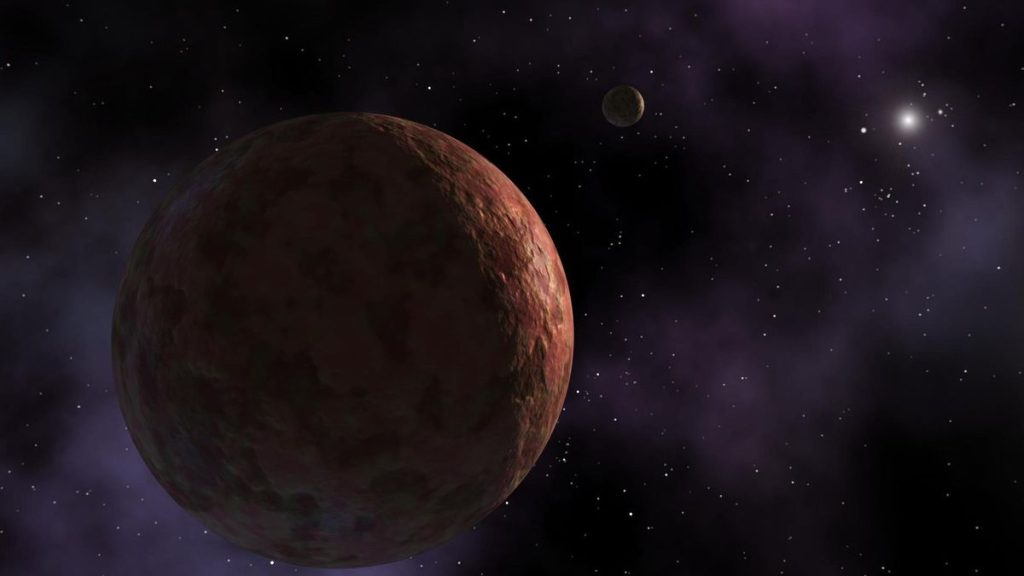

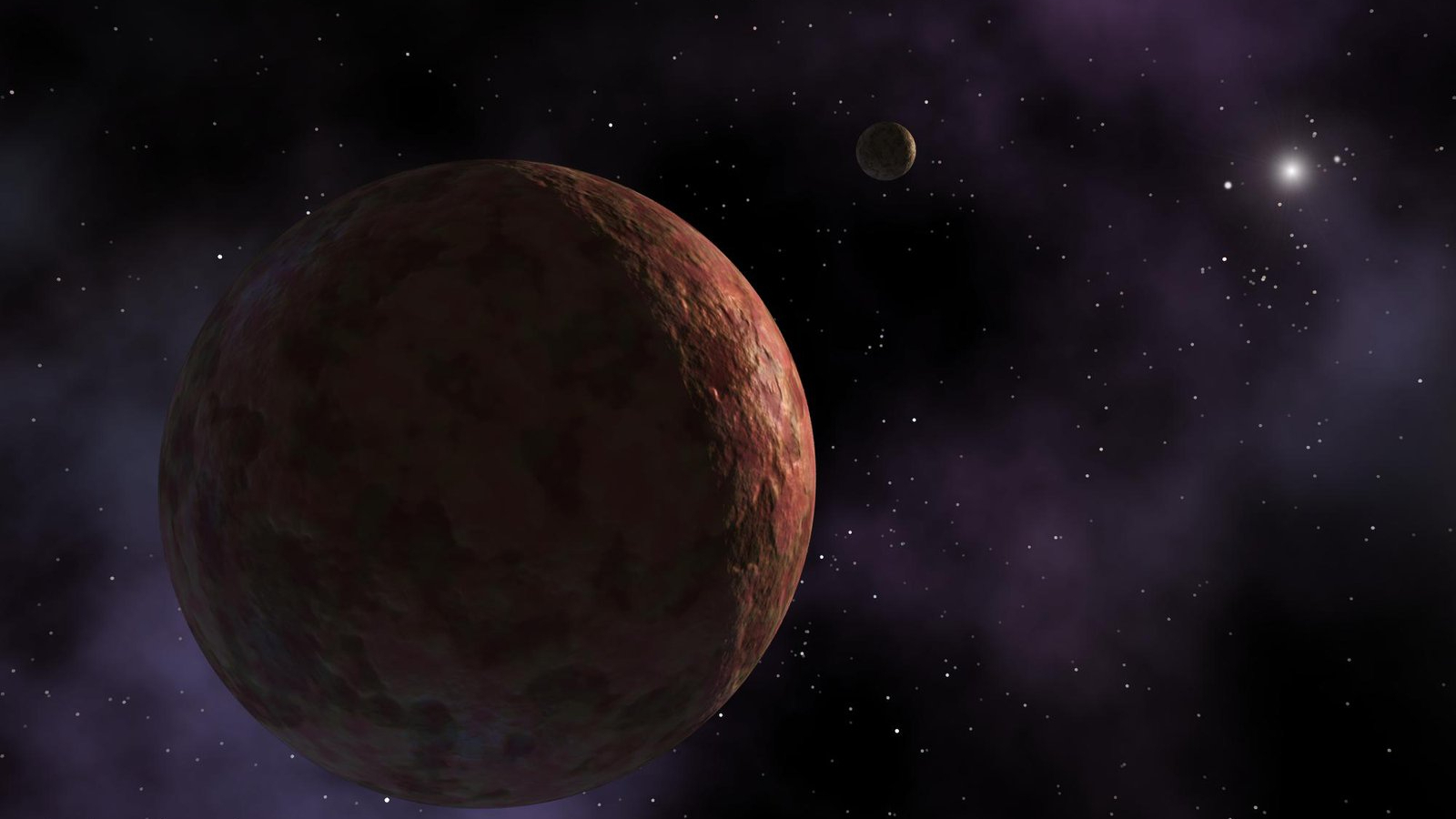

A surprising chemical difference between Pluto and Sedna, another dwarf planet in the distant Kuiper Belt, is helping scientists nail down their respective masses, a new study reports.

The Kuiper Belt is a region in space beyond the orbit of Neptune that’s home to Pluto and most of the known dwarf planets, as well as some comets that are thought to be relics of the solar system’s planet-formation era.

“Kuiper Belt objects are icy worlds [that] can tell us what conditions were like billions of years ago,” explained study lead author Amelia Bettati, a researcher at Elon University in North Carolina. “Studying them helps scientists understand how planets formed and evolved.”

Recent near-infrared spectroscopic studies carried out by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) found that Pluto contains both methane and ethane on its surface, key volatile molecules often found in the outer solar system and thought to be remnants from the time when the planets were forming. Sedna, which is less than half as wide as Pluto, was found to have only methane.

Related: What is the Kuiper Belt?

“We hypothesized that the reason for this difference is that Sedna is much smaller than Pluto, so its gravity is weaker,” Bettati told Space.com. “This weaker gravity allows methane to escape into space over billions of years, while ethane, which is a heavier compound, stays behind.”

While previous studies have identified a general boundary between objects that can hold onto these volatiles and those that cannot, the difference between Pluto and Sedna offers a new clue about how specific escape processes might shape the surface compositions of these distant objects. Sedna, being close to the mass threshold at which volatiles are lost, highlights the importance of understanding how certain chemicals are retained or lost, especially when comparing different Kuiper Belt objects.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

“By studying how methane and ethane escape from Sedna, we calculated how massive Sedna must be to explain its current surface composition,” said Bettati. “To explain the lack of methane but presence of ethane on Sedna, we must raise the minimum mass estimate for Sedna. This is important because it helps refine our understanding of Sedna’s structure and history.”

In their study, Bettati and co-author Jonathan Lunine, of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the California Institute of Technology, modelled the levels of methane and ethane on Sedna. They verified their model’s accuracy using two analogues: Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

Europe’s Rosetta probe studied Comet 67P up close, and NASA’s Cassini spacecraft gathered a wealth of data about Enceladus during the probe’s time in the Saturn system.

“Both objects have well-defined measurements and are outer solar system objects, which justifies considering them analogues,” said Bettati.

To figure out if enough methane and ethane escaped from these objects to no longer show up in their surface spectra, the scientists needed to estimate how much of these chemicals were originally trapped inside.

They did this under two different scenarios. One assumed that the ratio of methane and ethane to water ice is similar to what was measured on Enceladus, while another looked at the ratio found on Comet 67P during the winter. These comparisons helped them understand how much of these compounds may have been lost over time.

“[We used the] Jeans escape model, [which] is a kind of thermal escape driven by the atmospheric temperature, in which the fastest-moving molecules exceed the escape velocity, but the bulk of the molecules do not,” Bettati said.

They also used another model known as hydrodynamic escape, which occurs when the bulk of the molecules are able to escape, rather than just those at the high-velocity end of the distribution. “Much of the atmosphere is in motion, escaping to space,” said Bettati.

The models demonstrated that methane has remained stable on Pluto but escaped from Sedna due to its lower mass. Ethane, however, has stayed stable on both objects, even when using two different outgassing rates — 100% (indicating full release of volatiles) and 10% (a smaller release).

This result aligns with the observed surface spectra and provides a more accurate mass estimate for Sedna. The model also explains the absence of methane on another Kuiper Belt object known as Gonggong.

Related: Our solar system map may need an update — the Kuiper belt could be way bigger

“Like Sedna, Gonggong also lacks surface methane,” said Bettati. “Since Gonggong is similar in size to Sedna, we believe methane must have escaped from it in a similar fashion. This suggests that smaller Kuiper Belt objects lose methane over time, while larger ones, such as Pluto, can hold onto it.

“If scientists know which gases are likely to be present on different Kuiper Belt objects, their loss rates, and their past compositions, they can better plan future missions.”

These findings, in conjunction with JWST observations, will help scientists understand how atmospheres and surface compositions change in the Kuiper Belt and beyond.

“It highlights how JWST is revolutionizing our understanding of the most distant solar system bodies,” Bettati said.

The new study was published in February in the journal Icarus.