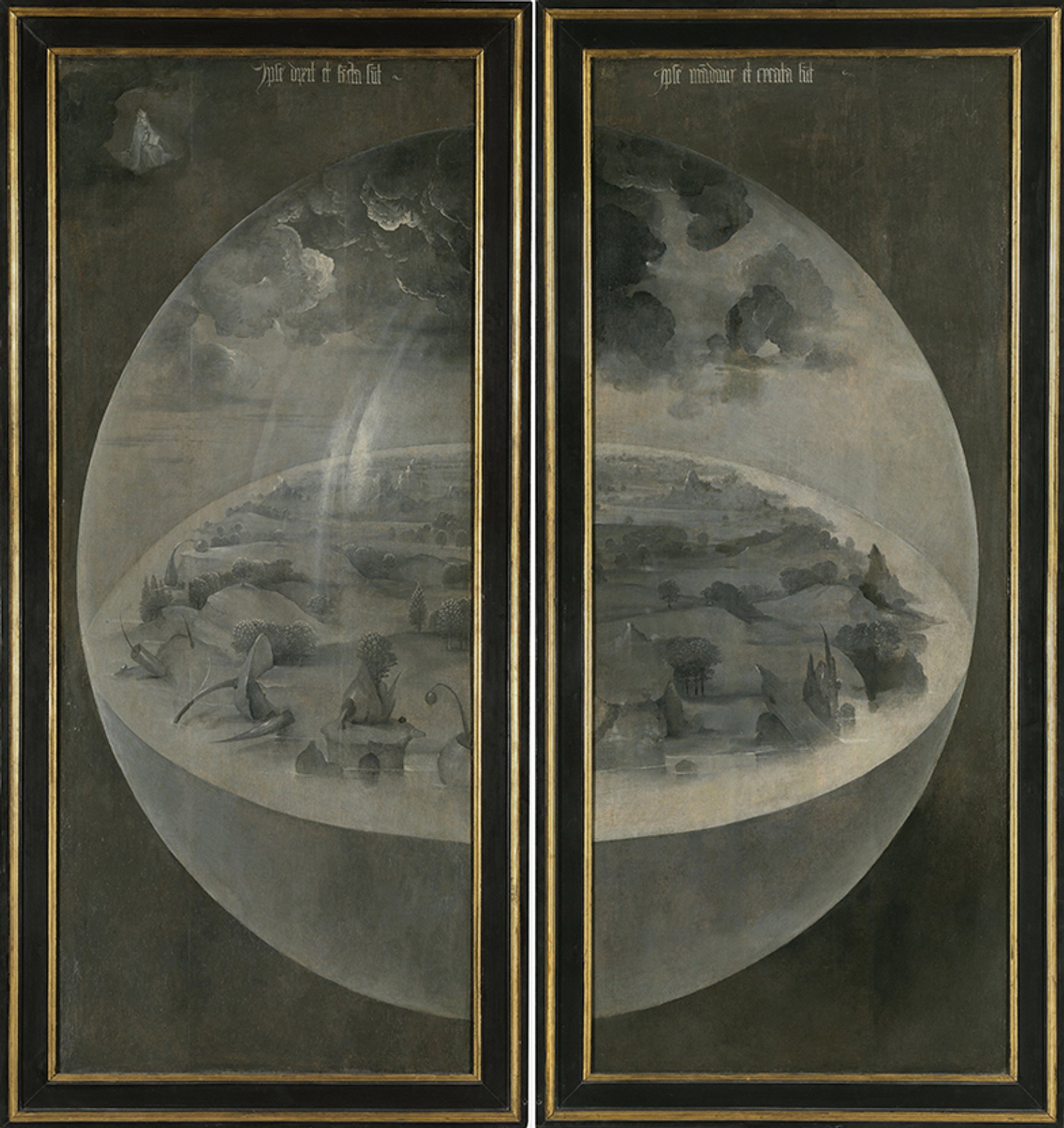

Fernando Álvarez de Toledo y Pimentel, Duke of Alba (1507-82), the Spanish crown’s henchman in the Netherlands, wanted nothing more than to lay his hands on Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights. The magnificent triptych, which Bosch (born around 1450, died 1516) completed around 1500, is unique even in the painter’s own oeuvre. With closed wings, it shows the newly created world as a dark island drifting in an ocean of pale grey. When open, though, light breaks through and a carnival of colour unfolds before the viewer’s eyes, the effect mainly of the triptych’s central panel: throngs of nude humans frolicking, as if their lives depended on it, riding horses, pigs, birds and other creatures, hiding inside shells and other bizarre receptacles, munching on giant pieces of fruit, cavorting with sea monsters—and sticking flowers up someone’s backside. In Art in a State of Siege, Joseph Leo Koerner memorably sums up the panel’s main narrative: “No one says ‘No’ in this garden.”

But Doomsday is right around the corner, although the two side panels—one depicting Adam and Eve before the fall, the other, souls writhing in hell—can do little to offset the impact of that delicious central panorama of sinful pleasures. No wonder that at least one Bosch scholar, Wilhelm Fraenger (1890-1964), referred to frequently by Koerner, thought that Bosch’s work was not an indictment but a celebration of lust, inspired by the Adamites, a secret Christian sect originally from North Africa who were convinced that humans should follow their desires.

Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (around 1500), in its closed state © Fine Art Images/Heritage-Images

A professor of art history at Harvard University, Koerner is also a lively, engaging writer. He tells us that, in the early 16th century, copies of Bosch’s fantastical pictures circulated all around Europe. Some of them were fakes, roasted into deceptive authenticity over the forgers’ fireplace. But the Duke of Alba would accept no substitutes. When, in 1567, his men invaded the Nassau palace of William the Silent, Prince of Orange, the head servant refused to tell them where the painting was hidden. Koerner quotes a contemporary account of what happened next: “They hoisted him on high with a weight of 100 pounds hanging from his feet until his hands touched the pulley, then they added weight of 150 pounds.” Just in case, they also burned the man and broke his limbs. Who needs hell when people can inflict such pain on each other? The duke got his prize; Bosch’s unconcerned sinners are now frolicking at the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

Art in a State of Siege, based on the author’s E.H. Gombrich lectures at London’s Warburg Institute in 2016, is a captivating, often challenging work. Koerner is as intent on taking possession of Bosch’s painting intellectually as the Duke of Alba was desirous of owning it in the flesh. “Bosch’s art gave form to every viewer’s imagined enemy in every here and now,” writes Koerner. In his opinion, the siege mentality he finds expressed there—portraits of humankind on the brink, made for fretful onlookers—may serve as a key for understanding other works of art, notably the haunting Self-Portrait in Tuxedo (1927) by the German Modernist painter Max Beckmann (1884-1950), as well as the animated drawings of the South African multimedia artist William Kentridge (born 1955).

Sigmund Freud believed that we spend our lives in a permanent state of siege … an opinion Koerner appears to share

Writing about triptychs, Koerner hands us his own. He has, he suggests, a different relationship with each of the three artists discussed in his three chapters. While Bosch has been the subject of his scholarly curiosity for decades, Beckmann’s Self-Portrait, in the collection of Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, often serves as the centrepiece of Koerner’s museum tours for visitors and students. And when the author, many years ago, went to his first Kentridge exhibition, the South African’s works on paper reminded Koerner of images created by his father, a Viennese-born artist and Holocaust survivor. Art in a State of Siege includes a reproduction of Henry Koerner’s striking The Skin of Our Teeth (1946, the Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska-Lincoln), which depicts naked Boschian figures digging through the rubble of a bombed-out apartment.

Sigmund Freud believed that we spend our lives in a permanent state of siege, beleaguered not by actual devils but by those of our own making: an opinion Koerner appears to share, although his demons are those created by other people; Bosch lived in a world dominated by military sieges, with Constantinople (Istanbul) falling to the Ottomans in 1453, just around the time he was born; Beckmann saw his art condemned as “degenerate” by the Nazis; and Kentridge came of age in the living hell of South African apartheid. Beckmann’s vivid triptych Departure (1932-35, Museum of Modern Art, New York), finished after the Nazi takeover of Germany, contrasts a central panel featuring a king and his entourage adrift on a blue ocean with side panels portraying humans in distress, blindfolded, gagged, and bound. Calling Beckmann’s works “a beacon for endangered souls”, Kentridge has, for several decades, carried with him a postcard reproduction of the German artist’s oil on canvas Death (1938).

As laid out in the book’s introduction, Koerner’s idiosyncratic method, bouncing between centuries and countries, and shuttling back and forth between art, history, politics and literature, draws inspiration from the art historian Aby Warburg’s “image atlas”, which Warburg compiled after his three-year confinement in a psychiatric clinic: creative collages of pictures from very different sources pinned to large panels. The connections and constellations Koerner proposes in his book may not always be self-evident: there is no detour he will not take, no dark tunnel he will not enter. But the results are invariably enlightening. For example, Fraenger’s friendship with the jurist and Nazi apologist Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) leads Koerner to include several revelatory pages on the traumatic wartime experiences of Schmitt’s correspondent Ernst Jünger (1895-1998), the conservative writer and extoller of apocalyptic masculinity, who also turned to Bosch for analogies.

Art in a State of Siege, leisurely, expansive and stunningly erudite, is not the work of a besieged writer. Nor is it a book written for besieged or impatient readers. There are no definite rewards beckoning at the end, no comforting generalisations that timeless art might proffer relief to a mind in distress. Let us remember that Bosch’s triptych spoke to Nazis as well as to their victims: to Schmitt, who used his theory of the “state of exception” to justify, as perfectly constitutional, the horrors of Hitler’s Third Reich; and to Beckmann, whom that same Reich catapulted into exile.

Among the artists and thinkers discussed in Koerner’s book, Hieronymus Bosch, I believe, has the last laugh. It has been said that the famous Tree-Man pictured in a side panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights could be Bosch’s self-portrait. And why would an artist who painted on wood and whose adopted last name (an abbreviation of his native city, ’s-Hertogenbosch) meant “wood” in Dutch, not sometimes wish that he were a piece of wood too, a tree perhaps—firm, stable, rooted in a world of chaos and turmoil? Granted, in Bosch’s triptych the ambiguous Tree-Man is stuck in hell. But if one takes a second look at that creature, as he thrusts his bottom into the viewer’s face, it might seem that Tree-Man is “mooning” us. And over his lips plays, ever so slightly, the ghost of a smile.

• Joseph Leo Koerner, Art in a State of Siege, Princeton University Press, 408pp, 32 colour & 103 b/w illustrations, $37/£30 (hb), published 4 February/ 4 March

• Christoph Irmscher is a critic and biographer