In 1984, Fred Ritchin published an article in the New York Times Magazine called “Photography’s New Bag of Tricks,” an early reflection—and warning—on how digital technology would rewrite the rules of image making. Photoshop would not hit the market for several years, and digital imaging at the time required colossally expensive machines. Still, Ritchin saw that these changes in how pictures were made could upend the fields of documentary photography and journalism. Of course, photographs had always been manipulated—for political propaganda, advertising, or artistic experimentation—but now such interventions would become easier to do and more difficult to detect. What would this mean for the photograph’s ability to be a reliable messenger of events as they happened?

Ritchin founded the Photojournalism and Documentary Photography program at the International Center of Photography in New York in 1983. Seven years later, Aperture published In Our Own Image: The Coming Revolution in Photography, his foundational and oft-cited book. He followed that with three more books on the future of image making. Naturally, his attention has recently turned to the vast implications of artificial intelligence on the photographer’s role as credible witness—the subject of his new book, The Synthetic Eye. Here, the photojournalist Brian Palmer talks with Ritchin about the risks and possibilities of AI in a moment already defined by conflict, misinformation, and threats to democracy.

AI-generated image: Taylor Swift appearing to support Donald Trump, 2024

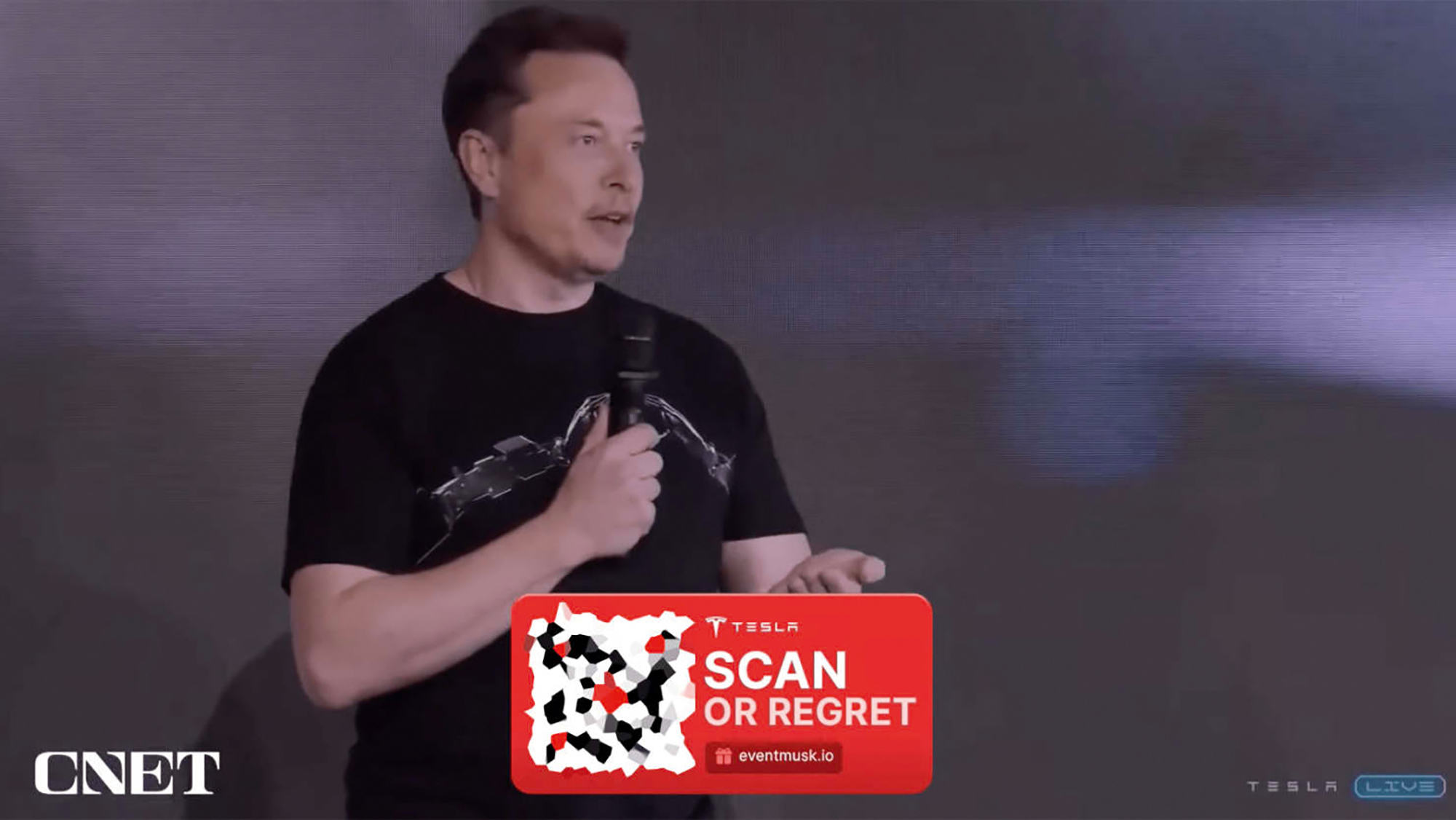

AI-generated image: a deepfake of Elon Musk used in a cryptocurrency scam, 2024

Brian Palmer: Some people argue that the photographic image doesn’t have any credibility anymore. What do interventions with AI mean for documentary photography?

Fred Ritchin: If you have had a visual currency that has been both believable and useful in making the lives of millions of people better, in helping to bring wars to an end earlier, in promoting civil rights, and in provoking global interventions when there’s disease or famine or earthquakes or other serious issues, rather than saying just that it’s been diminished in terms of its credibility, which it has been, I think the appropriate question is: What can be done to restore trust in it as a witness? Some of the responses are technical, many of them involve increased context and authorship as well as collaboration, others involve much more innovative uses of the medium.

And a further question is: How does one now use newer kinds of contemporary imaging, including artificial intelligence, to restore a sense of what’s going on in the world so that we can discuss it and respond with a sense of a shared reality?

Palmer: If I am a young, up-and-coming documentary photographer, why should I care about depicting the world in front of me as opposed to doing something else, using digital technology to create what wasn’t in the frame? Give me some concrete examples, either current or past.

Ritchin: There are many instances from the past in which photography has been used to provoke change in a positive way, and the challenge now is to continue in that tradition of what might be called a constructive illumination.

For example, in 1968 when Eddie Adams made the photograph of a suspected member of the Viet Cong being executed in the street, the following year, a significant portion of American soldiers were pulled out of the war. In 1972, a nine-year-old girl in Vietnam, Phan Thi Kim Phúc, was shown burning from napalm in a photograph by Nick Ut, and the following year the United States pulled out all its soldiers from Vietnam. Both those images—one by an outsider, one Vietnamese—did a great deal to fuel an antiwar movement. The discussion is not simply about photography but about its usefulness as a medium in the world that can at times support positive change and serve as a reference point that people can look at and agree that certain things have been going on.

The photograph has been extremely useful in drawing attention to abuses—the torture of Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib, domestic violence in the United States as seen in the photographs by Donna Ferrato, the drowning of Alan Kurdi while he and his family were trying to escape from Syria in 2015—which may, in fact, be the last iconic photograph capable of provoking the world into a sustained, constructive response.

We’ve increasingly turned photography into a kind of a consumer product. We want to remake the world according to our own perspectives. Now, with artificial intelligence, it becomes even more difficult for a photograph to widely resonate as a believable witness. With AI, you can ask the system to create a photorealistic image of a street scene in the nineteenth century, and it will make one with automobiles before they were invented, or it will show soldiers in previous wars taking selfies before we had cell phones. Photography cannot do that, nor should it. These are facile distortions that we have to deal with today.

Courtesy AP Photo

Palmer: How do we distinguish journalistic photographs from other kinds of imagery?

Ritchin: A journalistic photograph needs to be what one might call a “quotation from appearances,” an idea that John Berger had suggested. The frame of the image can be thought of as quotation marks, and anything within it beyond minor retouching or cropping or getting rid of some of its artifacts, such as visual noise, needs to be indicated to the reader just the way, in a verbal quotation, you would have to indicate with an ellipsis or brackets anything that has been added or subtracted from the quote itself.

If you think of the photographer as the author of the image, like a writer is the author of the text, one can quote from appearances, and when the image is no longer a quotation that has to be made transparent to the viewer either in the caption or with some other form of labeling. If one wants to make photorealistic imagery with artificial intelligence and use it in a documentary context, that has to be indicated in a prominent way. To clarify, I write, “This is a synthetic image, not a photograph,” and then I describe how the image is generated from a text prompt by an artificial intelligence system.

I was just reading in a major news outlet about an “AI-generated photo” that is meant to describe a viral meme concerning the war in Gaza, “All eyes on Rafah.” This is not a photograph, and many news outlets still confuse the two in the language they use. AI imagery has its place but cannot be allowed to be mistaken for actual photographs so that readers become skeptical of all the imagery they look at, including photographs that depict serious societal issues.

Courtesy Zila Abka/ Microsoft Image Creator

Palmer: As you have pointed out, AI is only the latest development in the decades-long evolution of digital technology. It’s neither bad nor good intrinsically, but it may, in fact, be quite destructive when used in certain ways. Where do we draw the line in journalistic photography?

Ritchin: Let’s back up for a minute. In the twentieth century, photography was largely what one might call “optical”—light going through a lens and being recorded on film. Then it became, with the invention of digital imaging, increasingly “computational”—the light going through the lens was only a starting point to be subverted, or “enhanced,” as it is often described, with an undetectable manipulation of the pixels to create something very different.

This could be accomplished either in postproduction with software or, as is now commonplace, with algorithms in the camera itself that immediately modify the image, ostensibly to please the consumer/photographer, or “prosumer.” This is particularly the case for cell phones, which are used to produce over 90 percent of the photographs made. A question arises as to whether we should still be calling this “photography” or using a more general term such as “imaging.”

Now with generative artificial intelligence neither a lens nor a camera is necessary to make a photorealistic image. The computer systems can produce one within seconds of nearly anything in response to one’s text prompts. Doing so not only makes people who never existed and events that never occurred seem as real as those that actually did, it increasingly causes people to doubt the credibility of the photographs that these synthetic images resemble. If nearly any scene can be generated in seconds and made to look like a photograph, then of what value is the photograph itself, the fact that a photographer had to be there, if one can summon up a similar or even more vivid scene from one’s living room?

The actual photograph may no longer provoke the same sense of curiosity or outrage or awe when it can be so easily simulated. Now a photograph can be more easily rejected if it does not meet a viewer’s expectations of what the world is supposed to look like, and we lose that common reference point I referred to earlier.

What can be done to restore trust in the photographic image as a witness?

Palmer: Do we understand how profoundly artificial intelligence is impacting us?

Ritchin: Generative artificial intelligence represents a paradigm shift. It may simulate photography, but there is no longer a witness present at the scene, nor is there a camera, as there is with documentary photography. But generative AI can also be quite useful when properly labeled to depict that which is outside the scope of photography—the future or the distant past, for instance.

One might show Los Angeles or Bangkok or any other city fifty years from now according to the best predictions of climate scientists should nothing be done to alleviate current trends; the result might be for governments to act proactively to minimize the predicted flooding and other kinds of destruction. This could be quite helpful, even essential, much better than waiting for the apocalypse and making extraordinary photographs of the havoc while winning major awards.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Description

Subscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Palmer: Let me frame my question with a word that we’ve discussed many times over the past several decades: democracy. You started raising the alarm about the potential for software to be used to alter what we believed were nonfiction documents forty years ago in your 1984 article “Photography’s New Bag of Tricks,” in The New York Times Magazine. Why is photojournalistic photography important to democracy, particularly now?

Ritchin: If we don’t know what is happening in the world, if we do not have common reference points, there is no way to decide how to vote, whom to vote for, even how to have an opinion on what is going on. As many have previously warned us, including Hannah Arendt, there is now a widening path leading to autocratic governments when citizens become confused enough, essentially disarmed, so that a dictator emerges who will make the decisions for them.

This is the future that we have been dangerously close to these past years, the collapse of photography and the larger media as viable reference points playing a significant part in what is happening. And we in the photographic community have done very little to safeguard the credibility of the photograph over these last decades in response to the rise of social media, the decline of trusted news sources, and the transformation into a digital environment in which the photograph, what Susan Sontag had been able to refer to some fifty years ago as a kind of “footprint,” becomes essentially malleable.

Tanya Habjouqa, Occupied Palestinian Territories, West Bank, Qalandia, 2013. After grueling traffic at the Qalandia checkpoint, a young man enjoys a cigarette in his car as traffic finally clears on the last evening of Ramadan. He is bringing home a sheep for the upcoming Eid celebration.

Courtesy Noor Images

Palmer: Are there any positive developments in the documentary realm?

Ritchin: One positive development in terms of a more democratic medium is that we are now looking at imagery from people located throughout the world who have considerably more insight into their own cultures, their own situations. Documentary photography is less frequently utilized, as the photographer and teacher Mel Rosenthal used to describe it, as a way of looking at the world through a kind of downward mobility—the middleclass, upper-middle-class photographer going to photograph poorer, marginalized people.

But much more has to be done. Why, for example, did we know so little about the people who live in Gaza before this latest conflict—who are the poets, the teachers, the athletes, the doctors, the families? Like so many others, they have been defined primarily through the lens of violence for many years. Tanya Habjouqa’s work Occupied Pleasures (2015) is a notable exception in its more uplifting perspective on Palestinian life, acknowledging a larger culture with its many pleasures without resorting to repetitive imagery of victimization and violence.

Palmer: I’m not ready to concede that generative AI has any role in nonfiction photography, but what are some of the ways you think it could be used to inform or inspire rather than deceive?

Ritchin: One of the interesting aspects of generative artificial intelligence, while it can be racist and misogynistic and idiotic, as has been widely commented upon, is that many times the images generated with text prompts go considerably beyond the stereotypes that we have in our minds. Rather than photographs that so often emulate previous photographs, the results can be surprising. There have been many instances where the image generated makes me rethink my own expectations of beauty, poverty, possibility, and so on.

When the synthetic image does not exactly replicate the photograph, but diverges from it with the wrong number of fingers, an extra piece of jewelry, an implausible twist of the body, a facial expression that I may never have seen before, it’s AI being used not to simulate a previous medium but to emerge as a new and potentially very different, provocative medium. It’s like early Pictorialist photography, which imitated certain aspects of painting before photography evolved into something quite different from painting.

Palmer: You remind me of a situation I encountered in Iraq. An editor from a major news magazine asked me if had photographed the most recent bus bombing in Baghdad when I was forty, fifty kilometers away, which was eight hours away at that time; it was a totally different reality from where I was. There was a storyline in search of the photo illustrations or the realistic photo depictions of a particular storyline, which had to do with the Global North depicting the Global South in a particular way. We still have this tradition of—whether it’s about race, it’s about class, it’s about colonialism—white folks depicting browner folks in a particular way. That’s part of the story. Transparency and the interrogation of an individual photographer’s point of view can mitigate this tendency, I think.

Ritchin: I agree completely. If I was editing a publication today, I would be presenting imagery by civilians in different situations around the world that they have contextualized for us. What did it feel like to be in Paris during the recent Olympics? Well, let me look at the cell phone imagery from seventy-five Parisians coming from very different backgrounds, not just the athletic competitions themselves photographed in mostly predictable ways. What do they have to say about what was going on beyond the media’s focus on the made-for-television facade?

We can also point to a project in Australia where refugees were detained offshore for years with no photographer or cameras present, many of them saying they were horribly abused while in captivity. A law firm, Maurice Blackburn, interviewed them for several hundred hours of testimony and then, with some who agreed to participate, made synthetic images with AI that depicted, according to the memory of those who suffered the abuse, what it looked and felt like to have been there. So here we have a paradigm shift where it’s the victims, those abused, who are able to retroactively make images that potentially can sway public opinion without a photographer needing to be present. Of course, a danger is that abusers in this or other situations could then generate synthetic imagery that makes them appear much more considerate and less abusive than they might have been.

Palmer: Let’s use as an example the iconic Kevin Carter photograph of the starving Sudanese child with the looming vulture. We can interrogate that picture because it’s a real image. It’s a real quotation from reality. We can malign, we can support, we can do all those things, but we have that reference point, and we know that it was produced with a particular methodology: human with camera interacting with the flesh-and-blood, brick-and-mortar world. This is not the result of the scraping of zeroes and ones from the metaverse. Doesn’t the former serve democracy in a way the latter cannot?

Ritchin: Yes, AI turns everything on its head because you don’t need a camera anymore, you don’t need to have traveled to Sudan. It references extant imagery that can be found online. For example, the AI images of CEOs of companies generally used to be all these white men, and AI companies have made a big attempt to change the algorithm. But now at times the results are just as distorting, where you get Nazi soldiers who are Black or, in my case, I’ve asked for an image of “white segregationists in the South after the Civil War” but what emerged was imagery depicting groups of Black men. Imagine a high school student getting similar results for a research paper.

And underlying much of this are the corporations, which are seducing us into rejecting the realities depicted in photographs, arguing that reality is just not good enough for us in a consumer society. We, the consumers, are made to feel entitled to reconfigure various realities in any way we want, rewriting histories and current events in the process. The dialectical quality of photography, its ability to show us things that were there so that we might ponder both their existence and significance, can now easily be overridden. We are encouraged to reconfigure the world “in our own image,” the title of my 1990 book on the transformation of photography in the digital age, as if we were minor deities.

Palmer: What does that then do to us as a society?

Ritchin: To some extent, we were able to share realities via photography. Now, if the photograph is so easy to simulate that we can visualize whatever we want the image to say, then why bother responding to actual photographs? They lose their weight, their credibility. Some call it “the liar’s dividend,” others call it “poisoning the well.”

And, in turn, the synthetic imagery can be easily weaponized to “show” atrocities committed by the other side, whoever that might be. One need no longer witness them; one can fabricate them. As one of my students mentioned, having pointed out fake imagery on both pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian sites, the response was largely that they already knew the truth and whether a particular image was authentic or not was not an issue.

We live in a different era now. “The camera never lies” is no longer tenable, even as a myth, which is why you and I recently helped start the campaign Writing with Light, which privileges the integrity of the photographer as the author of the image, not the fact that it was made using a camera. We must do a much better job of explaining to the public the differences among the various kinds of imagery that are being used, including how they are made and by whom. We need a widespread movement to help restore a sense of a shared reality while adding considerable nuance and complexity to our definitions of the real.

AI can also be used to add context—more context can be quite useful—perhaps suggesting other imagery on the same subject from other perspectives or linking to other resources. There’s a great deal still to think about and to further develop, but we need to act quickly, all of us, to establish parameters and best practices. Much is at stake.

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 257, “Image Worlds to Come: Photography & AI.”

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s){if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;

n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window,

document,’script’,’https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) {if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘1357435647608496’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);