Last November, a hallway on the first floor of the fine arts building at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, transformed into a contentious forum for an ongoing debate: Should generative artificial intelligence have a place in making art? Can it create meaningful work reflective of the human experience? And should art students be required to learn how to use it?

In the two-plus years since the launch of ChatGPT forced higher education institutions to grapple with how to incorporate generative AI tools into teaching and learning, numerous art schools and departments have taken up the charge. So it wasn’t a first when a visual arts professor at UMBC last semester required his animation students to create three thumbnail sketches of different characters using generative AI tools.

But the assignment incited unexpected backlash. And now, hundreds of UMBC students want to ban generative AI in the university’s art classes.

“I was trying to prepare my students for these endless shock-wave moments in which a new disruptive technology rolls out and we all have to encounter it, wrestle with it and work with it eventually,” said Timothy Nohe, the UMBC professor who developed the assignment. “I also wanted to prepare them for going into the workforce and into a culture where they’re going to encounter people who will want them to have AI competencies.”

What he wasn’t prepared for, however, was other students’ angry reactions to the resulting pieces, which he exhibited in a well-trafficked hallway.

‘AI Is Not Art’?

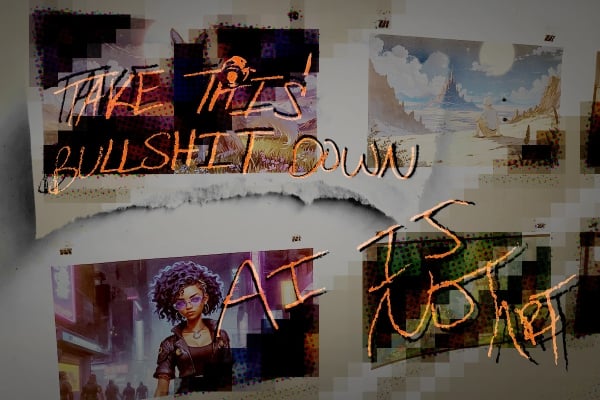

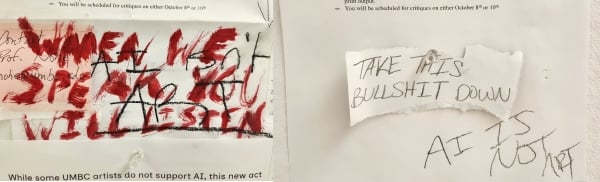

One student scrawled the words “Take This Bullshit Down. AI Is Not Art” on a description of the assignment tacked up next to the printed pieces. Another wrote in scratchy red paint, “When we speak you will listen.” Others unpinned the corners of the prints, causing them to droop on the wall.

Vandalism scrawled on the posted assignment description.

But the backlash didn’t stop there. And what’s transpired since is proving the value of careful, constructive dialogue between professors and their students, including those who are fearful and anxious that AI is cheapening creativity and threatening their job prospects.

“We need to really talk and listen to students, because we’re not on the same page,” said Gary Rozanc, chair of the visual arts department at UMBC. “Part of why faculty aren’t having as much anxiety around generative AI is because of our experience through history. Many of us have lived through some of those changes and studied history that tells us this is just another thing we have to adapt to. We forget that our students do not have that perspective.”

Rozanc attempted to deploy some of that historical perspective to address “the repeated vandalism” of the AI art exhibit in an email to all visual arts students last November.

“What is particularly disturbing about the recent vandalism is that whoever is doing it is declaring that they are the sole arbiter of what is and is not art and demanding censorship,” Rozanc wrote. “While there may be others who agree with the sentiments expressed, I would like to remind you of two key moments in history where a sole arbiter made the decision of what is and is not art.”

His examples? Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany’s persecution of the Bauhaus, which led to the exile of other artists, and Joseph Stalin’s declaration that only social realism is art, which also led to artists’ exile.

“Unlike the fascist regimes that forced these artists and designers into exile, America was a safe place where ideas were not persecuted but debated,” he wrote. “There is certainly a debate to be had around the use of AI in art creation, and I encourage you to bring up the topic in the classroom and with your peers with an open mindset fitting for a liberal arts campus.”

But instead of inspiring a more nuanced perspective on the dangers of policing certain art forms, the fascism references only escalated student outrage.

“That caught people off guard,” said Clare Mansour, a graphic design student at UMBC who was not part of the class that was assigned the AI art project. “Me and a few of my friends decided we had to say something.”

They wanted to make known their stance that generative AI shouldn’t be a part of making art, but not with vandalism.

“A lot of people say generative AI is the future, but I simply don’t believe that,” she said. She worries that it could damage students’ artistic skills. “The impression students were getting is that they were paying for a class where they were just taught to type a prompt in and submit it without doing anything. That upset people.”

That’s why Mansour—who admitted she wasn’t completely clear on the particulars of Nohe’s assignment—and other UMBC students wrote a petition two months ago calling on the visual arts department to prohibit the use of generative AI tools.

“AI image-generation leaves no room for personal expression or creative thought,” reads the petition, which characterizes generative AI as a form of plagiarism and had 841 signatures as of Sunday. “Requiring the use of this technology eliminates opportunities for students to challenge themselves creatively.”

While the petition disavows the vandalism, it also asserts that Rozanc’s “analogy between the vandalism and the actions of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin” was “completely unwarranted and offensive.”

Rozanc told Inside Higher Ed he regrets those comments, which only distracted students from the questions at hand. “Whether it was accurate or not, the baggage attached to it was too much,” he said. “In hindsight, I escalated it by going to the extreme example instead of simply saying, ‘Let’s have an open dialogue.’”

Making Space for AI ‘Sorrow’

But the bottom of his now-infamous email did call for more dialogue, and Mansour and some of the other concerned students were heartened by what came next.

The following week, Rozanc set up a gallery space right next to the original exhibit, inviting students to write short messages about their thoughts on AI and art and post them on the wall. And many of them did.

Dozens of students wrote and exhibited their concerns about using AI to make art.

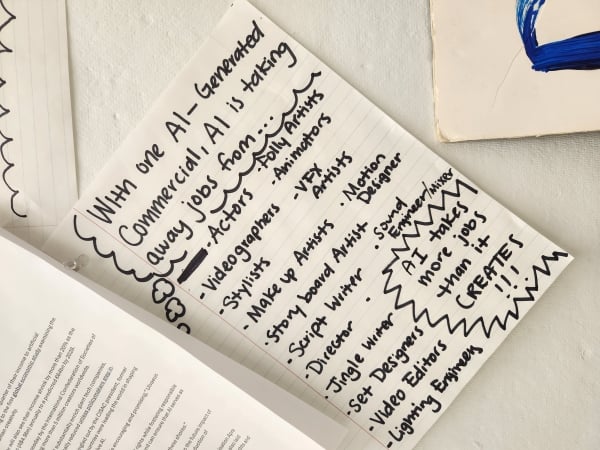

“Please don’t include gen AI in visual arts without teaching the hell out of ethics,” one poster said. Another handwritten note said “AI takes more jobs than it creates!!” claiming that a single AI-generated commercial puts numerous professionals out work, including actors, motion designers and video editors.

One student wrote about their worry that AI is taking artists’ jobs.

“They were quite thorough and quite far-reaching in their concerns about how generative AI was going to affect not only their professions, but the environment and society in general,” said Rozanc, who is planning a student forum to help develop a more comprehensive AI policy for visual arts courses. “I truly hope this is going to be turning into lemonade.”

Mariel Chavez-Barragan, a fine arts major who completed the AI art assignment, said that although she didn’t personally object to it, she appreciated the department’s response to the whole ordeal.

“All of this was about the close-mindedness and immaturity of the student body,” she said. “But I am thankful that the department decided to give the space for students to let themselves speak out however they want until the tension dialed down.”

From Chavez-Barragan’s perspective, knowing how to use AI tools is a skill to make herself more marketable, not a threat to her future.

“It’s necessary at this point to know at least a little bit about how AI works,” she said. “The industries—gaming, animation and film—are all using AI. It’s beneficial for students to know how certain AI programs work, just like any other program an artist would use. But it’s up to students to decide if we want to do something more with it.”

Rick Dakan, a creative writing professor and AI coordinator at the Ringling College of Art and Design in Sarasota, Fla., said exposing art students to AI can help ease some of the fear students at UMBC and elsewhere may have.

“We want students to be able to make informed decisions about AI that are relevant to their ethical stance and creative practice,” he said. “When students have an opportunity to learn how AI works at a fundamental level and do something useful or interesting with it, they quickly learn both its limits and capabilities, and their comfort level with it rises.”

While banning or ignoring AI isn’t realistic, Dakan said educators also need to make space for the “sorrow” associated with the rise of AI and its ability to mimic art forms that were once considered the province of society’s most gifted artists and writers.

“Students know there’s nothing to be done, and that this is coming and it’s going to impact each other,” Dakan said. “No one comes to be an illustrator at art school for any reason stronger than they love to draw. It’s disruptive and scary. It strikes at some of our identities as creators.”