In the United States, photography has long struggled for the respect afforded to the more established mediums of painting and sculpture. From the 1930s onward, a prevailing consensus held that photography would only be seen as painting’s equal if its practitioners took advantage of the inherent qualities of the medium—what set it apart from other art forms—namely, its sharp focus and ability to render minute detail. Ansel Adams and his friends in Group f/64 deemed the popular style of Pictorialism, with its soft-focus attempts at mimicking the effects of painting, to be hackneyed and gimmicky and warned that photographic imitations of paintings would always be considered second-class.

There were notable exceptions, of course. Man Ray, for example, saw photography as one of many tools he might deploy to realize his creative vision and often made composite artworks. László Moholy-Nagy, coming from the radical Bauhaus in Germany, brought a similarly catholic approach to the Chicago Institute of Design, where he taught Harry Callahan. Kunié Sugiura’s practice, which melds photography and painting, emerged, in part, from this heritage. A student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) from 1963 to 1967, Sugiura studied under Kenneth Josephson and Frank Barsotti, who had been students of Callahan. But while her work bears hallmarks of Moholy-Nagy’s legacy, Sugiura’s approach to photography also reflects her fierce independence of mind and the influence of Japanese aesthetics.

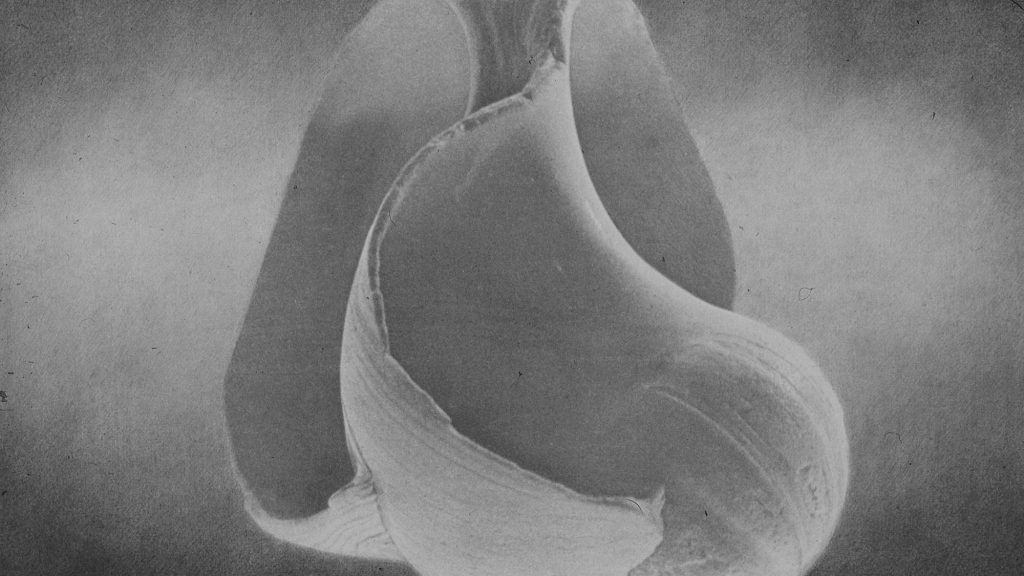

Kunié Sugiura, Sea Shell 2, 1969. Photographic emulsion and graphite on canvas

When Sugiura first began creating pieces in the late 1960s that combined photography and painting, their hybridity made them difficult to categorize, effectively precluding her from market success at a time when US galleries, collectors, and photography-focused curators were less receptive to work that blurred the lines between mediums. From today’s perspective, however, her early defiance of traditional boundaries demonstrates her prescience as an artist. Her oeuvre is perhaps best understood in relation to the explosion of photography into the realm of contemporary painting in the 1960s that started with artists such as Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, who were early influences.

Sugiura moved to New York in 1967, mere days after graduating from the SAIC. Without access to a color darkroom, she was forced to pivot and find a new mode of producing photographs. Eventually, she began printing on canvas that she coated by hand with photo-emulsion, using a substance evocatively called Liquid Light. This was a radical departure from her previous efforts as it was a black-and-white process that required far less precision and fewer hours in the darkroom to get satisfying results. Sugiura rejected mainstream photographic trends in favor of trying something unique and unexpected.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Description

Subscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Mounting a 45-degree mirror to her enlarger, Sugiura projected her negatives onto treated canvas hung on the wall of her darkroom, washing the results in her bathroom. By using hand-coated canvases, she could create works of a scale nearly impossible at the time with commercially available photographic paper. Her first experiments were on the smaller side, but she eventually made examples that were as large as approximately six by eight feet. “I was really interested in Andy Warhol’s canvases,” she has stated. “So, I started making things I had taken nearby [the studio] and enlarged them. Then, I gradually made them bigger.”

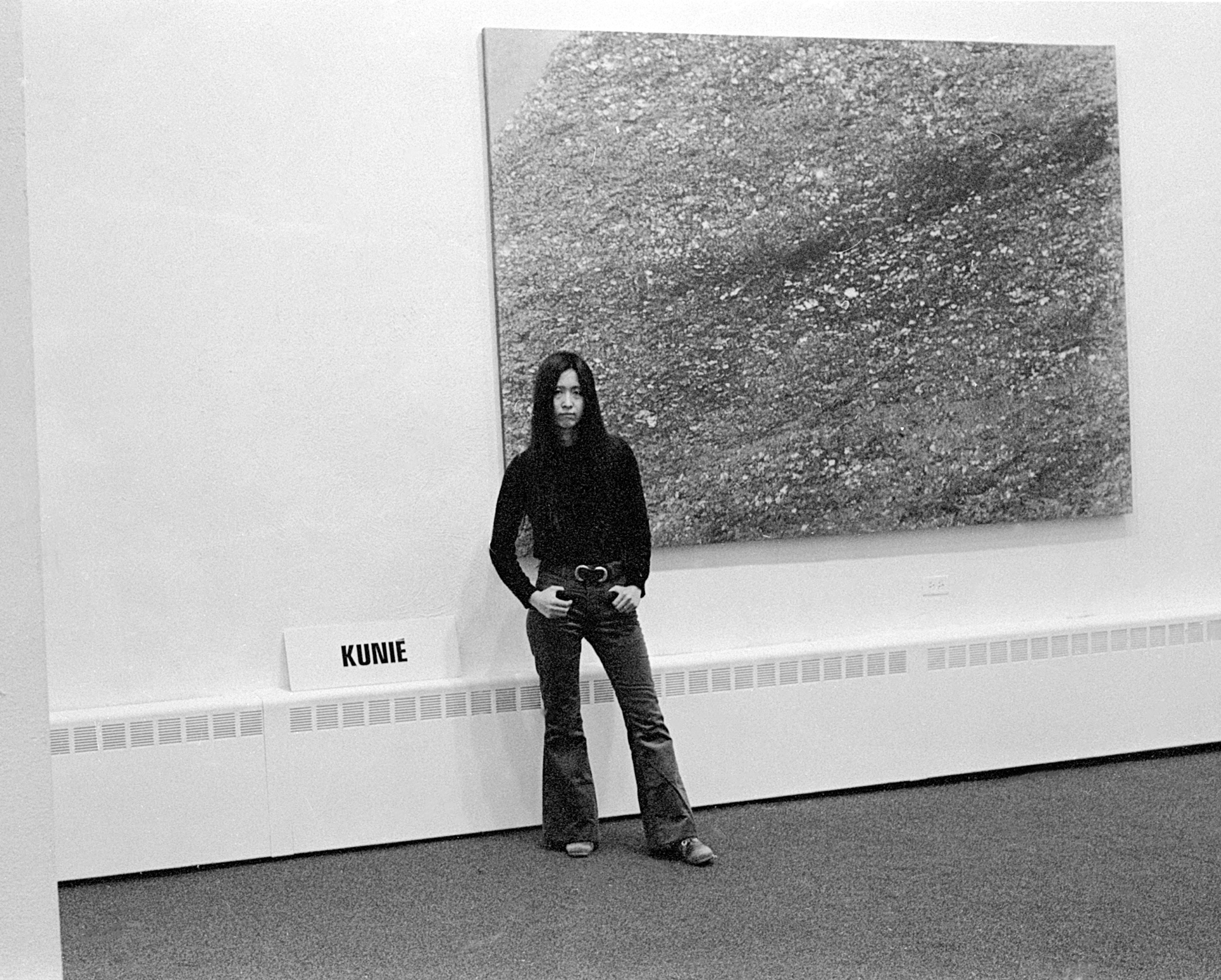

It was a strenuously physical and messy business to wrangle thick sheets of wet fabric of such enormous dimensions by herself in the darkroom. She often wore a bathing suit while printing to avoid soaking her clothes. A portrait of the artist posing in front of her work in a 1972 exhibition gives a sense of the scale of one of these oversized pieces in proportion to her body.

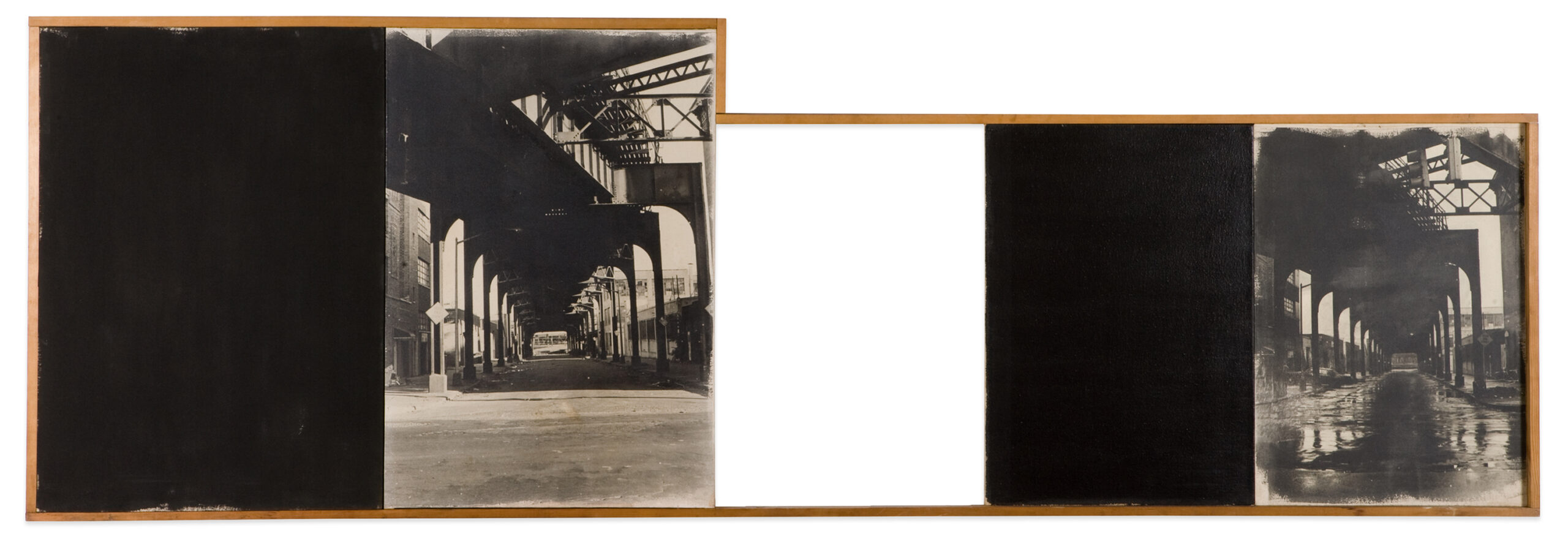

Kunié Sugiura, Christie Street, 1976. Photographic emulsion and acrylic on canvas

Kunié Sugiura, Sidewalk Palms, 1980. Photographic emulsion and acrylic on canvas, wood

The subjects of the largest in the Photocanvas (1968–72) series are mostly natural details: close-ups of sand, pebbles, an ivy-covered wall, the pattern of bark on a tree. Some are so closely cropped as to become almost abstract. As one reviewer wrote in 1972 of the experience of viewing these blown-up details, “The extreme change of scale is a visual shock. Thrown out of focus by the enlargement and simultaneously deprived of recognizability, the final image seems almost topographical.”

Even before she took up a brush, Sugiura was gesturing toward painting. At first glance, one might not recognize these works as photographs, especially because the artist enhanced many of the compositions with graphite and daubs of acrylic paint to accentuate certain details or increase the contrast, which was lost in the enlargement process. Printed on a rough canvas surface, they have a dreamlike quality and often dissolve at the edges, evoking a faded memory. In their drowsy softness, they are reminiscent of the Pictorialist compositions Ansel Adams and his “straight photography” contingent railed against. They are impressionistic, offering more feeling than detail.

Even before she took up a brush, Sugiura was gesturing toward painting.

Eventually, Sugiura would do more than just reference painting; she merged painted and photographic elements together into hybrid objects. It did not happen immediately, however. For a time in the early 1970s, she abandoned photography altogether. As Sugiura later recalled, “There was a period when I only did painting. But it turns out that painting is incredibly difficult. I struggled with it. That lasted for two or three years.” Serendipitously, she one day showed a friend some of her photographs printed on canvas next to paintings in the studio, and he remarked that they looked interesting together. Thus began her experiments with conjoining the two. The timing was fortuitous, as she was feeling stymied in her practice and in need of a breakthrough.

Kunié Sugiura, Oneway, 1979. Photographic emulsion and acrylic on canvas, wood

Kunié Sugiura, Promontory, 1980. Photographic emulsion and acrylic on canvas, wood

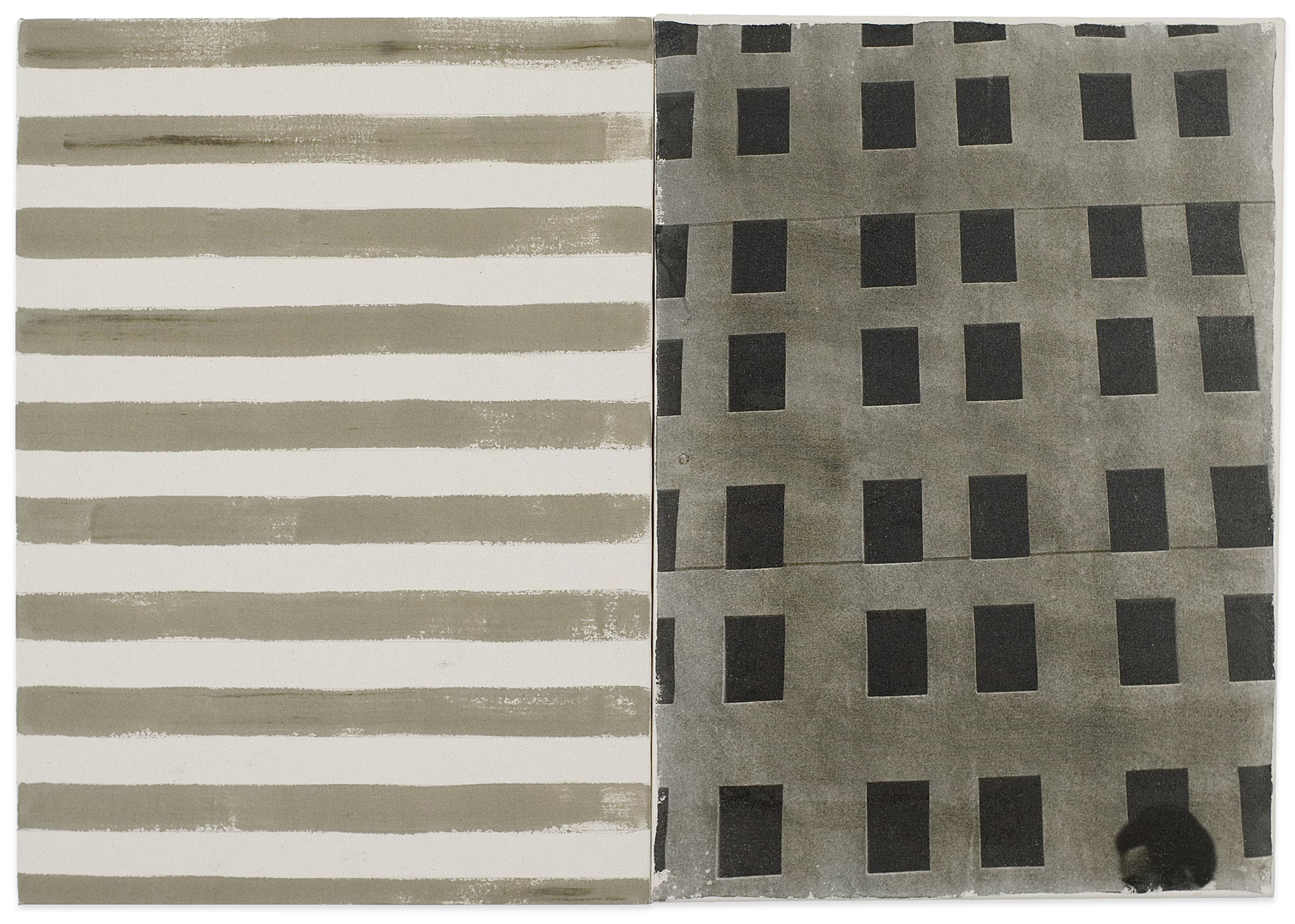

The Photopainting (1975–81) series was influenced by the work of Warhol and Rauschenberg, who also printed photographs on canvas, but Sugiura was doing something markedly different. Warhol and Rauschenberg generally screen-printed images culled from the media, often of famous people or momentous current events. Sugiura, by contrast, took her own photographs and printed them on canvas in the darkroom, cropping, enlarging, or pairing details with painted components. In time, she also incorporated wooden elements, which frame the canvas parts and connect them to one another, giving the pieces a sculptural quality. Where Warhol and Rauschenberg were referring to popular culture and history, Sugiura was responding to the natural and urban worlds around her.

While the subjects of the Photocanvas series are generally organic forms, many of the examples in the Photopainting series depict urban scenes, both in New York and in places she visited, notably Los Angeles. The painted portions of these composite pieces are simply executed, but the choice of their size and color in relation to the photographic elements is nuanced and visually sophisticated, resulting in unexpected and dynamic pairings. Sugiura does not shy away from beauty, but she also often revels in the grimy glory of New York, which has a visual appeal of its own, especially when lit up at night.

In the Photopainting series, Sugiura often deploys empty space to profound effect, as in her monumental Deadend Street (1978). The two photographs that comprise the work were made at the same location near the South Street Seaport in New York on different days: the one on the right after rain and the one on the left on a dry day. The surfaces of the painted panels directly correlate with the content of the photographs, the glossy surface on the right-hand panel evoking the rain-soaked pavement and the matte texture on the left suggesting dryness. The void at the center of the piece serves as a break, or a breath, connecting the two sides, a gap inspired by the Japanese concept of ma, which, in its simplest translation, refers to a pause in space and time.

Kunié Sugiura, Deadend Street, 1978. Photographic emulsion and acrylic on canvas, wood

All works courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Opposite: courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Sugiura was hospitalized in 1990 with a collapsed lung and had numerous X-rays taken during the recovery process. At that time, X-rays were made on heavy-duty film, and Sugiura was excited by their mysterious beauty and the way they rendered the human body fragmented and foreign. She took her X-rays home and printed from them in her darkroom, later persuading her doctor to give her the discarded films of other patients and eventually accumulating a large collection. Over several years, Sugiura made various types of playful compositions using these found negatives. More than twenty years later, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Sugiura revisited her X-ray negatives, combining them with painted canvases. Vertebra (2021), featured on the cover of Aperture’s Spring issue, is Sugiura’s first large-scale grid, a piece that can be configured in various ways. Here, the images of spinal columns become totemic, their repetition rhythmic.

From the time she first began printing on canvas in the late 1960s, Sugiura has willfully breached boundaries between mediums, making genre-defying artworks that, as she has said, “break with conventions and traditions of both painting and photography.” And yet, despite the inherent rebelliousness of the act, the gesture does not overwhelm the vision. Rather, Sugiura fluidly and gracefully combines techniques to make dynamic and original hybrid forms where the whole is more than the sum of its parts.

This essay is adapted from the monograph Kunié Sugiura, forthcoming from MACK. An accompanying exhibition, Kunié Sugiura: Photopainting, will be on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, from April 26–September 14 2025.

See more in Aperture No. 258, “Photography & Painting.”