The world is full of mysteries but not all of them are grand. Sure, we don’t know what the mind really is or what the inside of a black hole looks like. But there are also many mysteries hiding in the little details.

For example, we don’t know why iron inside the sun is so opaque.

Solid iron objects are everywhere around us. They’re used to make doorknobs, cooking utensils, furniture, water tanks — all sorts of things. And they’re all opaque. When light hits an iron object, it can’t pass through. Instead, some of it is absorbed and some of it is scattered. How much light an object absorbs is called its opacity: the more it absorbs, the more opaque it is.

Iron’s opacity isn’t an important detail when making a doorknob but when we’re talking about the sun, the implications are practically cosmic.

The universe’s engines

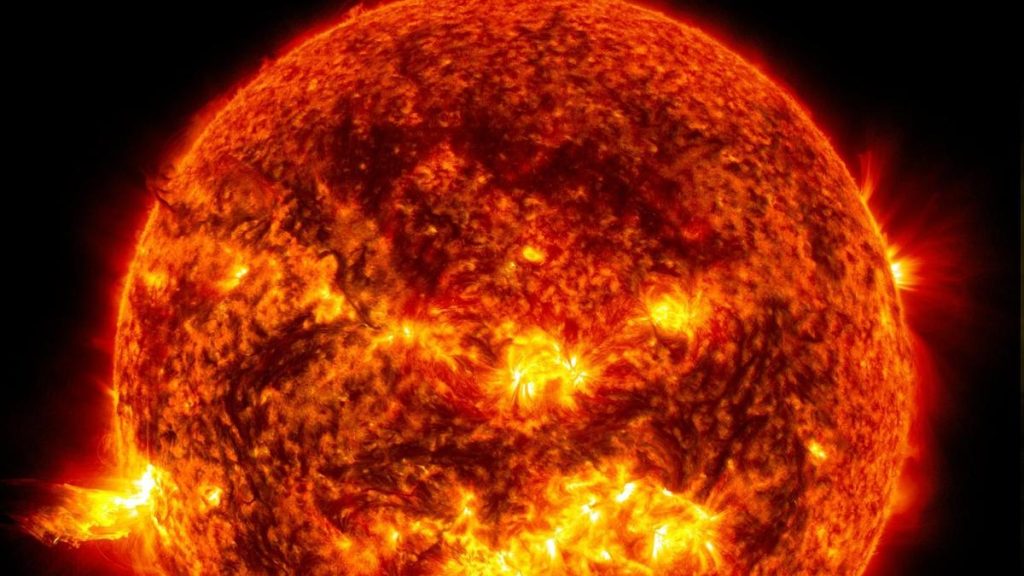

The sun is the star closest to the earth and thus the one humans have studied the most. A lot of what we know, or think we know, about different kinds of stars comes from studying the sun.

This is true on two levels. First: scientists have developed various theories to explain the sun’s properties. Over many decades, they pointed telescopes, detectors, and antennae at emissions from the star to capture electromagnetic radiation, charged particles, heat, etc. and compare the data with each theory. Then they eliminated theories that disagreed with the data and refined those that did.

On the second level, the sun is just one kind of star; the universe has many kinds. To understand their properties, scientists used the theories to build models that ‘simulate’ them. These properties include the generation of heat and energy and their movement through the star, the star’s magnetic field, its rotation and quakes on its surface, the evolution of the stellar atmosphere, the formation of sunspots and flares, and the effects of these changes on near-star space.

Stars are the universe’s engines: we can’t understand the universe if we don’t understand how stars work. When stars form, they allow planets to form around them, which they subsequently supply with light, heart, and a protective magnetic shield. (Sometimes they supply too much or too little: scientists have found more than a few exoplanets fried by their host stars or turned into giant ice balls.)

Their mass deflects asteroids and comets, and their flares energise nearby gas clouds and increase the formation of other stars. When a star dies, depending on its manner of death, it releases copious amounts of metals and other elements into the universe that aren’t made in any other natural process.

This variety of effects means stars’ properties affect the formation of star clusters, galaxies, the universe’s structure, and its evolution. Scientific models can thus simulate all these things if they get the stars’ properties right, and herein lies the rub.

Up to 400% higher

A series of independent studies until the mid-2010s reported that there appeared to be 30-50% less carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen in the sun than what models predicted.

These models aren’t easy to tweak with new data. They have been able to successfully predict some things, like the sun’s current brightness and how many neutrinos nuclear fusion in the sun’s core produces every second. The models have also become so complicated they can run only on the most powerful supercomputers. When faced with the discrepancy, modellers suspected they were due to problems in the way the elements’ abundances were measured. If the measurements are improved, the discrepancy might go away, they said.

But a notable study published in 2015 disagreed: its authors wrote that the discrepancy “could be resolved if the true mean opacity for the solar interior matter were roughly 15% higher than predicted”.

How much energy an element absorbs inside the star affects the star’s temperature profile. The authors were thus suggesting the models’ data about the opacity of elements inside the sun were off. To buttress their argument, they subjected a plasma containing iron to conditions expected at the star’s radiation/convection zone boundary, a layer about 30% of the way from the surface to its centre. They reported that depending on the frequency of radiation striking it, iron’s opacity was found to be 30-400% higher than predicted.

Dark of the shadow

Subsequent studies upheld the crux of these findings: that models were underestimating iron’s opacity. In a study published on January 27 this year, scientists reported “opacity profiles” of various elements derived from helioseismic inferences, i.e. based on the propagation of sound within the sun. They wrote: “We find that our seismic opacity is about 10% higher than theoretical values used in current solar models around 2 million degrees, but lower by 35% than some recent available theoretical values.”

But researchers who banked on models — which were based on their theories — still had to be sure if uncertainties in the measurements of the time-varying properties of the plasma in these studies could explain the discrepancy.

In a study published on March 3 in Physical Review Letters, researchers from the US and France reported they had put this question to the test and concluded the problem was indeed in the theory, not in the observed data.

At Sandia National Laboratories in the US, the team exposed a thin sample of iron to X-rays and pointed spectrometers at the X-ray source. The spectrometers observed the X-ray shadow cast by the iron sample. The team also linked up the spectrometers to ultrafast X-ray cameras that recorded changes in temperature and particle density more than one billion times per second.

The team wrote in its paper, “Our new measurements use a novel technology to measure opacity sample evolution … These measurements quantify the impact of temporal gradients on published film-integrated data and contradict the hypothesis that the temporal evolution might explain the published model-data discrepancy.”

‘Many more requirements’

The study’s challenges weren’t trivial. Measuring opacity in sun-like conditions requires technologies that didn’t exist until recently. To mimic the conditions in the sun, the electrons in a plasma need to be energised to at least 180 eV while their density exceeds 30,000 billion billion particles per millilitre. The energy came from the X-ray source at Sandia.

The thin iron sample also contained a small amount of magnesium as a tracer. The magnesium’s interaction with the X-rays, as observed at the spectrometer, allowed the team to calculate the electrons’ energy and density.

The team inferred iron’s opacity to the X-rays based on how strongly it absorbed the radiation. The more strongly it did, the darker the shadow it would cast in the spectrometer readings. This ‘darkness’ is called the line optical depth.

The paper added, “The ultimate approach to resolving the model-data discrepancy entails measuring iron opacity as a function of time. However, that must satisfy many more requirements, including absolute transmission measurements, rather than line optical depth reported here, and formal uncertainty determination, while measuring plasma conditions.”

“Such an absolute opacity approach is presently under investigation,” the team added.

Published – March 20, 2025 05:30 am IST