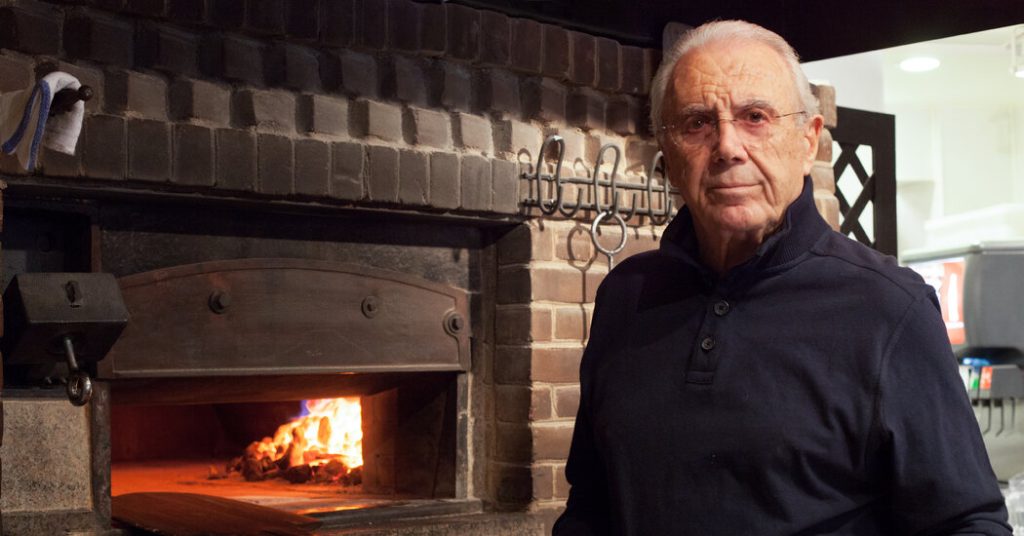

Patsy Grimaldi, a restaurateur whose coal-oven pizzeria in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge won new fans for New York City’s oldest pizza style with carefully made pies that helped start a national movement toward artisan pizza, died on Feb. 13 in Queens. He was 93.

His nephew Frederick Grimaldi confirmed the death, at NewYork-Presbyterian Queens hospital.

Mr. Grimaldi began selling pies in 1990 under the name Patsy’s. In those days, legal skirmishes periodically disturbed the city’s pizza landscape, and it wasn’t long before threatening letters from the lawyers of another Patsy’s led him to rename the place Patsy Grimaldi’s, then simply Grimaldi’s. Many years later, he reopened his restaurant with a name that pays tribute to his mother. Today that sign reads Juliana’s Pizza.

Under any name, Mr. Grimaldi’s pizzerias attracted long lines of diners outside, on Old Fulton Street, who were hungry for house-roasted peppers, white pools of fresh mozzarella and tender, delicate crusts baked in a matter of minutes by a scorching pile of anthracite coal.

Like the cooks he trained, Mr. Grimaldi hewed to the techniques he had learned in his early teens working at Patsy’s Pizzeria in East Harlem, owned by his uncle Pasquale Lancieri. Mr. Lancieri was one of a small fraternity of immigrants from Naples, including the founders of Totonno’s Pizzeria Napolitana in Brooklyn and John’s of Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village, who introduced New Yorkers to pizza in the early 20th century.

Mr. Grimaldi reached back to those origins when, after a long career as a waiter, he opened a place of his own with a newly built coal oven. At the same time, the minute attention he brought to his craft — picking up fennel sausage at a pork store in Queens every morning, for instance, while other pizzerias were buying theirs from big distributors — anticipated the legions of ingredient-focused pizzaioli who would follow him.

“It was the first artisan-style pizza” in the city, Anthony Mangieri, the owner of Una Pizza Napoletana in Lower Manhattan, said in an interview.

“He was really the first place that opened up that had that old-school connection but was thinking a little further ahead, a little more food-centric,” he said.

Patsy Frederick Grimaldi was born on Aug. 3, 1931, in the Bronx to Federico and Maria Juliana (Lancieri) Grimaldi, immigrants from southern Italy. His father, a music teacher and barber, died when Patsy was 12. To help support his mother and five siblings, Patsy worked at his uncle’s pizzeria, first as a busboy, then as an apprentice at the coal oven and eventually as a waiter in the dining room. Apart from a brief leave in the early 1950s to serve in the Army, he stayed until 1974.

Patsy’s Pizza kept late hours in those days, and Mr. Grimaldi grew adept at taking care of entertainers, mobsters, off-duty chefs and other creatures of the night, including Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, Rodney Dangerfield, Joe DiMaggio and Frank Sinatra.

The bond he formed with Mr. Sinatra lasted for decades. Mr. Grimaldi personally made deliveries from Patsy’s — two large sausage pies — when Mr. Sinatra stayed in his suite at the Waldorf Astoria. In 1953, they ran into each other in Hawaii, where Mr. Sinatra was filming “From Here to Eternity.”

“What are you doing here?” the singer asked the waiter. Mr. Grimaldi had been sent by the military to play bugle in an Army band.

Mr. Grimaldi met his wife-to-be, Carol, at a New York nightclub and took her to Patsy’s Pizza on their first date. They married in 1971.

A short time later, Mr. Grimaldi left Patsy’s to wait tables at a series of restaurants, including the Copacabana and the jazz club Jimmy Ryan’s. He was 57 and working at a Brooklyn waterfront cafe when he noticed an abandoned hardware store on Old Fulton Street with a “for rent” sign in the window and a pay phone bolted to a wall nearby. He picked up the phone and dialed the number. Not long after, he was showing off the nuanced, elemental pleasures of coal-fired pizza to people who had never tried it.

Matthew Grogan, an investment banker, ate at Patsy’s just a few weeks after it had opened. Until that moment, he thought he knew what good pizza was.

“I said, ‘I’ve been living a fraud all these years. This is the greatest food I’ve ever had,’” he recalled in an interview. (He later founded Juliana’s with the Grimaldis.)

Others seemed to agree, including critics, restaurant guide writers and customers. Some of them were well known, like Warren Beatty, who brought Annette Bening, his wife. (“So, are you in the movies, too?” Mrs. Grimaldi asked her.) Others were obscure until Mr. Grimaldi decided that they resembled someone famous. “Mel Gibson’s here tonight!” he would call out. Or: “Look, it’s Marisa Tomei!” He was more discreet when the actual Marisa Tomei walked in.

According to an unpublished history that Mrs. Grimaldi wrote, when the mob boss John Gotti was on trial in 1992 at the federal courthouse in Downtown Brooklyn, his lawyers became frequent takeout customers.

“We would wrap each slice in foil and they would put it in their attaché cases so that John would be able to have our pizza for lunch,” she wrote.

In 1998, the Grimaldis decided to sell the pizzeria to Frank Ciolli and try their hand at retirement. It didn’t last. Neither did their relationship with Mr. Ciolli, who opened a string of Grimaldi’s around the country that they believed failed to uphold the standards they had set in Brooklyn. When they learned that their old restaurant was being evicted, they snapped up the lease.

Mr. Ciolli, who moved Grimaldi’s to the building next door, sued to stop them from reopening. Mr. and Mrs. Grimaldi, he claimed in an affidavit, were trying to “steal back the very business they earlier sold to me.”

A truce was eventually reached. These days the lines outside Juliana’s are often indistinguishable from the lines outside Grimaldi’s.

Mr. Grimaldi is survived by his sister, Esther Massa; a daughter, Victoria Strickland; and a grandson. His wife died in 2014. A son, Pat, died in 2018.

An alcove at Juliana’s holds a small Sinatra shrine. The jukebox at its forerunner, Patsy’s (a.k.a. Patsy Grimaldi’s a.k.a. Grimaldi’s), was stocked with Sinatra records, interspersed with a few by Dean Martin. Mr. Grimaldi maintained a strict no-delivery policy with one exception: for Mr. Sinatra.