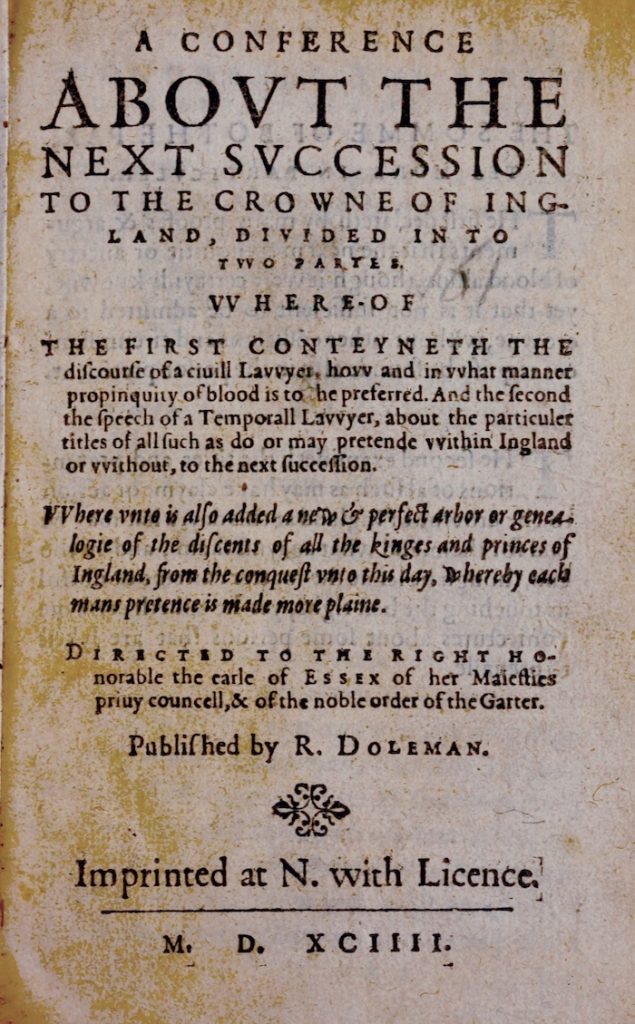

In December 1593 Robert Persons, a leader of the English Jesuits on the Continent, was putting the finishing touches to a book he had been working on. Written in the English seminary that he had recently founded with the support of the Spanish king Philip II at Valladolid, A Conference About the Next Succession to the Crowne of Ingland describes a fictional meeting of concerned Englishmen who are determined to resolve the long-running question of who should succeed Elizabeth I. Persons’ meeting takes place in Amsterdam and features a gathering of gentlemen of various professions from across the confessional divide. Two unnamed lawyers, one an expert in civil law and the other common law, make the case for the viability of various potential claimants, who include James VI of Scotland, his cousin Arbella Stuart, Edward and Thomas Seymour (the sons of Katherine Grey), Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, and the Infanta of Spain, Isabella Clara Eugenia. While the conference was imaginary, the issues Persons’ characters debate were not. Anxiety over the succession had been an almost constant issue in English politics from the time of Elizabeth’s ascension in 1558, but as the century approached its end the need to resolve the matter became ever more vital – especially to those who held the chance to succeed the ageing queen.

While the English crown had traditionally been passed down through the hereditary principle of primogeniture, there was no fixed rule to govern the succession. When the 25-year-old Elizabeth became queen it was assumed that she would marry and have children to extend the Tudor line. As time passed, and her numerous courtships all ended in failure, many within her Privy Council and Parliament argued that Elizabeth should name her own successor through the use of Parliamentary statute, just as her father had done in his trio of succession Acts. Elizabeth refused. While her sister Mary ruled, Elizabeth had become a lightning rod for any conspiracy or discontent against the regime. She saw how a known heir could become the focus of opposition, and for that reason she determined to hold closely the succession as a matter of royal prerogative.

Though Elizabeth attempted to stop discussion of the succession, particularly when the topic arose in Parliament, she could not halt it completely. Her wishes did not stop people from writing about the matter, either. Between 1562 and 1571 six succession tracts were written: John Hales’ A Discovrs uppon certen pointes towchinge the Enheritounce of the Crowne (1563), the anonymous Allegations against the svrmisid title of the Qvine of Scotts (1565), the also anonymous Allegations in behalf of the high & mighty princess the Lady Marie, now Queen of Scots (1566), an anonymous ‘Letter’ (1566), Roger Edwardes’ Castra Regia (1569), and John Leslie’s A defence of the honour of the right highe, mightye and noble Princesse Marie Quene of Scotlande (1569). While the conclusions of these tracts were directed by the confessional leanings of their authors, they were primarily focused on debating the laws and customs which could impact the succession. They argued about the application of common law to the royal succession, wrangled over the validity of Henry VIII’s will, and quibbled as to whether Scotland could be considered foreign since it was not located across any sea. With no answer in sight, the written debate was brought to an abrupt end in 1571 when a new Treasons Act was passed which outlawed ‘any Book or Work printed or written’ that declared ‘that any one particular person whosoever it be, is or ought to be the right Heir & Successor to the Queen’s Majesty’. This Act led to a halt in the production of succession tracts for over 20 years, but it could not hold back the tide forever.

Uncommon Law

The potential claimants to Elizabeth’s throne were distant relatives. For most, the obvious choice lay with the Scottish House of Stuart, which descended from Henry VIII’s eldest sister Margaret. The Scottish claim was debated extensively as, while it was the strongest by primogeniture, there was a common law rule that foreign-born people could not inherit in England – though there was doubt as to whether this applied to royal succession. There was a further issue as Henry’s will had clearly removed Margaret’s descendants from the succession, but its validity was often challenged as it had not been signed by the king himself. Regardless of these questions, few were prepared to deny the Scottish claim completely. After the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, in February 1587, her only son, James VI of Scotland, assumed her claim. James had grown up as a king; he later referred to himself as a cradle king, having been crowned at only 13 months old. As a married Protestant monarch with a son to guarantee the continuation of his line, James appeared a sound candidate for the English throne. He was convinced that there was no better candidate. However, as long as Elizabeth refused to name James as her heir, the question of succession persisted, and it provided an opening for Persons to meddle.

Persons’ book was from the outset a political ploy. Following its completion, two thousand copies of A Conference were printed by Arnout Conincx in Antwerp in 1594. Despite the reservations of the Jesuit General, Claudius Aquaviva – who thought the book likely to harm other Jesuit endeavours once its authorship was uncovered – the decision was taken for it to be distributed. By the following year A Conference had been smuggled into England and began to circulate. It soon found its way into the hands of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, who had his son Robert send a copy north to James. After reading A Conference James’ confidence in succeeding Elizabeth was shaken, as, much like earlier succession tracts, Persons’ account was at first glance focused on the law – but its mangled reading of that law culminated in the suggestion of a different successor.

Persons’ tract built not only upon the earlier legal debates over the succession but also upon more recent developments. In 1584, when English fears that Elizabeth would be assassinated were at their peak following the murder of the Dutch Protestant leader William of Orange, the Bond of Association was created. Francis Walsingham and William Cecil, the two privy councillors behind the Bond, sought to unite the nation in a public expression of loyalty to their queen. The Bond was highly unorthodox for the English political classes, and resulted in public ceremonies of oathtaking around the realm. However, it had a more sinister aspect, as part of the oath bound those who swore it to ‘never desist from all manner of forcible pursuit against such persons, to the utter extermination’ of those found guilty of plotting Elizabeth’s death, and to prevent the conspirators’ heirs from succeeding the throne. The Bond was essentially a lynch law. Its anomalous nature was significantly altered by the 1585 Act for the Queen’s Safety which safeguarded any heirs from repercussions and restrained its excesses. Though the Bond and the Act were fundamentally different documents, in the hands of Persons they became entwined. As Persons bluntly put it, since:

the lady Mary late Queene of Scotl[an]d, mother of the king, was condemned and executed by the authority of the said parliament, it seemeth euident, vnto these men, that this king vvho pretendeth al his right to the crowne of Ingland by his said mother, can haue none at al.

With that in mind, Persons claimed that the rightful successor could only be the Catholic infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain, who traced her claim back through John of Gaunt to Edward III, and who, happily, was the eldest daughter of Persons’ patron, Philip.

‘The lawfull successor’

While Persons’ tract was based on a distortion of English law, it worried James. John Carey, the marshal of Berwick, reported to William Cecil that James had received a copy of the tract and was ‘much discontented’. Some form of action needed to be taken to counteract it; James decided that the best way to deal with Persons and his Conference would be to fight words with words and engage writers of his own. Thus began a public relations mission to argue and publicise his right to the English throne. While printing and writing on the succession had been outlawed by the Treasons Act in England, it did not stop the production of succession tracts outside England’s borders. Using Persons’ example, James wrote, commissioned, or ordered printed five separate tracts to argue for his claim to succeed Elizabeth, and used the printers in Edinburgh to spread his message far and wide.

One of the first of these tracts was written by Alexander Dickson. Dickson (or Dicsone) was a Scot who received his education at the University of St Andrews. He then lived in London for a time and was a known supporter of Mary Stuart during her imprisonment. He later returned to Scotland and by February 1598 it was widely known that he was writing a tract on the succession, with James’ support, to counter Persons’ ‘pretended conference at Amsterdam’. In Dickson’s Of the Right of the Crowne, after considering the web of law, statute, and primogeniture, he concluded that James’ claim to the English throne was just. The English ambassador at the time, George Nicolson, suspected that Dickson’s tract would be sent out of Scotland to be printed, but it never was. It has been speculated that James himself prevented the work from being printed. Dickson’s work was highly critical of Elizabeth’s decision not to settle the succession, and argued that she had endangered her kingdom by encouraging James’ enemies. The book was not likely to promote much understanding or goodwill from the woman James hoped to succeed.

While Dickson’s potentially embarrassing work was shelved, James sought another tract to distribute in its place. Shortly after Persons’ A Conference was published Peter Wentworth, a wayward English Parliamentarian, wrote a response. Wentworth had written two previous succession tracts and had been involved in numerous unsuccessful Parliamentary attempts to have Elizabeth establish the succession. Imprisoned in the Tower after yet another attempt to force the issue, he wrote A Treatise Containing M. Wentworth’s Ivdgement Concerning the Person of the True and Lawfull Successor to the Realmes of England and Ireland. In his final mediation on the issue Wentworth considered James to hold the best right to the English throne based on blood descent. He argued that, since James’ right flowed through both his mother and his father, it did not matter even if Persons was right about the Act for the Queen’s Safety regarding Mary. Indeed, the Act ‘cannot defeate or hinder the Scottishe King of that right which commeth in to him by his father, and which hath the firste and next place, if his mothers title should abate’. He then concluded, in a rather surprising manner considering his outspoken career devoted to Parliamentary rights, that ‘Parliament cannot defeat the lawful successor’.

The printing of books like Wentworth’s was treasonous in England, but after Wentworth’s death in 1596 it was smuggled northwards by an unidentified Englishman and found its way to James. To have the support of such a well-known agitator from the House of Commons – a Puritan who repeatedly pushed the rules of free speech to advocate for the establishment of the succession – was a boost to James’ cause. It showed that it was not only Scotsmen who supported his claim, but also Englishmen with a thorough understanding of their own laws. In 1598 James ensured it was published.

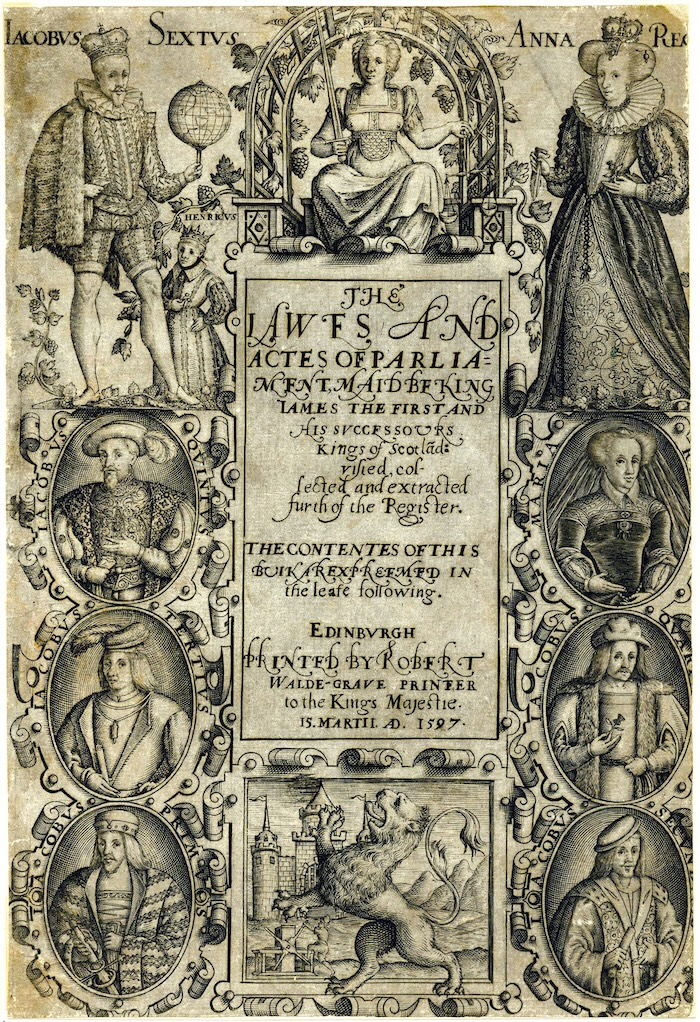

After being smuggled from the Tower of London, Wentworth’s work was printed by James’ royal printer in Edinburgh, the exiled Englishman Robert Waldegrave. Waldegrave had been a printer in London but had fled England after his involvement in producing the Presbyterian anti-episcopal Marprelate tracts – a set of radical works which attacked the governance of the English Church by bishops – was uncovered. James appointed him as royal printer in 1590. For Waldegrave himself the situation was fraught. He was fully aware that involvement in the succession question, and the printing of such texts, would most likely prevent him from being able to petition for his eventual return to England. As the royal printer, however, he had little choice and in the final years of the 16th century three succession tracts would emerge from his workshop, the first of which was by Wentworth.

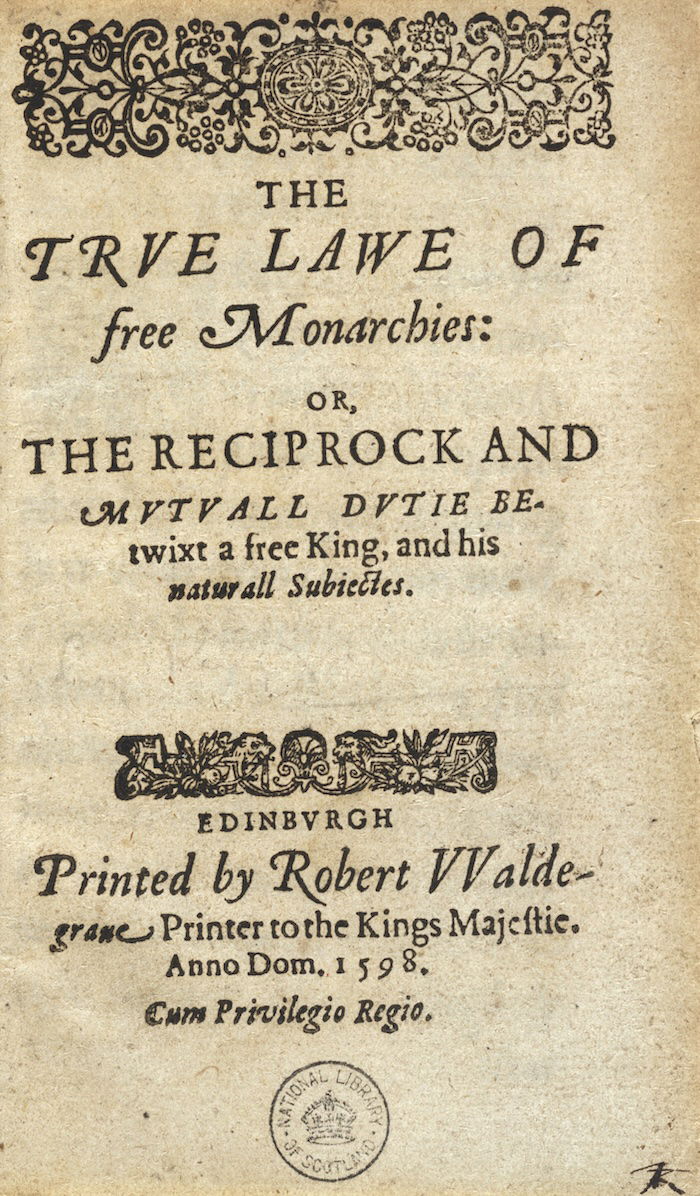

James’ strategy was not limited to publishing the works of others. In 1598 he outlined his own thoughts on kingship and monarchy in The True Lawe of Free Monarchies. James was a highly educated monarch who had received a rigorous humanist education at Stirling Castle. He carried a love of writing throughout his life and it is no surprise that when the time came to argue for his right to succeed Elizabeth he could think of no better author than himself. Among his arguments in The True Lawe was the crucial point that he held the right of succession by primogeniture to overrule any human law, especially since in his view the ‘King is aboue the lawe, as both the author and giuer of strength’. In his own mind the blood which flowed through his veins connected him directly to the throne; it could not be interrupted by an idiosyncratic web of law and tradition. With his thoughts on the matter firmly spelled out, he turned to Waldegrave to have it printed.

The following year, 1599, saw the publication of another succession tract in Edinburgh. The work had a typically forthright title: A treatise declaring, and confirming against all obiections the just title and right of the moste excellent and worthie prince, Iames the sixt, King of Scotland, to the succession of the croun of England, and is somewhat mysterious in its origins. The work was written under the pseudonym ‘Irenicus Philodikaios’ and while he claims to be an Englishman in the text, there is no evidence of his true identity. ‘Philodikaios’ sought to present himself as a loyal and loving subject, as he argued for the primacy of succession by primogeniture. He concluded that ‘the right of the croune by descent of blood falleth vppon JAMES the sixt, King of Scotland’, a right that was strengthened as it was traced through ‘his fathers side, as of his mothers’. With James as the clear successor, and the tract written for the benefit of Philodikaios’ ‘deare countrie-men’, this work was ideal for James’ purposes. It too was given to the royal printer.

The last word

In 1600 the fifth and final succession tract with connections to Scotland was published. The work was written by John Colville, a minister educated at the University of St Andrews, who had left Scotland for Europe three years earlier, following his involvement with the politically volatile Francis Stewart, earl of Bothwell, and never returned. His tract The palinod of Iohn Coluill was itself a retraction of a previous work in which he had not only denied James’ right to the English throne but had also claimed that he was illegitimate. In his palinod, Colville completely turned his back on his previous stance. He argued that the hereditary principle was what primarily guided the succession to a crown, and that by right of primogeniture James should succeed to the English throne. In his conclusion Colville addressed the English, urging that ‘reason and good conscience doth recomend unto them the King of Scotland, because he is the righteous successor’. Colville sent a copy of his palinod to James who happily received it. With the palinod in his hands James had another work to add to his growing body of public materials supporting his claim, and he handed it to Robert Charteris, another printer with royal ties, to have it published.

In the final years of Elizabeth’s reign it became ever clearer that James would succeed her. His efforts in writing, commissioning, and printing tracts formed a consistent strategy to publicise his right to succeed by primogeniture and to counter any claims such as those put forward by Persons in his tract. It is almost impossible to measure the full impact of James’ strategy or of Persons’ work, which started this flurry of publishing. In England discussion of the succession and publication of works was still against the law – indeed anyone who ‘willfully set upp in open place publishe or spreade any Bookes or Scrowles to that effect, or shall print bynde or put to sale’ was guilty of treason. However, from the State Papers of the English government it is clear that they were aware not only of Persons’ book, but also James’ attempts to counter it with works of his own. Elizabeth herself, ever the mistress of her own realm, was also likely aware of debates which had surrounded the succession as the sun slowly set on her reign.

Most of the works published as part of James’ strategy faded into the background once he became king of England, their purpose served, but the same cannot be said for Persons’ A Conference. The book initially created a divide among exiled English Catholics, some of whom felt it was too strongly in favour of a Spanish claimant to the throne. The work then had a rather strange afterlife, later resurrected by political opponents of Charles I and James II for its consideration of elective monarchy. Succession tracts continued to be a feature of English politics and, as each monarch’s reign drew to a close, or finished with death – as James’ did in March 1625 – works concerning the succession were again written and disseminated. But at no point were printed tracts as pivotal in settling a succession as they were in the final years of Elizabeth’s reign: it was James’ war of words which ensured his claim was widely known when he travelled south to become king of England in 1603.

Elizabeth Tunstall is a visiting research fellow at the University of Adelaide and the author of The Succession Debate and Contested Authority in Elizabethan England, 1558-1603 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2024).