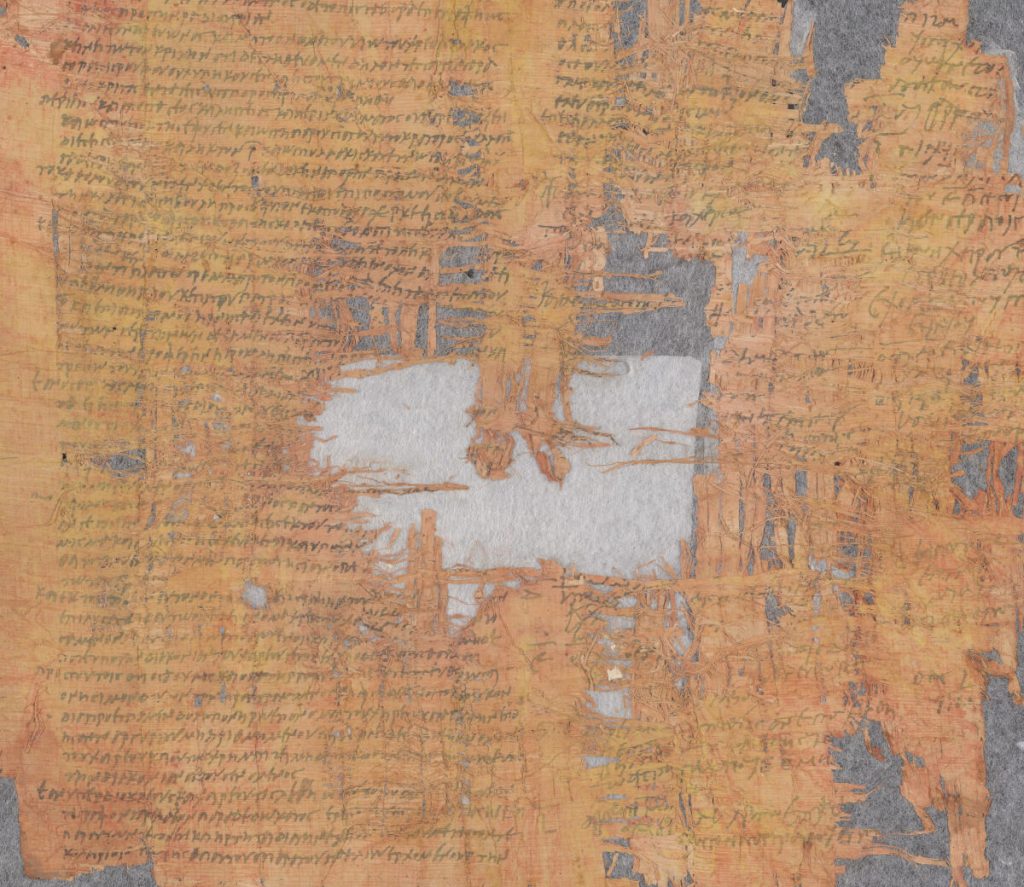

Papyrus Cotton (Credit: © Israel Antiquities Authority)

JERUSALEM — Sometimes the most significant historical discoveries happen by accident. When Professor Hannah Cotton Paltiel volunteered to organize documents at the Israel Antiquities Authority’s scrolls laboratory in 2014, she noticed something odd about a papyrus labeled as “Nabataean.” “It’s Greek to me!” she exclaimed — and she meant it literally. Her discovery would turn out to be the longest Greek papyrus ever found in the Judaean Desert, a remarkable document that reveals an ancient tale of financial crimes in the Roman Empire.

The 133-line text, now named “P. Cotton” in recognition of its discoverer, tells the story of two men accused of forging documents and evading taxes on slave transactions, a serious offense under Roman law. The case played out in what are now Israel and Jordan, against the backdrop of rising tensions between Rome and its Jewish subjects.

Recognizing the document’s extraordinary significance, Professor Cotton Paltiel assembled an international team including Dr. Anna Dolganov of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Professor Fritz Mitthof of the University of Vienna, and Dr. Avner Ecker of Hebrew University. Together, they determined that the papyrus contained prosecutors’ notes for a trial, along with hastily drafted transcripts of the actual court proceedings. “This papyrus is extraordinary because it provides direct insight into trial preparations in this part of the Roman Empire,” explains Dr. Dolganov. According to Dr. Ecker, “This is the best-documented Roman court case from Iudaea apart from the trial of Jesus.”

The defendants in this ancient legal drama were two men named Gadalias and Saulos. Gadalias was no ordinary citizen. As the son of a notary and possibly a Roman citizen himself, he had connections to the local administrative elite. But according to the prosecutors preparing their case against him, he had quite the rap sheet: accusations of violence, extortion, counterfeiting, and even inciting rebellion against Roman rule. His partner in crime, Saulos, orchestrated an intricate scheme involving the fictitious sale and manumission (freeing) of slaves to avoid paying imperial taxes.

The prosecutors’ memorandum reads almost like a modern legal strategy document, laying out detailed arguments and anticipating the defendants’ potential responses. For instance, they predicted that Gadalias would try to blame suspicious documents on his father, who had been a notary but was now deceased. The prosecutors prepared a sharp counter-argument: under Roman law, presenting forged documents in court was a crime unless proven to have been done in genuine ignorance.

The scheme itself was remarkably sophisticated. Saulos apparently chose Chaereas as his front man because Chaereas owed him money. In exchange for forgiving this debt, Chaereas agreed to act as the nominal purchaser of several slaves, including one named Onesimos. While the paperwork showed Chaereas as the owner, the slaves actually remained under Saulos’s control. Later, when Saulos wanted to free Onesimos, he had the manumission (freedom) documents drawn up in Chaereas’s name to avoid paying the substantial taxes normally required when freeing slaves.

“Forgery and tax fraud carried severe penalties under Roman law, including hard labor or even capital punishment,” explains Dr. Dolganov. The empire had elaborate systems for tracking slave ownership and collecting various taxes related to slave transactions, including a 4% tax on slave sales and a 5% tax on manumissions. These taxes provided significant revenue for the imperial treasury.

The court proceedings themselves, captured in hastily scribbled notes on the papyrus, reveal other fascinating details. A figure named Flaccus (possibly the presiding official) opens the proceedings by addressing Saulos directly. Later, someone named Primus is questioned about the truth of certain claims, and a slave called Abaskantos appears to undergo a lengthy interrogation. The notes also mention a substantial sum of 7,000 drachmas, though whether this represented the amount of evaded taxes, a fine, or something else remains unclear.

The timing and location of the case add another layer of intrigue. The events took place between two major Jewish uprisings against Roman rule: the Jewish Diaspora revolt (115–117 CE) and the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE). The text implicates both defendants in rebellious activities during Emperor Hadrian’s visit to the region in 129/130 CE. “Whether they were indeed involved in rebellion remains an open question, but the insinuation speaks to the charged atmosphere of the time,” notes Dr. Dolganov.

The case also raises puzzling questions about motives. As Dr. Ecker points out, “freeing slaves does not appear to be a profitable business model.” Some scholars speculate that the case may have involved the Jewish practice of redeeming enslaved Jews, but there is no definitive evidence to confirm this.

The papyrus offers unprecedented insights into Roman provincial administration. “This document shows that core Roman institutions documented in Egypt were also implemented throughout the empire,” notes Prof. Mitthof. It demonstrates how Rome maintained control through sophisticated legal and administrative systems, even in relatively remote regions.

What began with Professor Cotton Paltiel’s startled exclamation — “It’s Greek to me!”– has evolved into one of our most detailed windows into Roman legal and administrative practices. This accidental discovery demonstrates that even after decades of intensive study, ancient documents can still dramatically reshape our understanding of how empires managed their territories and dealt with financial crimes.

Paper Summary

Methodology

The research team employed multiple methods to analyze the papyrus. They first conducted a detailed physical examination, identifying different handwriting styles: the main text was written in a careful, professional hand, while the court notes were more hastily jotted down—similar to modern court transcripts.

The scholars also performed linguistic analysis, revealing that many Greek words in the text were used to translate Latin legal concepts. For instance, the Greek term rhadiourgía, typically meaning “mischief,” was specifically used in a legal sense to mean “fraud” in Roman law. Additionally, they cross-referenced the names and locations mentioned in the document with other historical sources, allowing them to place the case within the broader political and administrative landscape of the time.

Results and Analysis

Beyond documenting a specific legal case, the papyrus sheds light on how Rome administered justice in its provinces. One striking revelation is that Gadalias had been summoned to serve as a judge (xenokrites) on multiple occasions but failed to appear, citing financial hardship. This suggests that Rome required wealthy local elites to participate in legal proceedings, similar to jury duty today, but with financial qualifications.

The document also illustrates the empire’s investigative techniques. The prosecutors appear to have uncovered the fraud by cross-checking multiple records and possibly relying on informants. Their legal strategy was methodical, demonstrating Rome’s ability to enforce tax regulations even in distant provinces.

Limitations

Despite its excellent preservation, the papyrus presents challenges. The beginning is missing, so the full context of the case is unclear. Some sections are damaged, making certain passages difficult to decipher. Additionally, the rapid handwriting in the court notes adds to the difficulty of interpretation. Most frustratingly, the document does not reveal the trial’s verdict—perhaps because the outbreak of the Bar Kokhba revolt interrupted the proceedings.

Discussion and Takeaways

This discovery provides invaluable insights into Roman provincial law, taxation, and administration. It highlights the complexity of Roman bureaucracy and the lengths to which officials went to detect and punish financial crimes. It also offers new perspectives on Jewish-Roman relations, particularly in the years leading up to the Bar Kokhba revolt.

Funding and Disclosures

This research was conducted by scholars from the Austrian Academy of Sciences, the University of Vienna, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. No specific funding information was provided in the source materials.

Publication Information

Journal: Tyche (January 2025)

DOI: 10.25365/tyche-2023-38-5

Authors: Anna Dolganov, Fritz Mitthof, Hannah M. Cotton, Avner Ecker