Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Data from Sept. 18 to Oct. 17, 2024

Along the sparkling coast of Southern California, a string of landslides creeping toward the sea has transformed the wealthy community of Rancho Palos Verdes into a disaster zone.

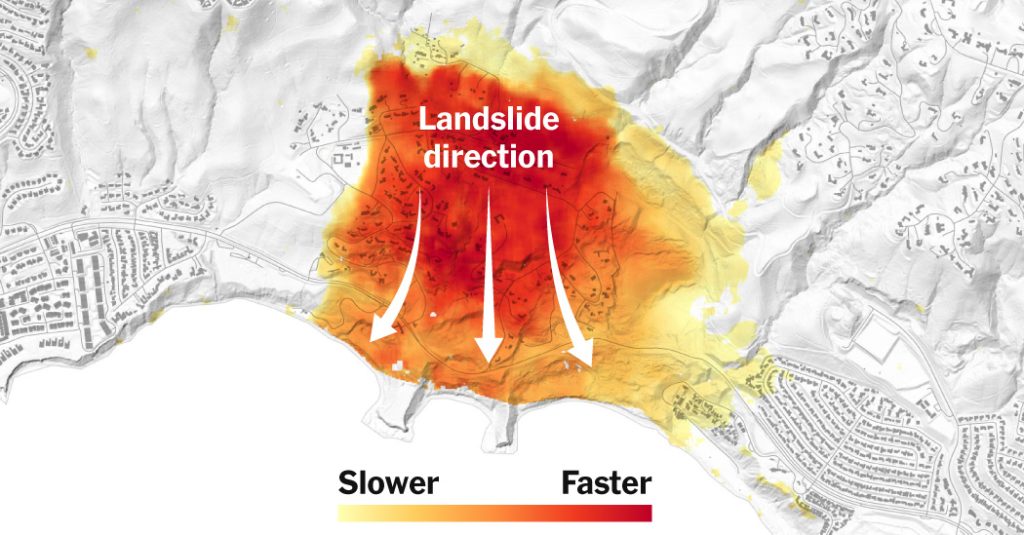

New data from a NASA plane shows the widening threat of these slow-moving landslides, which have destabilized homes, businesses, and infrastructure like roads and utilities. Researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory documented how the landslides have pushed westward, almost doubling in area since the state mapped them in 2007.

The landslides have also sped up in recent years. A month of aerial radar images taken by NASA in the fall revealed how land in the Palos Verdes Peninsula slid toward the ocean by as much as four inches each week between mid-September and mid-October. Before that, a city report showed more than a foot of weekly movement in July and August.

Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Present boundary includes areas where landslides moved faster than one centimeter per week between Sept. 18 and Oct. 17, 2024.

The mass of slides in Los Angeles County, known as the Greater Portuguese Bend Landslide Complex, reactivated in 1956 after road construction destabilized the once-dormant slope. For decades, it slid just a few inches every year. But heavy rain in 2023 and early 2024 accelerated that movement, leading Gov. Gavin Newsom to declare a state of emergency, citing “conditions of extreme peril to the safety of persons and property.”

Homes in Rancho Palos Verdes began collapsing in June and August of 2023. Streets have fissured. Walls have shifted and floors have cracked open to reveal the dynamic earth below. A downed power line related to the slides started a small brush fire in August. A $42 million buyout program helps property owners voluntarily sell and relocate, but homeowner insurance policies do not typically cover landslides.

A stretch of coastline where landslides meet the beach in Rancho Palos Verdes.

Loren Elliott for The New York Times

Damage in a residential area of Rancho Palos Verdes in August.

Loren Elliott for The New York Times

Mitigating such a disaster is extremely expensive. By the end of this fiscal year, the city said it will have spent more than $35 million, almost 90 percent of its general fund operations budget, on addressing the landslide. That includes the installation of 11 wells that have worked to pump out 145 million gallons of groundwater that could further destabilize the slope. The investment has yielded results: The landslide slowed by about 3 percent on average between December and February thanks to the wells and a lack of rain, the city said.

Slow-moving slides are common around the world, and especially in California, where several hundred have been mapped in coastal mountain ranges. Normally moving at a sluggish pace, these slides can grind nearly to a halt during the dry summer months before a wet winter makes them crawl again.

But last summer, the landslide complex in Rancho Palos Verdes exhibited strange behavior when it failed to slow. The best guess for why has to do with a very wet 2023, said Alexander Handwerger, a research scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory who has studied the behavior of slow-moving landslides for well over a decade. Typically triggered tens of meters underground, they remain an ongoing area of research.

“Of all the things we know,” Dr. Handwerger said, “we know the least about what’s happening under the ground.”

Last week, other parts of Los Angeles County faced additional landslides, ones that move quickly, running at meters per second instead of centimeters per week. The National Weather Service in Los Angeles issued warnings for post-fire debris flows — a tangle of mud, rocks and trees that start on burn scars — ahead of heavy rainfall on Thursday. Los Angeles neighborhoods scorched by wildfires like the Eaton and Palisades fires last month faced some of the greatest dangers as those flows hit business and homes in Southern California.

But slower-moving landslides, like the ones in Rancho Palos Verdes, are more predictable. They ooze rather than race. They typically need a season of rain, rather than a single storm, to accelerate. And it’s extremely rare for them to suddenly collapse or slide in a catastrophic way.

It’s unclear what triggers that kind of sudden catastrophe, said Luke McGuire, an associate professor in geomorphology at the University of Arizona. He pointed to one of the few known examples of such an event, in 2017, when the Mud Creek Landslide in Big Sur gave way after eight years of stable sliding. More than 65 feet of rocks and dirt covered a quarter-mile of Highway 1, the scenic drive winding along the California coast.

Experts say that the city of Rancho Palos Verdes probably will not experience that kind of sudden event. “You can never say never, but the likelihood that this would go into a catastrophic movement phase is quite low,” said Dave Petley, a landslide expert who collects global landslide data for the American Geophysical Union. “It’s likely it’ll continue to cause substantial property damage, but the risk of the thing suddenly sliding into the sea and taking everyone with it is not particularly high.”

A 2019 Nature study by Dr. Handwerger showed that the Mud Creek Landslide could have been triggered by a shift from drought to record rainfall. In a warming world, an increase in extreme rain events could cause more landslides to quicken, according to the study.

More precipitation could also cause more landslides to emerge from hibernation into slow-moving slides.

“Rainfall under climate change can wake a landslide back up,” Dr. Petley said, adding that a vast number of dormant landslides with this potential exist across the globe.