Understanding how particles such as electrons travel vast distances in space or how they acquire ultra-high energy has been a long-standing puzzle in astrophysics.

In fact, physicists’ picture of the manner of energy propagation in the universe is still not fully clear. On January 13, researchers with the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University in the US and Northumbria University in the UK made an important finding that mitigates some of the fuzziness.

In their paper, published in the journal Nature Communications, the researchers reported that collisionless shock waves, which are easy to find throughout the universe, could be the cosmic engines driving subatomic particles in space to extreme speeds.

The team found these shock waves to be among nature’s most powerful particle accelerators.

Scouting the plasma

These shock waves are born in plasma — a gas of charged particles that can conduct electricity and interact with magnetic fields.

The study was based on data from three of NASA’s space-based data sources: the Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission, the Time-History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms (THEMIS) mission, and the Acceleration, Reconnection, Turbulence, and Electrodynamics of the Moon’s Interaction with the Sun (ARTEMIS) mission.

Based on their analysis, the researchers have proposed a comprehensive new model that includes recent theoretical advancements in physics that they have said can explain the acceleration of electrons in collisionless shock environments.

When you shout at your friend across a field, say, the sound waves travel through the air between you two to reach your friend’s ears. The travel happens at a speed equal to the speed of sound through the atmosphere. But sometimes, it’s possible to transmit waves at faster than the speed of sound through the atmosphere — these are called shock waves.

In general, the density of a plasma is far lower than that of the three most common states of matter: solid, liquid, and gas. Another way of saying this is that the average distance between the constituent particles of plasma is much greater than in a dense solid, liquid or gas.

But in plasma, the interparticle distance is even greater than the range of interparticle forces, which means any particle in the plasma rarely collides with another. Instead the particles interact via the electromagnetic force.

This means a shock wave sent through the plasma will transfer its energy forward not by smashing the particles together but by riding the electromagnetic forces between them.

The electron injection problem

Astronomers have found shock waves in outer space near pulsars and magnetars, in the hot disks of matter surrounding black holes, and other similar energetic objects. When a sufficiently massive star explodes into a supernova, it throws out a significant amount of energy. If the star is surrounded by a plasma, the shock front will essentially propagate in a collisionless manner.

The electrons within the plasma itself will be pushed forward at a speed that, depending on the circumstances, could be very close to the speed of light. Such electrons are said to be relativistic, since their properties can now be described only by the theories of relativity.

Such shock waves have previously been found to play a key role in producing cosmic rays: streams of high-energy particles travelling through the universe. When one such stream smashes into the earth’s atmosphere, it breaks up into a shower of other particles.

In the new study, the researchers focused on diffusive shock acceleration, a well-known mechanism capable of accelerating electrons to tremendous energies through collisionless shock waves. But there’s a catch: the mechanism requires electrons to have been accelerated to around 50% of the speed of light first before it can propel them even further.

Whether there’s a natural process in the universe capable of providing this first bump — a.k.a. the electron injection problem — has been a long-standing mystery in astrophysics.

Solar wind v. magnetosphere

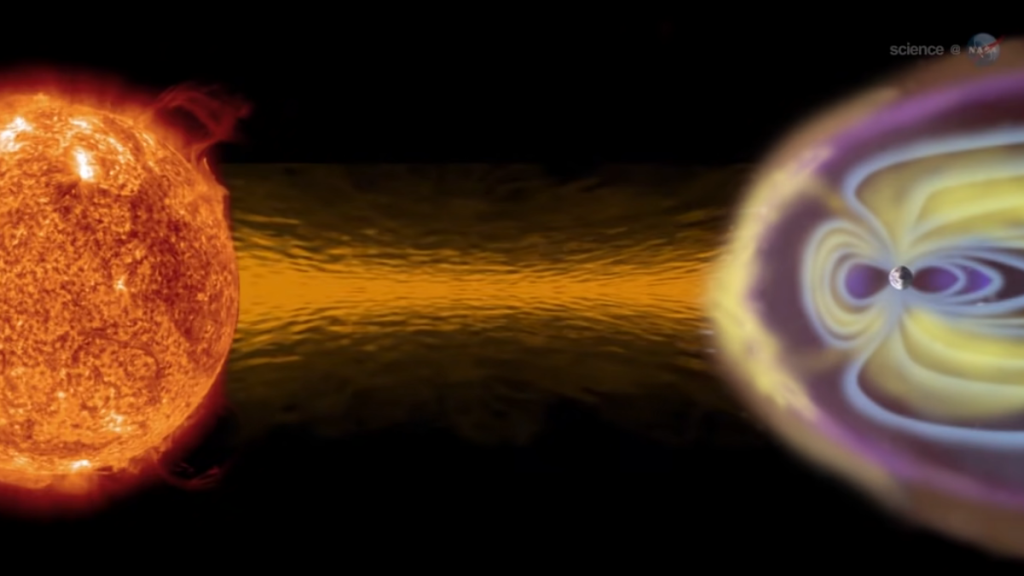

The researchers used real-time data from the MMS, THEMIS, and ARTEMIS missions about how the solar wind interacted with the earth’s magnetosphere and about the upstream plasma environment near the moon. The solar wind is a river of charged particles constantly flowing out from the sun into the solar system.

“One of the most effective ways to deepen our understanding of the universe we live in is by using our near-earth plasma environment as a natural laboratory,” Northumbria research fellow and study coauthor Ahmad Lalti said in a press release.

When the solar wind hits the magnetosphere, it slows down and transfers its energy into a shock wave. The region where this transfer happens is known as the bow shock and its leading area is called the foreshock. The position of the bow shock depends on the speed of the solar wind and its density.

Data collected by the three missions on December 17, 2017, in particular revealed something strange. The team found a transient but large-scale phenomenon upstream of the earth’s bow shock. During this event, electrons in the earth’s foreshock seemed to acquire more than 500 keV of energy. If this was entirely kinetic energy, the electrons would have been moving at around 86% of the speed of light.

This was a striking result given the fact that electrons in the foreshock region typically have just around 1 keV of energy.

According to the researchers, these high-energy electrons were generated by a complex interplay of multiple acceleration mechanisms, including the interactions with various plasma waves and with transient structures in the earth’s bow shock and foreshock. They also excluded the influence of solar flares and coronal mass ejections from the sun at this time.

A cosmic-ray contribution

“In this work, we use in-situ observations from MMS and THEMIS/ARTEMIS to show how different fundamental plasma processes at different scales work in concert to energise electrons from low energies up to high relativistic energies,” Lalti said in the statement. “Those fundamental processes are not restricted to our solar system and are expected to occur across the universe.”

Indeed, the team’s refined acceleration model provides new insights into the workings of space plasma and other phenomena within our solar system.

For example, as the researchers wrote in their paper, scientists believe supernova shocks are responsible for creating cosmic rays — yet it’s possible at least some of them might have been created by the process described in the paper.

In some star systems, they wrote, “under the presence of [gas-giants orbiting very close to their stars], the existence of massive magnetic fields enables our mechanism to potentially sustain” electrons of a million to a billion keV of energy.

“Our results, therefore, imply that a portion of the cosmic ray distribution of relativistic electrons might originate from the interaction of planetary … shocks with typical stellar winds.”

They concluded by asking for more research by the “stellar astrophysics and particle acceleration communities” to verify their idea.

Qudsia Gani is an assistant professor in the Department of Physics, Government Degree College Pattan, Baramulla.

Published – March 11, 2025 05:30 am IST