When the British artist Tracey Emin was diagnosed with aggressive bladder cancer in 2020 and given six months to live, she wished for two things: a major institutional show in the US and another in Italy. Now both of those dreams are coming true, with I Loved You Until the Morning at the Yale Center for British Art in Connecticut, her first institutional show in the US (opening 29 March), and Sex and Solitude at the imposing Renaissance era Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, her debut museum exhibition in Italy.

Speaking ahead of the Florence show, which opened to the public this week, she says: “It doesn’t get better than this: the architecture, the city, everything. This is it.”

Sex and Solitude is neither a survey nor a retrospective, but it nonetheless spans Emin’s entire career and includes virtually every media she has worked in: appliqué, needlework, neon, monoprint, painting, bronze. It even features the room she locked herself in to paint naked for three and a half weeks (the length of her menstrual cycle) in 1996. Three of her video works are on show nearby in the Gucci Garden’s small, red velvet-upholstered cinema.

Tracey Emin’s I Followed You To The End (2024) in the courtyard at the Palazzo Strozzi

Photo: Ela Bialkowska, OKNO Studio © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2025

Emin has been labelled by the UK press the “enfant terrible” of the British art scene for drunkenly storming out of a live television debate in the late 1990s, among other escapades. Today she is sober (“I haven’t had a drink for five years”) and was last year awarded a damehood—a distinction she is still getting used to, particularly given her past outspokenness. “There aren’t many people from my kind of background that have been made dames,” she says. “But to be given that accolade and to have lived exactly how I’ve wanted to live is quite an achievement.”

If there is a hangover in the British psyche relating to the Emin of the 1990s, in Italy, she is undoubtedly known first and foremost for her art. The artist thinks Italians are more open-minded about her and her work, too, even under a far-right government which recently ignited a row over safe abortions in the country. “Here they judge me for the integrity of my work and where it comes from, because it’s about suffering,“ Emin says. Referencing the abundance of religious and Renaissance art in the city, she says: “it’s in their nature to be emotional. There’s no stiff upper lip in Florence. It feels very liberating for me.”

Florence and its long history as a Renaissance centre for bronze sculpture particularly resonates with Emin, who took her cue from Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise at the Florence Baptistery when creating the bronze doors for the recently renovated National Portrait Gallery in London. Several of her large-scale bronze sculptures, which conjure the lines of Egon Schiele and the forms of Auguste Rodin, are dotted throughout the Strozzi exhibition, including one shown last year at White Cube Bermondsey, I Followed You to the End (2024), which was winched into the palazzo’s internal courtyard in the dead of night to avoid disruption to Florence’s already tourist-laden streets.

Installation view of Sex and Solitude at Palazzo Strozzi, with several of Tracey Emin’s bronze sculptures

Photo: Ela Bialkowska, OKNO Studio © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2025

Emin has shown several times in Italy, with the Roman gallery Lorcan O’Neill and at the Venice Biennale in 2007 when she became the third woman to represent Britain. Her British pavilion presentation was a mixture of existing works—appliqué blankets, drawings and neons—as well as some newer paintings. But Emin wishes she had had the confidence to show a series of large-scale canvases she had been working on. “I had a show at Gagosian [in Los Angeles] at that time, so lots of my big paintings went there. It was a mistake; I should have shown them in Venice,” she says. Emin describes Larry Gagosian as a “brilliant art dealer”, though she says it would have been “too complicated” for her to have worked with both him and Jay Jopling at White Cube in London. Her peer Damien Hirst famously tried to split his loyalties between the two. “I think that probably put me off,” Emin says.

Painting is now at the forefront of Emin’s practice—though the artist’s relationship with the medium has ebbed and flowed throughout her career. She studied painting at the Royal College of Art in London in the late 1980s but abandoned the medium when she had two pregnancies and two abortions in the early 1990s, a time when painting also fell out of fashion among young artists.

“When I was pregnant, the smell of oil paints and terps made me physically sick; it’s like poison,” she recalls. After the abortions, a sense of guilt overtook her. “For the record I’m very pro-choice, but just because you’re pro-choice it doesn’t mean that if you’ve had an abortion, you don’t experience stuff,” Emin says. Her approach to her work changed, she says. “I stopped painting because I had this realisation of the essence of being. After that I couldn’t justify painting, because I felt guilty and weird and fucked up over it all.”

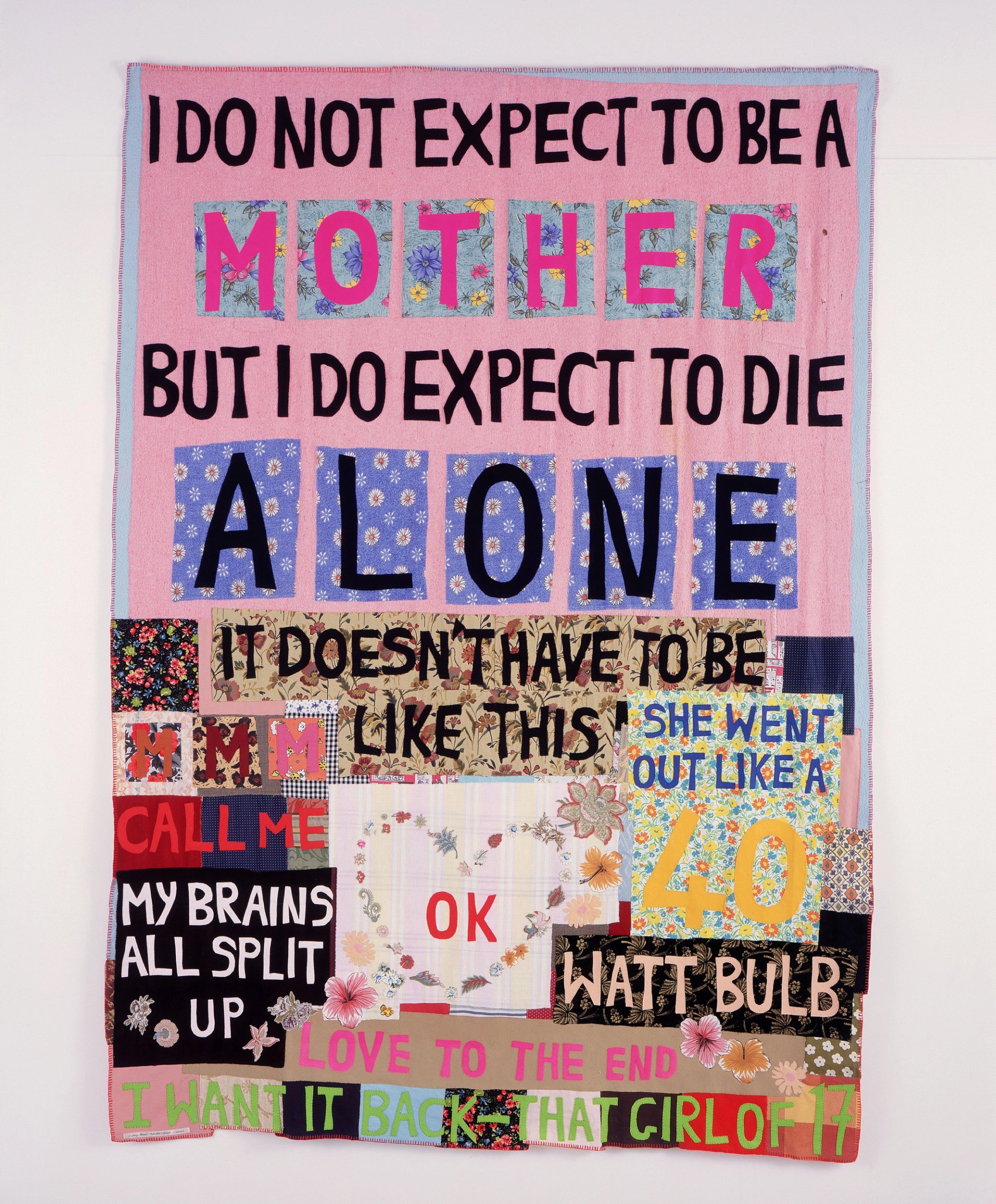

As painting fell away, appliqué became prevalent in Emin’s practice; the artist has said that the process of building up layers and textures in her blankets is very much like painting. Among the textile works on show at the Strozzi is I do not expect (2002) which—with phrases such as “I don’t expect to be a mother but I do expect to die alone” stitched into it—made clear early on Emin’s thoughts on motherhood.

Tracey Emin, I do not expect (2002)

© Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Photo © Stephen White. Courtesy White Cube

“I didn’t think I was going to be a mum because I never had anyone to have children with and I didn’t want to do it on my own,” she says. “Also, I’m so selfish in terms of either doing one thing or another: I’d have either only been a mum and not an artist, or I’d have been a really bad mum. I could never see myself being compromised. As I’ve got older, I realise that I do what I want all the time, I don’t have to sacrifice my time.”

In 1996, Emin created Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made as a way of returning to painting. For the work, Emin locked herself naked in a room at a gallery in Sweden, and created paintings and drawings that appropriated works by male artists including Egon Schiele, Edvard Munch, Yves Klein and Pablo Picasso.

The exhibition includes a recreation of Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made (1996)

Photo: Ela Bialkowska, OKNO Studio © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2025

Her creative director Harry Weller has described the performance as the work that made Emin the artist she is today. “That was the beginning of [her] painting,” he tells The Art Newspaper, though it would be another five years before she embraced painting again.

At the time, Emin had no intention of maintaining the space in which she performed Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made and had planned on burning the contents of the room, but the gallery had other ideas and sold it in its entirety as an installation. It has since been sold at auction twice, for £108,250 in 2001 and £722,500 in 2015, and now resides in the Farschou Foundation’s collection in New York. “I never benefited from [the work] financially, but I was never supposed to, because I was going burn it,” Emin says. “But it doesn’t matter, and it’s here in Florence today.”

Fresh feelings

Sex is one of the enduring and major themes of Emin’s work and is sometimes presented as a force that has the power to cancel out her creative flow. One painting on show at the Strozzi from 2020 reads: “I WANTED YOU TO FUCK ME SO MUCH I COULDN’T PAINT ANYMORE.” Emin says she still wanted to have sex for a period after her cancer diagnosis, but that urge has since gone. “I don’t have any libido, I haven’t for ages,” she says. “I did after the cancer, in the beginning, but now I don’t. I also had a hysterectomy and half of my vagina cut away. Then on top of that, I’m nearly 62 and I’m looking at other things and feeling other things. I feel love, I feel warmth, I feel millions of cuddles. I’m so focused on my work and it’s going really well. I’m the most content I’ve ever been in my life. I feel like I’m doing the right thing.”

Her views on being on her own—solitary, not lonely—have also changed as Emin has got older. Her move to Margate during the pandemic and the subsequent launch of TKE Studios in the Kent seaside town has created a newfound sense of belonging.

“I’m surrounded by the best people I’ve ever been surrounded by in my life, they are all very straightforward and don’t fuck around, I love it,” she says. “Having a big studio makes a difference, I’m much freer—freer to make mistakes, too.” Helping other art students and young artists through her studios has also proven rewarding.

“Putting my money where my mouth is, and not in a saintly way but in a practical way, is a good feeling,” Emin says. “I feel good about lots of things, especially my cats Teacup and Pancake. I can’t explain the amount of pleasure they give me. It’s the small things and the big things. It all just feels really good.”

- Tracey Emin: Sex and Solitude, Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, until 20 July