The firing of possibly thousands of people working in U.S. health agencies this past week is likely to ripple across the biomedical ecosystem, affecting basic scientific research and disease tracking to regulatory oversight of new products.

Enacted by the Trump administration, the layoffs affected a wide range of agencies under the HHS. The exact number of affected employees at each HHS agency isn’t clear, and a department spokesperson declined to provide details. Reports have indicated up to 5,000 staff across HHS may be dismissed, but the actual number could turn out to be lower.

At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, staff cutbacks could weaken the federal government’s monitoring of diseases that affect many Americans, experts said. Layoffs at the National Institutes of Health could curtail the early research that provides the foundation for new medicines in the future.

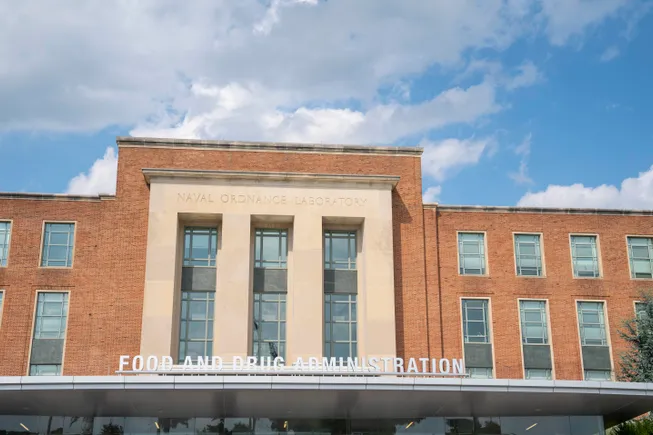

A diminished Food and Drug Administration, meanwhile, could have repercussions for the drug and device industries, as well as hamper oversight of food safety.

“Any place that gets cut, it’s going to have an impact, because there’s not any spare personnel at FDA,” said Robert Califf, a former commissioner under Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden. “I’m very concerned for the public.”

It’s not clear how much the agency’s main drug review offices were affected. “I think it’s pretty accurate that [they] were relatively spared,” Califf said. “That leaves the rest of it.” According to Scott Whitaker, head of the medical device lobbying group Advamed, “at least 230, perhaps more” employees in the FDA office charged with regulating devices were cut.

As with other federal agencies cut by the Trump administration, dismissals were targeted to “probationary” staff — recent hires or long-term employees who were recently promoted — which could impede the FDA’s efforts to expand in newly prioritized areas.

“The cuts at [the] FDA will be terribly harmful for the American people. Indiscriminately firing people because they are new to the agency or new to their current position within the agency makes no sense,” Patti Zettler, a former deputy general counsel at HHS, wrote in an email. “It also disproportionately affects cutting-edge technologies and other areas of focus, like AI and nutrition, in which FDA has been working to increase capacity to meet public health and industry needs.”

A related executive order by President Donald Trump also limits future hiring across the federal government, specifying that agencies can only add one new employee for every four who depart. That policy could impact future staffing and regulatory capacity in many areas affecting public health and drug regulation.

The layoffs and executive orders are part of a campaign that’s being carried out by billionaire Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency, a new service designed to slim down the government and reduce federal spending. While Musk has pledged “radical transparency,” there has been little information made public about how the cuts are being carried out or why they’re targeted to one agency or office versus another.

“Let’s note that there’s no indication that the cuts are done,” said James Shehan, chair of the FDA Regulatory Practice at law firm Lowenstein Sandler.

Other industry experts criticized DOGE’s cuts as haphazard and sloppily implemented.

“I challenge anyone to say that it makes good sense to start [cuts] with your new people and the people who have been promoted,” added Shehan. “If you’re going to cut the fat off a steak, you use a knife. This is like hitting the steak with a sledgehammer, and the possibility that you’re going to render it inedible.”

Kenneth Kaitin, a professor and senior fellow at Tufts University School of Medicine, noted the potential impact on FDA staff’s experience in the future.

“You’re eliminating the learning chain of people who come into the agency,” said Kaitin, who was formerly director of the Tufts University Center for the Study of Drug Development. “You learn in the FDA. There’s a long learning curve and you’re eliminating people at the early stage.”

It’s unclear how widely positions at the FDA funded by industry user fees, such as those authorized under the Prescription Drug User Fee Act, were affected. Those user fee-financed positions are intended to help enable speedy review and approval of drugs and devices.

“It’s hard to actually make sense of why you would make cuts in an area that doesn’t save the taxpayer anything,” said Califf. “It just makes it harder for people to get their work done.”

So far, the pharmaceutical industry and its lobbying groups have been largely quiet. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America declined a request for comment. In a statement, the Biotechnology Innovation Organization said “our ability to protect Americans’ health and our national security, and to drive medical and scientific advances, relies on an ecosystem of innovator companies and government agencies.”

“I’m disappointed they’ve been so quiet,” Califf said. “They’re living in an environment where, if you cross this administration, you’ll likely pay a price.”

Advamed, by contrast, has been more critical, and called for the cuts to be reversed.

“The vast majority of drugs and devices that enter clinical development never make it to market because the risks outweigh the benefits,” he added. “If we don’t have a system that detects that and deals with it, we’ll just recapitulate the whole reason the FDA legislation was put in place to begin with, which is that people were harmed.”

Ned Pagliarulo contributed reporting