I was grading assignments for an undergraduate course in memoir writing when I experienced a severe crisis of faith regarding the future — of academia, of writing, of thinking. I’d asked my students to write about an obsession, telling their life story through the lens of a pop-culture fixation. This assignment invariably produces a few surprising, insightful and energetic pieces from students who’ve never been asked to take their own interests seriously before. This time, however, I received a 2,000-word submission defining “obsession,” citing the D.S.M.-5 and multiple online sources, all written in the trademark flat, lifeless prose of ChatGPT.

Earlier this month, OpenAI revealed a new version in training mode that, at least according to the company’s chief executive, Sam Altman, is “good at creative writing.” It’s not clear when this new version might be released, but as a longtime instructor of freshman composition, I’m already well aware of the scourge of artificial-intelligence-assisted cheating going on in writing classes of all sorts. I can even sympathize, to an extent. Students get overwhelmed, they panic and resort to the plagiarism machine. These same students have been inundated with A.I. boosterism, and have no doubt encountered overly credulous news reports full of misleading claims about how miraculous A.I. tools can be.

But a creative writing student using A.I.? In a memoir writing class? I have to wonder what you are saying about your life if even you can’t be bothered to think about it.

Having written two memoirs, I know the challenges and pleasures of this work, and I want my students to experience those challenges, too. The act of writing a memoir is not just about saying “Look at me,” but rather about enabling yourself and defining who you are, in part by revisiting particularly fraught experiences, analyzing them from all angles and complicating them in the retelling. This process is — and I don’t say this lightly — an act that makes the author more fully alive.

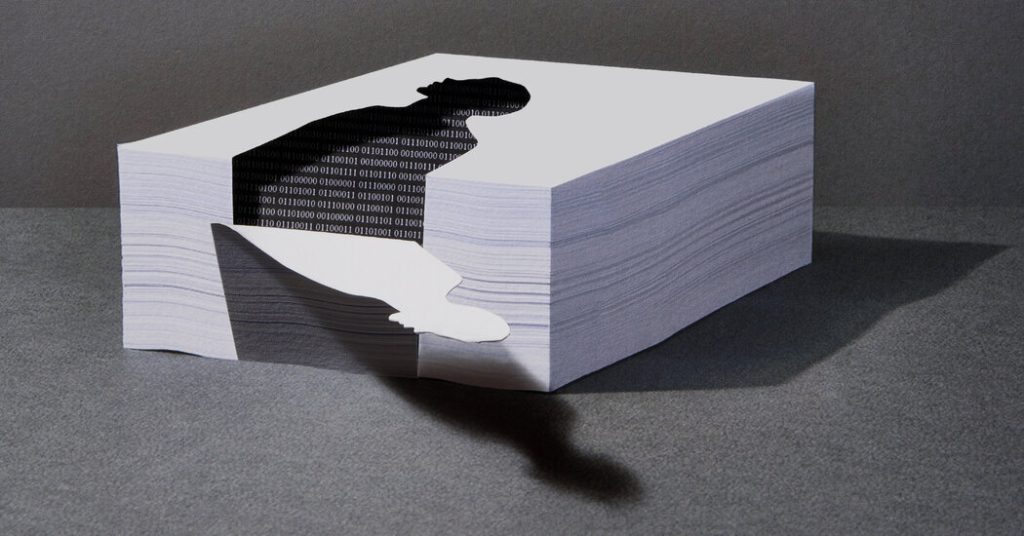

To farm out this task, of all tasks, to a machine is deeply disheartening. What’s more, to farm it out to a machine that trawls the internet and cobbles together a fake version of you is not just academic dishonesty, it’s a broader degradation of our memories and our humanity. It’s demoralizing to think about talented young people outsourcing not only their creative labor but their life stories to a computer.

Yet it’s not the students who concern me most. The temptation to use A.I. as a shortcut is a symptom of a culture that has so devalued both writing and reading that it seems to some of my students like a rational choice to opt out of both.

More and more these days, expertise is scorned and so-called efficiency is prized above all else. But what if — as I am convinced — a fully formed person is not about optimizing productivity but rather about understanding and even embracing the messy inefficiencies of life? All the learning in a writing course occurs in those moments of struggle. The skills learned in a course like this are vital, because communicating and understanding the human condition will be essential long after the A.I. craze has passed.

This can feel like a battle already lost. The most common question I’m asked about my job by outsiders is whether students ever do their own writing. Most of them, as far as I can tell, do: They’re drafting, revising, stumbling, staying up late and getting frustrated and submitting the best work they can. They understand that the magic in a memoir comes about when a reader engages with the unique consciousness on the other side of the page.

An A.I. tool may learn how to superficially mimic the end result of writing, but it will never mimic a writer’s soul or how he or she actually produces meaningful writing — that process by which an individual idiosyncratic mind works out a problem, granting readers access to the inner life of another actual person, that constitutes the lifeblood of writing and storytelling.

I know the problem with A.I. will worsen over the coming years, as our institutions embrace a totally unproven technology. University administrators routinely announce new partnerships with A.I. startups, and well-meaning instructors — perhaps imagining an ideal student in an ideal world, or just wanting to feel like they’re on the cutting edge — incorporate these tools in their classrooms, even as the students come mainly to view them as easy shortcuts.

The only thing under my control as a teacher is what I do in my classroom. I will continue to teach students that, whether they go on to write a best-selling memoir or simply scribble in their journals occasionally, we can try to do the work as honestly and earnestly as possible, bringing our full obsessive selves to the page.

The act of writing itself can be an act of self-preservation, even one of defiance. That spark of rebellion is our greatest strength, and it’s found nowhere else but within us.

Tom McAllister is the author of four books, including the memoir “Bury Me in My Jersey” and a forthcoming essay collection, “It All Felt Impossible.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.