New research led by a York University professor sheds light on the earliest days of Earth’s formation and potentially calls into question some earlier assumptions in planetary science about the early years of rocky planets. Establishing a direct link between Earth’s interior dynamics occurring within the first 100 million years of its history and its present-day structure, the work is one of the first in the field to combine fluid mechanics with chemistry to better understand Earth’s early evolution.

The study is published in the journal Nature.

“This study is the first to demonstrate, using a physical model, that the first-order features of Earth’s lower mantle structure were established four billion years ago, very soon after the planet came into existence,” says lead author Faculty of Science Assistant Professor Charles-Édouard Boukaré in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at York.

The mantle is the rocky envelopment that surrounds the iron core of rocky planets. The structure and dynamics of Earth’s lower mantle play a major role throughout Earth’s history as it dictates, among others, the cooling of Earth’s core where Earth’s magnetic field is generated.

Boukaré says that while seismology, geodynamics, and petrology have helped answer many questions about the present-day thermochemical structure of Earth’s interior, a key question has remained: How old are these structures, and how did they form? Trying to answer this, he says, is much like looking at a person in the form of an adult versus a child and understanding how their energetic conditions will not be the same.

“If you take kids, sometimes they do crazy things because they have a lot of energy, like planets when they are young. When we get older, we don’t do as many crazy things, because our activity or level of energy decreases. So, the dynamic is really different, but there are some things that we do when we are really young that might affect our entire life,” he says. “It’s the same thing for planets. There are some aspects of the very early evolution of planets that we can actually see in their structure today.”

To better understand old planets, we must first learn how young planets behave.

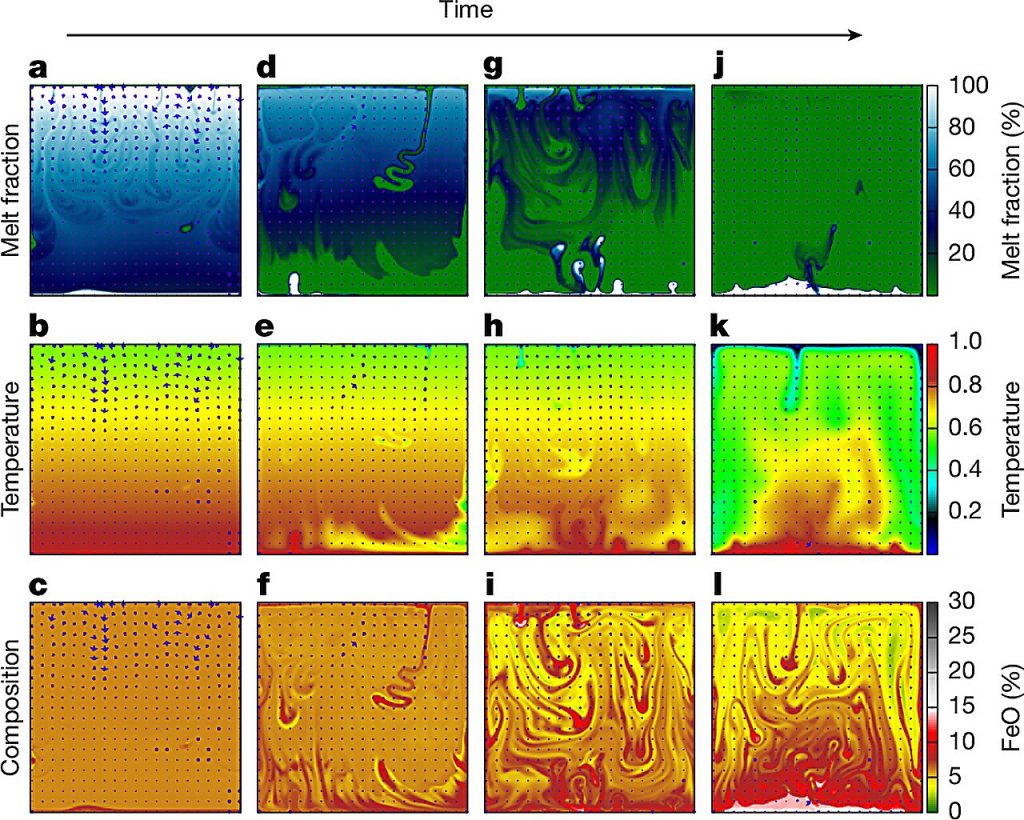

Since simulations of Earth’s mantle focus mostly on present-day solid-state conditions, Boukaré had to develop a novel model to explore the early days of Earth when the mantle was much hotter and substantially molten, work that he has been doing since his Ph.D.

Boukaré’s model is based on a multiphase flow approach that allows for capturing the dynamics of magma solidification at a planetary scale. Using his model, he studied how the early mantle transitioned from a molten to a solid state. He and his team were surprised to discover that most of the crystals formed at low pressure, which he says creates a very different chemical signature than what would be produced at depth in a high-pressure environment. This challenges the prevailing assumptions in planetary sciences about how rocky planets solidify.

“Until now, we assumed the geochemistry of the lower mantle was probably governed by high-pressure chemical reactions, and now it seems that we need to also account for their low-pressure counterparts.”

Boukaré says this work could also help predict the behavior of other planets down the line.

“If we know some kind of starting conditions, and we know the main processes of planetary evolution, we can predict how planets will evolve.”

More information:

Charles-Édouard Boukaré, Solidification of Earth’s mantle led inevitably to a basal magma ocean, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08701-z. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-08701-z

Provided by

York University

Citation:

New research sheds light on earliest days of Earth’s formation (2025, March 26)

retrieved 26 March 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-03-earliest-days-earth-formation.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.