of when it was (un-)successful?

For many of us, it doesn’t cost much to improve someone’s life, and we can do much more of it

Most countries spend less than 1% of their national income on foreign aid; even small increases could make a big difference.

The great global redistributor we never hear about: money sent or brought back by migrants

Migrants send or bring back over three times the amount of global foreign aid. Cutting transaction fees could make this support even more effective in reducing poverty.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Simon van Teutem and Hannah Ritchie (2025) - “How much foreign aid is spent domestically rather than overseas?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/foreign-aid-domestic-overseas' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-foreign-aid-domestic-overseas,

author = {Simon van Teutem and Hannah Ritchie},

title = {How much foreign aid is spent domestically rather than overseas?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/foreign-aid-domestic-overseas}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.