Michigan students in the highest-poverty school districts are most likely to learn from teachers who are inexperienced, have emergency or temporary credentials or those who are teaching classes outside their field of expertise, according to a recent report by The Education Trust-Midwest.

For example, teachers in districts with the highest concentrations of poverty are almost three times more likely to be early in their career, with less than three years of experience. And students in these districts are 16 times more likely to learn from a teacher with temporary or emergency credentials than their peers in Michigan’s wealthiest school districts.

“The teacher shortage crisis that we hear a lot about here in Michigan is far worse for our students with the greatest needs,” said Jen DeNeal, director of policy and research at EdTrust-Midwest and lead author of the report.

DeNeal noted that research shows that novice, not fully credentialed teachers are generally less effective in the classroom.

While the national teacher shortage in certain subjects has been well documented as an intractable issue that’s worsened since the pandemic, the EdTrust study released last month uniquely zooms in on district-level data and demonstrates the scope of the problem.

“Having gaps is, of course, not a surprise,” said Michael Hansen, a senior fellow at the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution. “Having gaps of this magnitude is pretty stark.”

DeNeal and her team at EdTrust, which advocates for educational equity with a focus on children who have been traditionally underserved, spent two years analyzing educator workforce data from public and non-public sources, conducting focus groups and reviewing previous research.

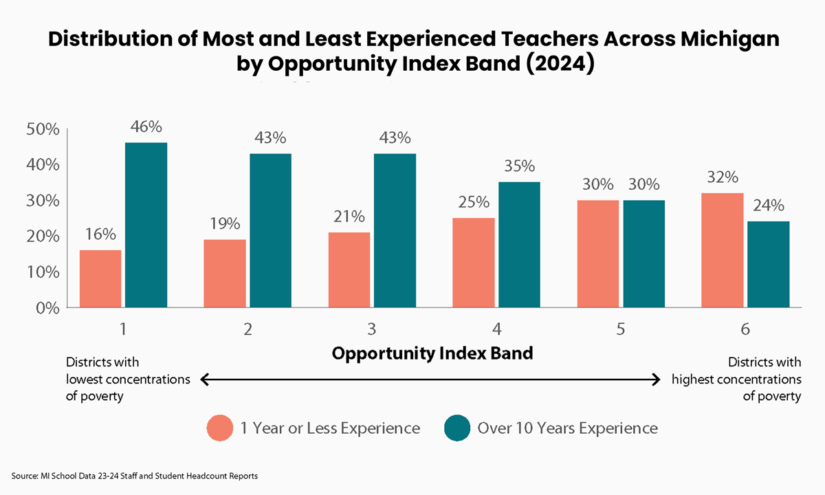

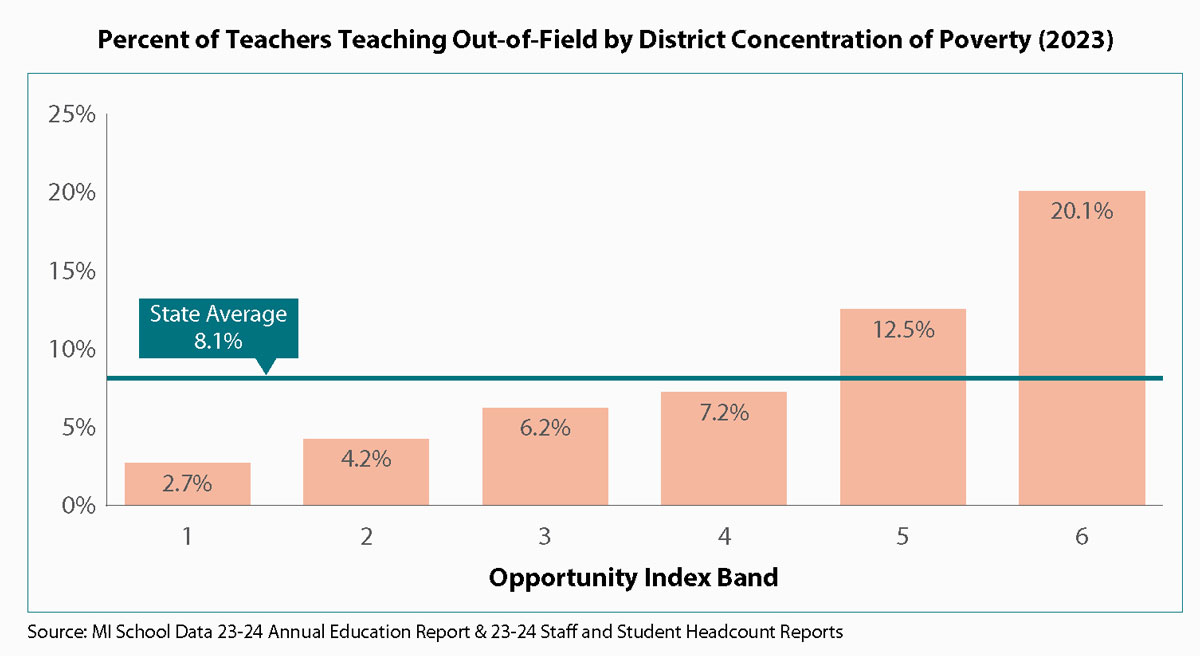

They used Michigan’s Opportunity Index, a state funding formula passed in 2023 that includes an index for concentrations of poverty, to divide school districts into six bands. Band one includes districts with fewer than 20% of students living in concentrated poverty while band six includes districts where 85% to 100% of students live in these conditions.

Researchers then looked at how highly qualified teachers — defined as those who were fully certified with more than three years of experience teaching in their certification or more refined speciality areas — were distributed across these districts.

They found that in the 2022-23 school year, more than 16% of teachers in high-poverty districts were teaching a subject or grade not listed on their license — that’s twice the state average. These districts accounted for more than a third of all out-of-field educators in the state, despite only employing 13.5% of Michigan teachers.

While out-of-field teachers are typically a stop-gap resource preferable to a revolving door of substitutes, they may lack the content knowledge and skills needed to effectively teach, and students who learn from them tend to have less academic growth in that subject. Those with emergency credentials are also able to fill teacher vacancies when more qualified ones aren’t available, though they’re more likely to be rated as “unsatisfactory” or “needs improvement” when compared to other new teachers.

Hansen noted that being trained and fully licensed makes a teacher more likely to provide quality instruction in the classroom, but “it’s no guarantee.” And while these findings do likely point to a “more effective teacher workforce in these more affluent settings, and … a less effective workforce in the high-needs settings, it’s probably not the case that it’s going to be 16 times more effective.”

Yet, “of all these different factors and characteristics that they’re highlighting in this report, experience is the number one that’s documented to show an impact across multiple studies and multiple grades,” he added.

Persistent vacancies may be particularly hard to fill in Michigan, where teacher attrition is slightly worse than the national average, and teacher turnover is far higher for students living in poverty. For example Black students, who account for only 18% of the statewide student enrollment, make up 45% of enrollment in schools where teachers were most likely to leave.

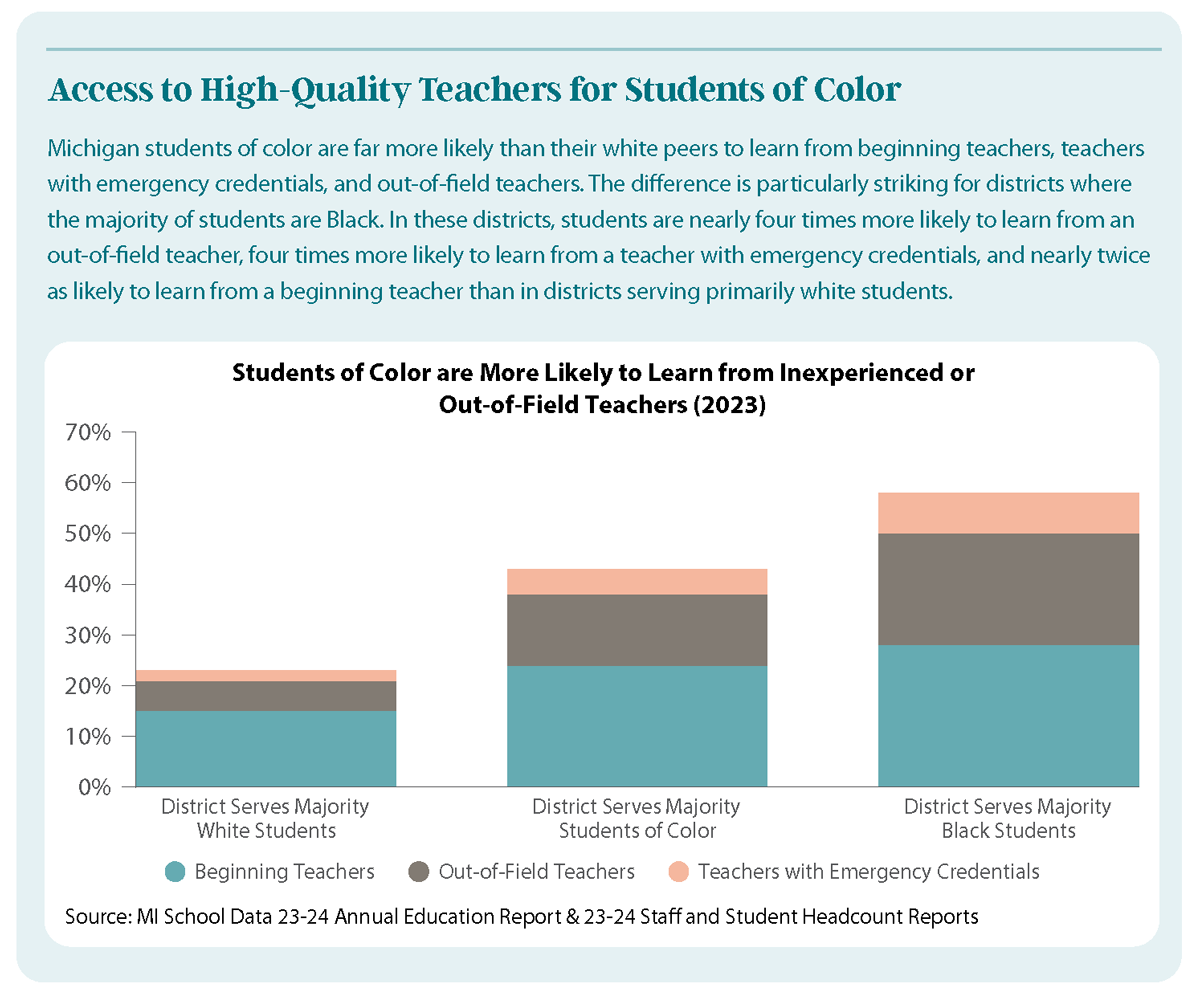

In districts where a majority of children are Black, students were nearly four times more likely to learn from an out-of-field teacher, four times more likely to learn from a teacher with emergency credentials and nearly twice as likely to learn from a beginning teacher than in districts serving primarily white students.

In focus groups, teachers pointed to a number of factors contributing to the shortage, including the pandemic, discipline challenges and chronic absenteeism. They also reported that their classrooms are overfilled, they have less one-on-one time with students and less planning time because they’re being called on to substitute teach. One issue, though, came up again and again: pay.

“We’re not competitive regionally and we’re not terribly competitive nationally,” DeNeal said.

Between 1999 and 2019, Michigan’s inflation-adjusted teacher salary fell more than 20%, representing the second-largest teacher salary decline in the country. First-year teachers in Michigan earned, on average, about $39,000 a year, rendering it 39th nationally and last among Great Lake states. And researchers found that teachers in the wealthiest district are paid, on average, about $4,000 more annually than those in the poorest districts.

This is exactly the opposite of what the pay structure should look like, according to Dan Goldhaber, an education researcher at the American Institute of Research and the University of Washington. He argued that teachers in more challenging environments should be paid more than their peers to compensate for the additional hurdles.

“I don’t think this is an issue where we need a lot of research to know that this problem exists and to know at least what some of the potential solutions are,” he said. “This is an issue where the politics I think make it challenging to implement at least some of the solutions.”

DeNeal said that although these challenges are “troubling and extremely persistent, they are not insurmountable.”

The report put forward five recommendations, based on teacher focus groups and previous research: prioritize fair and equitable funding; improve state education data systems to increase transparency; provide greater support for school administrators; focus on making teaching an attractive and competitive career and increase access to high-quality professional development for teachers.

Thomas Morgan, spokesperson for the Michigan Education Association, emphasized the importance of incorporating teacher voice in the solutions.

“When you want to know what to do to fix our schools,” he said, “the first people you should talk to are people working on the front lines: those teachers working in our schools. They see things, they live it, they breathe it and they should be consulted.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter