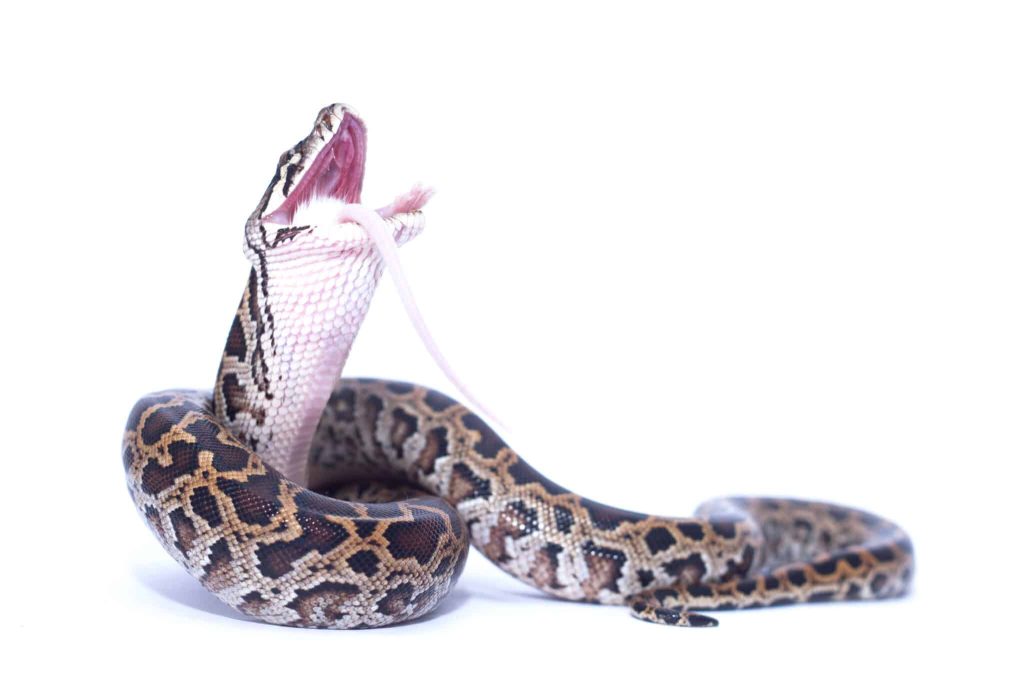

After each meal, python’s digestive systems go through an intriguing process. (Firman WahyudinShutterstock)

Could studying snake guts unlock new clues for treating digestive diseases?

In a nutshell

- Pythons regenerate their intestines after every meal. Unlike mammals, which rely on stem cell crypts for intestinal renewal, pythons completely rebuild their gut lining from scratch after fasting, using alternative cellular pathways.

- This regeneration process shares similarities with human gut adaptation. The genetic and molecular pathways activated in python digestion resemble those seen in humans after gastric bypass surgery, suggesting conserved mechanisms across species.

- Understanding how pythons regenerate their intestines could provide insights into treating conditions like Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, and post-surgical intestinal healing.

ARLINGTON, Texas — While most of us struggle with post-meal bloating, Burmese pythons take digestive expansion to another level. These snakes experience perhaps the most dramatic organ transformation known in vertebrates: their intestines physically rebuild themselves after each meal. Scientists have now mapped this remarkable process at the cellular level, revealing regenerative pathways that work without the specialized stem cells that mammals depend on. These findings may point toward unexpected parallels with human digestive adaptation.

A team of researchers led by scientists at the University of Texas at Arlington recently published findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) that show how pythons achieve this remarkable intestinal regeneration without intestinal crypts, which mammals depend on for their intestinal renewal.

How Mammal and Python Intestines Differ

Most vertebrates, especially mammals, maintain intestinal health through a renewal process centered around structures called crypts. Think of these crypts as tiny pockets in the intestinal wall that contain stem cells, versatile cells that can develop into different cell types. These stem cells constantly create new cells that travel upward to finger-like projections called villi, where they replace older cells that die off. It’s like a continuously running factory producing new cells to maintain the intestinal lining.

Pythons, however, completely lack these crypts, yet still achieve more dramatic intestinal regeneration than mammals.

“We used single-cell RNA sequencing to study intestinal regeneration in pythons and found that they use conserved pathways that are also found in humans, but activate them in unique ways,” says study author Todd Castoe, professor of biology at UT Arlington, in a statement.

In simpler terms, the researchers used advanced technology to examine which genes were being turned on in individual cells during different phases of the python’s digestive cycle. This created a detailed map showing exactly which cells were doing what during regeneration. They collected samples from fasting pythons and at several time points after feeding to track the sequence of cellular events that drive this remarkable transformation.

Special Cells That Drive Regeneration

Scientists discovered specific types of cells with crucial roles in this regenerative process. One type called BEST4+ cells (named after a protein they produce), acts as a central coordinator through a communication system called the NOTCH pathway. These cells send signals to other cell types, especially those forming vessels that transport fats from the intestine.

“These cells are present in pythons and humans, but absent in commonly studied mammals like mice, yet they act as central regulators of early phases of regeneration by promoting lipid transport and metabolism. These findings highlight the importance and largely neglected roles BEST4+ cells likely play in human intestinal function,” says Castoe.

The researchers also found a group of connective tissue cells that multiplies rapidly after feeding and guides the rebuilding of intestinal tissue. These cells activate genetic programs similar to those seen in embryonic development and wound healing, essentially reverting to early developmental programming to rebuild the organ.

From Python Digestion to Human Health

Many gene patterns activated during python intestinal regeneration resemble those seen in humans after certain medical procedures. The regenerative programs in pythons closely resemble intestinal changes that happen in humans after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB), a procedure used to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

During gastric bypass surgery, doctors reroute food to bypass part of the stomach and upper small intestine. This procedure often leads to remission of type 2 diabetes, even before significant weight loss occurs. Scientists have long wondered why this happens. This research on pythons shows that these snakes and humans may share ancient biological processes that help their intestines adapt.

The python intestine follows a predictable cycle. During fasting periods (which can last months), the intestine shrinks to a thin layer, saving energy. After feeding, it rapidly expands through coordinated activation of growth, metabolism, and stress response. By about two weeks after feeding, it returns to its fasted state, ready for the next meal.

Applications for Human Medicine

So, what does this mean for human health? Understanding how pythons regenerate their intestines could provide insight into intestinal healing after injury, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy. It might also reveal more about intestinal disorders like celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and potentially even intestinal cancers.

The humble laboratory mouse has dominated biomedical research for decades, but unusual animals with extreme adaptations are increasingly proving their scientific worth. Pythons won’t be replacing rodents in research facilities anytime soon, but their remarkable digestive flexibility is definitely piquing the interest of scientists studying digestive health. By piecing together regenerative strategies from across the animal kingdom, from standard laboratory mice to extraordinary pythons, scientists are assembling a more complete picture of what’s possible in tissue regeneration.

Paper Summary

Methodology

The researchers used two main techniques to study gene activity in python intestines. First, they performed bulk RNA sequencing—essentially measuring which genes were active across the entire tissue—at six timepoints: during fasting and at various intervals after feeding (6 hours to 6 days). Then, they used a more detailed technique called single-nucleus RNA sequencing at four key timepoints to identify which specific cell types were activating which genes. They also used antibody staining (similar to how we might use dye to make specific structures visible) to confirm the location of certain cell types in intestinal tissue samples.

Results

The study identified several cell types in the python intestine but found no evidence of traditional crypt stem cells. Cells called enterocytes (which absorb nutrients) showed dramatic changes in gene activity after feeding, with two major gene networks emerging: one involved in fat processing and another in stress response. BEST4+ cells were found to coordinate regeneration through cellular communication pathways. Connective tissue cells multiplied after feeding and activated both embryonic development and wound healing programs.

Limitations

The study used one python per timepoint for the detailed cell-level analysis, which limits understanding of individual variation. The researchers only examined the upper small intestine, which might not represent what happens throughout the digestive tract. While they identified correlations between signaling pathways and regeneration, they didn’t perform experiments to confirm these relationships cause the regenerative effects. Comparisons between python regeneration and human responses to gastric bypass surgery were based on similarities in gene activity rather than direct functional testing.

Discussion and Takeaways

The findings reveal that intestinal regeneration can occur without the specialized structures mammals use. The similarities between python regeneration and human responses to gastric bypass surgery suggest shared mechanisms that could explain why the surgery often resolves diabetes. BEST4+ cells, present in both pythons and humans but absent in commonly studied mice, may play important but previously unrecognized roles in human intestinal function. These discoveries could inform new treatment approaches for intestinal healing and metabolic disorders.

Funding and Disclosures

The research received support from the National Science Foundation (grant IOS-655735). All animal procedures followed approved protocols at the University of Alabama. The authors declared no competing interests.

Publication Information

The journal paper, “Single-cell resolution of intestinal regeneration in pythons without crypts illuminates conserved vertebrate regenerative mechanisms,” was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on October 18, 2024 (Vol. 121, No. 43, e2405463121).