Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

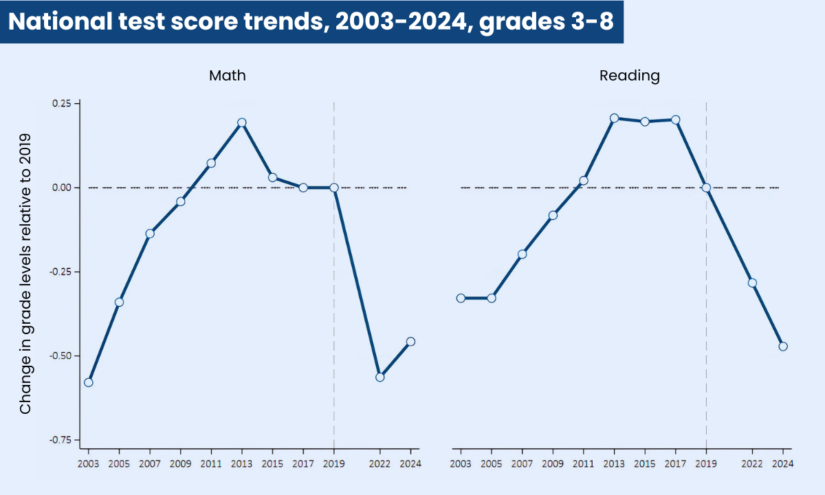

More than five years after the first appearance of COVID-19 on American shores, 94 percent of elementary and middle schoolers live in districts that still have not returned to pre-pandemic levels in math and reading, according to a new report from a group of internationally recognized education experts. The authors find that the average pupil is still half a year behind in each core subject compared with children in 2019.

Released Tuesday morning, the analysis is the latest dispatch from the Education Recovery Scorecard, a data project led by a team of researchers at Dartmouth, Harvard, Stanford, and the testing group NWEA. In two studies released last year, the consortium unearthed evidence of lagging academic growth in high-poverty areas since 2020, along with slight gains resulting from billions of dollars in federal assistance to K–12 schools.

This week’s update comes on the heels of a disheartening publication of test scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, often referred to as the Nation’s Report Card. While some had hoped that results from that exam would provide reason for hope, only minimal progress was made in fourth-grade math; reading scores were actually worse than in 2022, the nadir of the pandemic.

Thomas Kane, a professor of economics and education at Harvard, compared the sustained learning loss of the last few years with “the tsunami following the earthquake” — a destructive after-effect that has almost entirely resisted remediation efforts by local, state, and federal authorities. Struggling students, in particular, have fallen further behind their higher-performing peers, he observed.

“Given all the money that’s been spent, and the fact that students already lost ground between 2019 and 2022, you would have expected that there would be some bounce-back in reading,” Kane said. “But no, actually. Students continued to lose ground, especially at the bottom end.”

While NAEP offers state-by-state comparisons, along with the results from several dozen major urban districts, the Scorecard group combines those figures with local testing data for 35 million students across 43 states, allowing the public to chart the trajectories of individual districts since 2019.

Given all the money that’s been spent, you would have expected that there would be some bounce-back in reading.

Thomas Kane, Harvard University

Across the country, Kane and his collaborators calculate, just 11 percent of students in grades 3–8 are currently enrolled in districts where average reading levels exceed those measured in 2019; 17 percent are in districts where math knowledge is higher than the last pre-pandemic year. Set against the continuing fall in literacy, a slight rebound in math scores — about one-tenth of one grade level since 2022 — represents most of the good news.

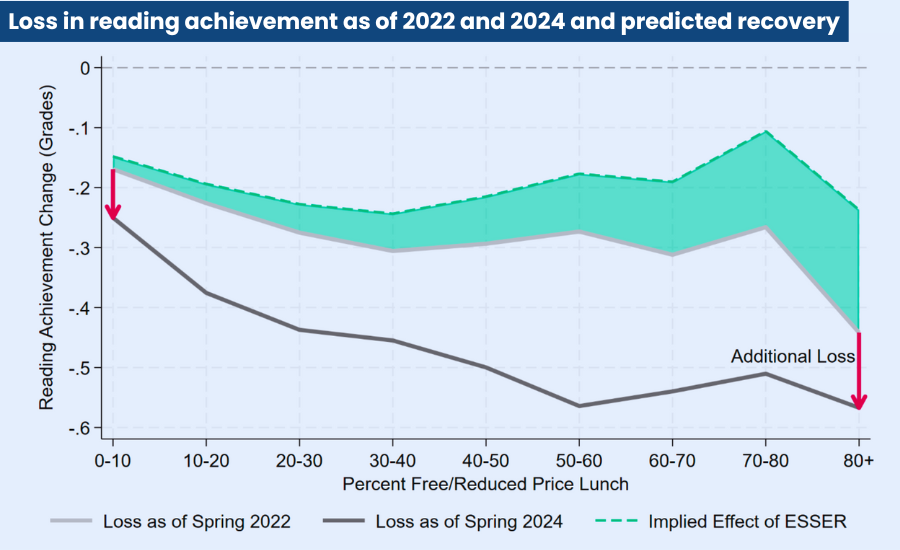

In relatively poorer communities, that silver lining is almost entirely accounted for by federal ESSER funds, which totaled $190 billion between 2021 and 2024. The report indicates that those grants prevented an even greater freefall in learning, while noting that “there were higher-impact ways to use the dollars” to speed student recovery.

Rebecca Sibilia is the founder of EdFund, a research and advocacy group that advocates for more and better-designed resources for schools. A frequent critic of the quality of school finance data, she said the breakneck pace at which ESSER dollars were appropriated and distributed made it virtually impossible for them to be maximally effective.

“We absolutely have research that shows money matters, and helps us understand how money matters,” she said. “ESSER was not constructed in a way that aligns with that research.”

Michael Petrilli, president of the right-leaning Thomas B. Fordham Institute, called the Scorecard study “devastating.

“We already knew that the bottom had fallen out for most states, but now we see how hard it is to find districts bucking the terrible trends,” he wrote in an email.

‘Two kinds of bad news’

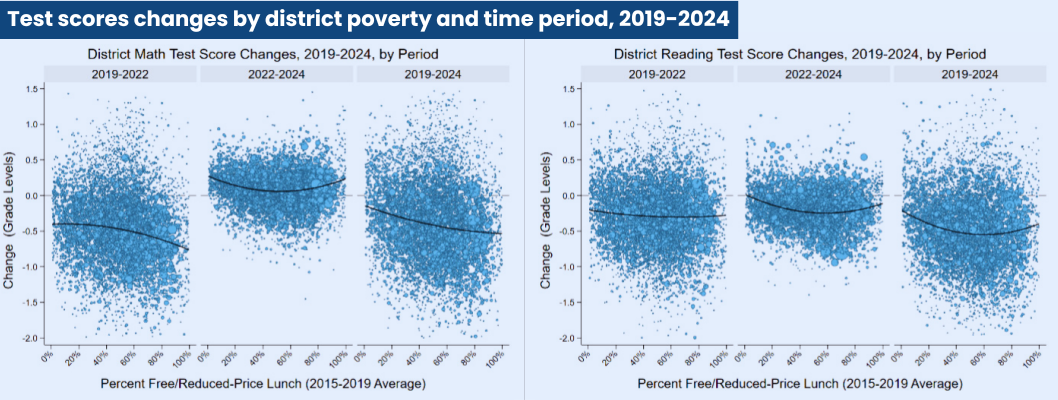

Perhaps the most alarming trend of the period bridging the COVID depths of 2022 and the present day has been a substantial rise in educational inequality.

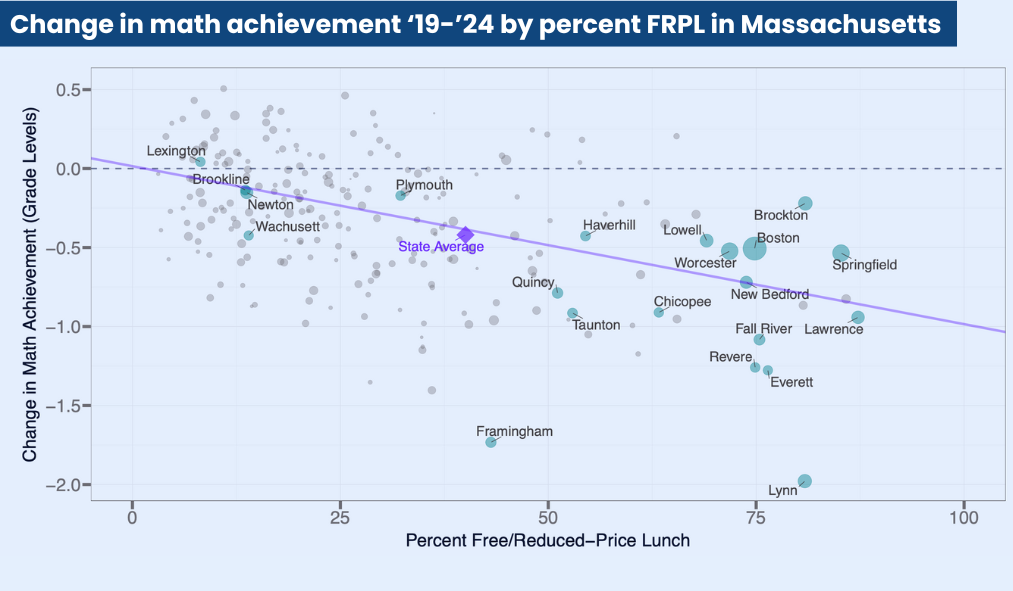

By sorting thousands of school districts according to their number of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (a commonly used proxy for poverty), the Scorecard researchers found that academic recovery over the last two years has proceeded much more quickly in affluent areas.

In nearly one-third of all low-poverty school districts, math performance has been restored to the pre-pandemic status quo; the same is true in just 8 percent of high-poverty districts. In all, over 14 percent of the richest districts (i.e., those where household income is higher than in 90 percent of other places) have returned to 2019-era learning in both math and reading, compared with less than 4 percent of the poorest districts.

A similar dynamic has been apparent in NAEP scores going back more than a decade. While the 2010s saw gradually declining results on average, the highest-scoring students tended to make some progress in each administration of the exam. Meanwhile, their struggling classmates experienced much larger reversals. Since 2013, the disparity in fourth-grade reading performance between kids at the 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively, grew by 14 points; the divergence in eighth-grade math grew by 16 points over that decade.

Stanford sociologist Sean Reardon, who leads the Scorecard project alongside Kane, said the widening gaps make it clear that the task of general academic recovery must be accompanied by a special focus on students who are at risk of never getting back on track.

“There’s two kinds of bad news between the NAEP results and ours,” Reardon said. “One is the disappointing lack of recovery, and even continued decline, in reading. Those average trends are disappointing, but they’re compounded by the fact that the negative trends are worse for the kids in the highest-poverty districts.”

The worrying class bifurcation is apparent from coast to coast, but Kane specifically identified achievement gaps in his home state of Massachusetts. There, the well-to-do Boston suburbs of Lexington and Newton have either surpassed their academic performance of a half-decade ago or have very nearly dug themselves out of the hole.

Just a few miles away, however, in the working-class cities of Everett and Revere, the average student is floundering more than a year behind the pace set by similarly aged students just five years ago. In Lynn, one of the most troubled school districts in the state, elementary and middle schoolers are two years behind in math and over 1.5 years behind in reading.

The report includes case studies from relatively disadvantaged communities (including Union City, New Jersey, Montgomery, Alabama, and Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana) that had made significant strides back to normalcy. But the typical such district still faces years of work to regain what was lost.

Joshua Goodman, an economist at Boston University, said that education leaders needed to guard against the sense that emerging gaps simply represented the “new normal.” If he’d been told in 2020 that children would still be scuffling to this extent by the middle of the decade, he said, he would have been shocked and disappointed.

“I think I implicitly believed that, once the pandemic receded and schools reopened, the normal operation of kids’ lives would somehow cause them to bounce back,” Goodman recalled. “I don’t know if I was just being naive or not thinking it through properly, but this is a very grim result.”

Meager return from COVID funds

The dour note struck by observers is largely related to the meager returns of Washington’s relief efforts.

Previous work from the Education Recovery Scorecard has pointed to a modest bump in student performance that followed an infusion of billions of dollars to states and districts. But that upward movement didn’t come close to reversing the full extent of COVID’s damage; for that, researchers estimated, hundreds of billions of dollars more would be needed.

With federal funds now expired, and no new federal appropriations on the horizon, ESSER’s final impact can begin to be measured. For every $1,000 spent per student between 2022 and 2024, the authors estimate, math scores increased by roughly .005 standard deviations (a scientific measure showing the distance from the statistical mean).

In comparison with other policy changes in education, Kane and Reardon showed, this is a fairly small figure — just a tiny fraction of the gains enjoyed by schools that adopted the Success for All reform model, for example, or those that followed the implementation of high-dosage tutoring programs.

Kane said the relatively freewheeling structure of ESSER funds — states were only required to spend 20 percent of the aid on programs specifically aimed at lifting student achievement — meant that many expenditures were not efficiently targeted at the schools and students of greatest need. The small payoff could serve as a warning to Republicans reportedly considering dismantling the Department of Education and disbursing its various revenue streams to states to spend freely.

“This is an example of bypassing federal regulators, or even bypassing state regulators, and giving all the money directly to school districts,” Kane argued. “We just saw what happens: Some school districts will figure out how to use the money well, but others won’t.”

Referencing widely circulated papers by school finance researchers Kirabo Jackson and Eric Hanushek, Sibilia said the general case for spending more on K–12 schools was sound. But ESSER money was sent out the door quickly, often to districts that didn’t serve large numbers of needy students. While spending it, district leaders had to make fast decisions with incomplete information.

The simultaneous and temporary explosion in districts’ budgets had led to a concurrent increase in shoddy vendors for services like tutoring and professional development. No matter the amount of money that Congress might have awarded, she added, the effects of ESSER would have been dampened by the limited supply of high-quality providers.

“There are a few researchers in the country that are dogmatic in saying that money, no matter how it’s spent, will give you a positive return,” Sibilia said. “But I think 95 percent of the people studying money in education will tell you that spending is only as good as what you can buy.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter