After months of uncertainty about the future of federally funded research, the National Institutes of Health this month started canceling grants it deemed “unscientific.”

So far, that includes research into preventing HIV/AIDS; managing depressive symptoms in transgender, nonbinary and gender-diverse patients; intimate partner violence during pregnancy; and how cancer affects impoverished Americans.

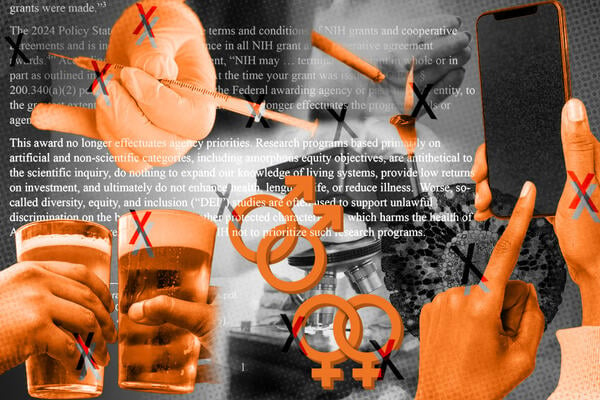

In letters canceling the grants, the NIH said those and other research projects “no longer [effectuate] agency priorities.”

But the world’s largest funder of biomedical research didn’t stop there. The agency went on to tell researchers that “research programs based primarily on artificial and nonscientific categories, including amorphous equity objectives, are antithetical to the scientific inquiry, do nothing to expand our knowledge of living systems, provide low returns on investment, and ultimately do not enhance health, lengthen life, or reduce illness,” according to a March 18 letter sent to the University of Nebraska at Lincoln.

Katie Bogen, a Ph.D. student in the clinical psychology program at UNL, found out via the letter that NIH was canceling the $171,000 grant supporting her dissertation research. She was planning to explore the links between bisexual women’s disclosure of past sexual violence experience to a current romantic partner and subsequent symptoms, including traumatic stress, alcohol use and risk for violence revictimization within their current relationship. She started work on the project last May and was set to start data collection at the end of this month.

The NIH told Bogen and other researchers that “so-called diversity, equity, and inclusion studies are often used to support unlawful discrimination on the basis of race and other protected characteristics, which harms the health of Americans,” and that NIH policy moving forward won’t support such research programs.

“No corrective action is possible” for Bogen’s project, because “the premise of this award is incompatible with agency priorities, and no modification of the project could align the project with agency priorities.”

Last week, Bogen, who told Inside Higher Ed that she was inspired to pursue this topic because she herself is a bisexual woman with a trauma history, posted on TikTok about the termination letter.

She received thousands of comments and messages lamenting the loss of her work, with some characterizing the letter’s language as “appalling” and “horrifying.” Another commenter, who identified “as a bi femme who has survived the specific harm you’ve been studying,” told Bogen their “heart is broken” for her and other researchers “and all the folks who could be helped by the studies being defunded.”

Inside Higher Ed interviewed Bogen for more insight into her research and what the NIH’s abrupt cancellation of her and other projects means for public health and the future of scientific discovery.

(This interview has been edited for clarity and style.)

Q: What got you interested in researching intimate partner violence prevention for bisexual women? Why do you believe it’s an important line of scientific inquiry?

A: We know that bisexual women are at an elevated risk of experiencing intimate partner violence and sexual harm. We also know they have higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder after these experiences compared to other people, and that they have greater and more problematic high-risk alcohol use afterwards. A key part of the process of meaning-making after the experience of violence is disclosure because of ambient bi-negativity. Bisexual people’s disclosure processes are often burdened by anti-bisexual prejudice.

For example, if you’re a bisexual woman who’s experienced violence at the hands of a woman partner, and you disclose that to a man partner that you’re seeing now, that man partner might say, “How much did she really hurt you?” If you’re a bisexual woman who’s now with a woman and you disclose violence perpetrated by a man, your woman partner might say something like, “This is what you get for dating men. We all know better than to date men.”

Katie Bogen is a fifth-year clinical psychology Ph.D. student at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln

So much of the disclosure research on sexual violence victims has been done with formal support providers like police or campus security or therapists, and then informal support providers like friends or parents or siblings. But very little research has documented the exposure process with intimate partners, which seems like a gap, given that intimate partners can then choose to sort of wield that insight or knowledge for good—or for harm.

I want to study how to intervene so that they don’t develop severe post-traumatic stress and problematic drinking. And this is particularly important because problem drinking is a risk factor for revictimization, and so bisexual women have all of these factors working against them that contribute to the cycle of revictimization and chronic victimization over their life span.

Q: Can you describe the process of applying for this NIH grant?

A: In 2022, I had just finished my second year of graduate school when a colleague of mine sent me a funding opportunity from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism that had a notice of special interest on the health of bisexual and bisexual-plus people.

We haven’t even been able to recruit our participants and I have none of the data.”

I worked very hard for a year on my application. It was the first grant I wrote as a [principal investigator]. I submitted to NIH, and a kind of miracle happened—I scored a 20 on this grant, which means my very first grant being written up as a PI got funded on the first round of peer review, which is almost unheard-of.

Q: How much of the project had you finished before receiving the termination notice?

A: I started work last May. I’ve hired and trained an entire lab of undergrads.

I’ve already done the literature reviews with the help of my undergraduate team and put together and tested the Qualtrics surveys. We set up backup safety measures in case the online surveys were infiltrated by bots or false respondents. The amount of literature I’ve read and the foundational conference presentations and analysis that I’ve run using other available data sets has been an immense labor.

It has been a productive 10 months. The things that this research has made possible for me—not only as a student and trainee, but as a scientist and as now a mentor helping to train the next generation of scholars—cannot be understated.

But we haven’t even been able to recruit our participants and I have none of the data. We were slated to begin data collection on March 31, and it’s a shame that will no longer happen.

Q: The NIH’s termination letter said your project is “antithetical to scientific inquiry” and “harms the health of Americans.” What was your reaction to that characterization of your work?

A: It hurts to hear that your work isn’t scientific. But it almost made me laugh because it’s so revelatory of the ignorance of folks in positions of power to claim that the work that I’m doing—that my colleagues are doing, that my mentors have taught me to do, that other folks in a field of doing—is ascientific and itself violence.

To me, the language in the letter is an example of DARVO, which is a rhetorical abuse tactic that stands for deny, attack, reverse victim and offender. They’re saying that what I’m doing isn’t scientific, and that they’re actually trying to uphold the standards of science, and by me focusing on these marginalized groups, I’m harming, quote unquote, real or regular Americans.

[The termination letter] almost made me laugh because it’s so revelatory of the ignorance of folks in positions of power to claim that the work that I’m doing … is ascientific and itself violence.”

Q: How does your work benefit society broadly?

A: Even if we take queerness out of the equation in this model, we are still garnering insight and understanding of the mechanism of post-traumatic stress, alcohol use and intimate partner violence for people in general. We’re getting a deeper understanding of how discussing sexual violence with a partner fundamentally changes that relationship, what is perceived as potentially acceptable in that relationship, norms of conflict within that relationship and sexual norms within that relationship.

Being able to investigate questions like this and enact scholarship like this could be a balm to some of the self-blame and shame that survivors are experiencing. And when research like this is able to reach health-care providers, public health improves, people become safer and we’re better able to protect folks from things like intimate partner violence, revictimization and sexual revictimization, which is endemic in our society.

Q: Given that this research grant was a central piece of your plan to complete your dissertation, how does its abrupt cancellation complicate your path toward degree completion?

A: I now have to work with my mentors to generate a new dissertation proposal and send it to my committee and get it reapproved, which means I have to access data sets at my institution that have either already been collected or that are safe from future rounds of cuts like this.

I believe I’m being intimidated [by the NIH] into taking the data that are already available, rather than collecting data with more specificity, which means the accurate data answering these research questions is tampered. I don’t necessarily want to go to a data set that was collected on, for example, masculinity and violence perpetration, and try and string together a similar enough model to pass the proxy of what I wanted. That’s poor scholarship.

It’s something a lot of scholars who are dealing with this crisis are facing now. How does that further marginalize the populations we’re aiming to serve if we’re trying to presume or assume that data on different populations? It creates this ethical and academic quandary.

Q: How might this termination affect your career in the long term?

A: I have a demonstrated record of receiving grant funding on my own, which is a difficult thing to demonstrate when you’re still a trainee or you’re still a student. It makes folks more competitive for postdocs, research-oriented internships or research jobs at bigger research institutions down the line. If I wanted to work at an academic hospital, it shows that I’ll be able to bring in grant funding.

But now I have this really sad line on my CV. I had to write several asterisks that the grant closed early, and I just have to hope that people who are reviewing my CV later know what that means—that the grant closed early, not because of my failure to complete the research, but because we have the infiltration of antiscientific thought in the federal government that forced a number of grants to close early.

It doesn’t stop at political science, psychology or even economics. It has legs and encroaches and creeps into biophysiological sciences and neuropsychology. It leaves no science safe.”

Q: How does your situation speak to any concerns you might have about the broader environment for science in this country right now?

A: We’re in this identity war moment, and it’s not based on anything but people’s own prejudice and bias and a sense of being victimized because they no longer have access to the power they used to. This is an attempt to recollect and to narrow who has that power, which has frightening implications across the board.

It doesn’t stop at political science, psychology or even economics. It has legs and encroaches and creeps into biophysiological sciences and neuropsychology. It leaves no science safe.