Surveys in 36 countries find that Christianity and Buddhism have the biggest losses from ‘religious switching’

How we did this

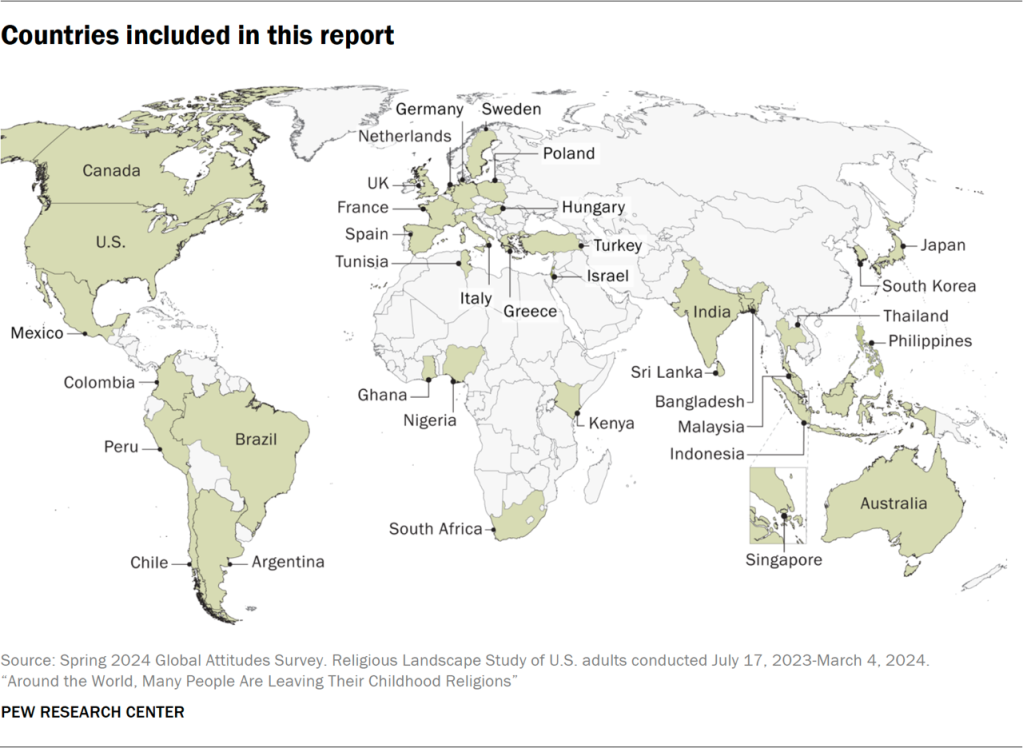

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to examine rates of religious switching in 36 countries across the Asia-Pacific region, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East-North Africa region, North America and sub-Saharan Africa. The countries have a variety of historically predominant religions, including Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam and Judaism.

For non-U.S. data, this analysis draws on nationally representative surveys of 41,503 adults conducted from Jan. 5 to May 22, 2024. All interviews were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Interviews were conducted face-to-face in Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ghana, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Tunisia and Turkey. In Australia, we used a mixed-mode probability-based online panel.

For the United States, data comes from the 2023-2024 Religious Landscape Study (RLS). The new RLS was conducted in English and Spanish from July 17, 2023, to March 4, 2024, among a nationally representative sample of 36,908 U.S. adults. Respondents had the option of completing the survey online, on paper, or by calling a toll-free number and completing the survey by telephone with an interviewer. The RLS was made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which received support from the Lilly Endowment Inc., Templeton Religion Trust, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations and the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust.

Here are the questions and responses used for this report, along with the survey methodology.

This analysis was produced by Pew Research Center as part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world. Funding for the Global Religious Futures project comes from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation (grant 63095). This publication does not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation.

Terminology

Throughout this report, religious switching refers to a change between the religious group in which a person says they were raised (during their childhood) and their religious identity now (in adulthood). The rates of religious switching are based on responses to two survey questions we asked of adults ages 18 and older:

- “What is your current religion, if any?”

- “Thinking about when you were a child, in what religion were you raised, if any?”

The responses to these two questions allow us to calculate what percentage of the public has left a religious group (or “switched out”) and what percentage has entered (or “switched in”). This kind of switching can take place without any formal rite or ceremony.

We have analyzed switching into and out of five widely recognized, worldwide religions to allow for consistent comparisons around the globe. Specifically, this report analyzes change between the following groups: Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, other religions, religiously unaffiliated adults, and those who did not answer the question.

For example, someone who was raised Buddhist but now identifies as Christian would be considered as having switched religions – as would someone who was raised Christian but is now unaffiliated.

However, switching within a religious tradition, such as between Catholicism and Protestantism, is not captured in this report. (Refer to Pew Research Center’s 2023-24 Religious Landscape Study for an analysis of switching in the United States that does count some switching within Christianity. Read “4 facts about religious switching within Judaism in Israel” for an analysis of switching within Judaism.)

Religiously unaffiliated refers to people who answer a question about their current religion (or their upbringing) by saying they are (or were raised as) atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.” This category is sometimes called “no religion” or “nones.”

Other religions is an umbrella category. It contains a wide variety of religions that are not in the other categories and that have survey sample sizes too small to analyze separately in most countries. This includes Sikhism, Jainism, the Baha’i faith, African traditional religions, Native American religious traditions, and others.

Disaffiliation rates refer to the percentage of adults who say they were raised in a religion but are now religiously unaffiliated (or have no religion).

Net gains/losses are the differences between the percentage of survey respondents who say they were raised in a particular religious category (as children) and the percentage who identify with that same category at the time of the survey (as adults). The “net” gain or loss takes into account both sides of the equation – those who have left and those who have entered the group.

Retention rates show, among all the people who say they were raised in a particular religious group, the percentage who still describe themselves as belonging to that group today.

Accession rates (also called entrance rates) show, among all the people who describe themselves as belonging to a particular religious group today, the percentage who were raised in some other group.

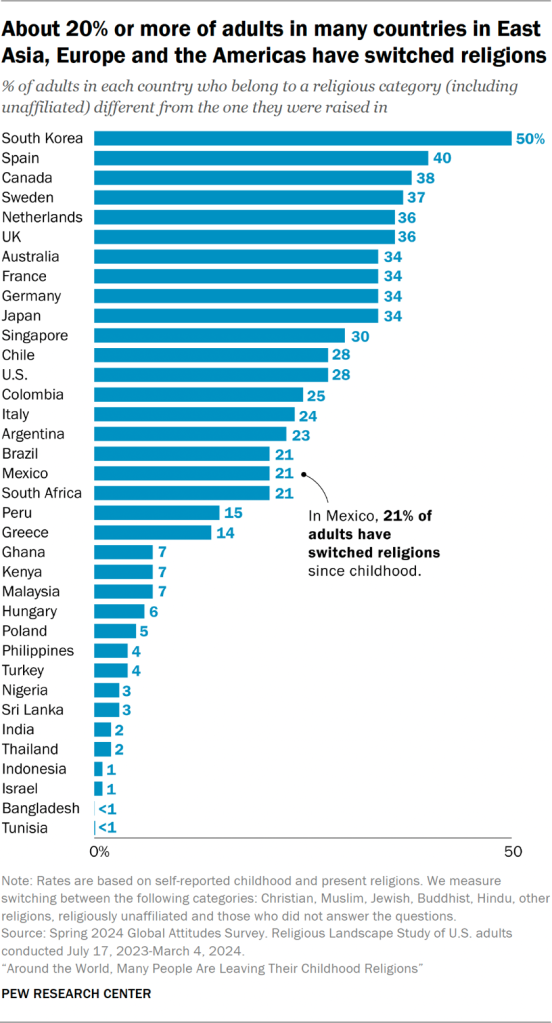

In many countries around the world, a fifth or more of all adults have left the religious group in which they were raised. Christianity and Buddhism have experienced especially large losses from this “religious switching,” while rising numbers of adults have no religious affiliation, according to Pew Research Center surveys of nearly 80,000 people in 36 countries.

Rates of religious switching vary widely around the globe, the surveys show.

What is religious switching?

Throughout this report, religious switching refers to a change between the religious group in which a person says they were raised (during their childhood) and their religious identity now (in adulthood).

We use the term religious switching instead of “conversion” because the changes can take place in many directions – including from having been raised in a religion to being unaffiliated.

We count changes between large religious categories (such as from Buddhist to Christian, or from Hindu to unaffiliated) but not switching within a world religion (such as from one Christian denomination to another). Refer to the Terminology section for details.

In some countries, changing religions is very rare. In India, Israel, Nigeria and Thailand, 95% or more of adults say they still belong to the religious group in which they were raised.

But across East Asia, Western Europe, North America and South America, switching is fairly common. For example, 50% of adults in South Korea, 36% in the Netherlands, 28% in the United States and 21% in Brazil no longer identify with their childhood religion.

Which religions are people switching to?

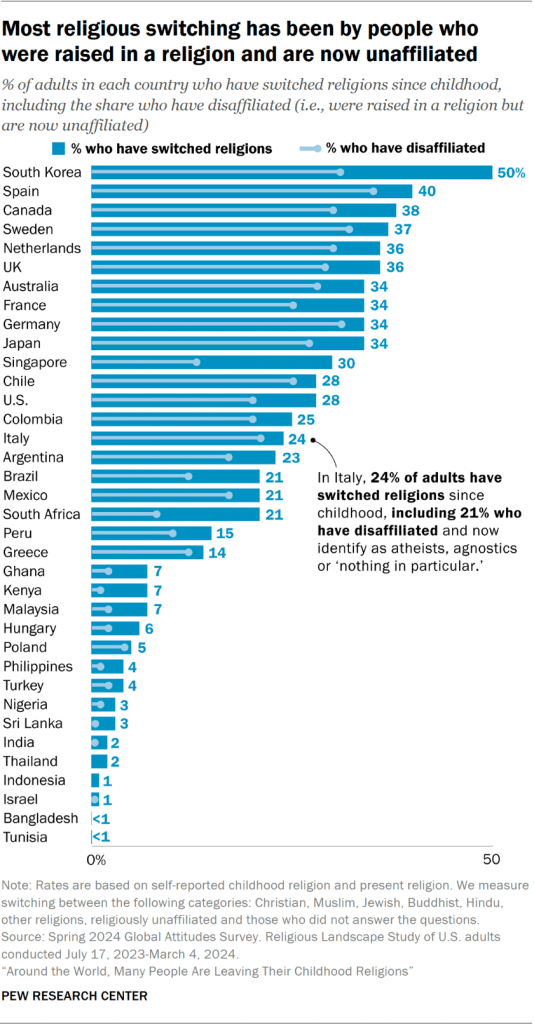

Most of the movement has been into the category we call religiously unaffiliated, which consists of people who answer a question about their religion by saying they are atheists, agnostics or “nothing in particular.”

In other words, most of the switching is disaffiliation – people leaving the religion of their childhood and no longer identifying with any religion.

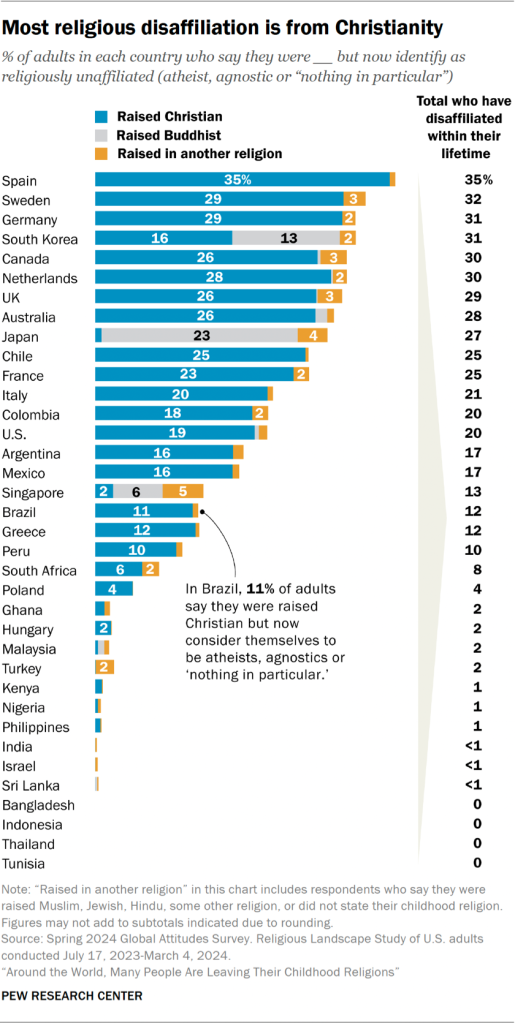

Many of these people were raised as Christians. For example, 29% of adults in Sweden say they were raised Christian but now describe themselves religiously as atheists, agnostics or “nothing in particular.”

Buddhism also is losing adherents through disaffiliation in some countries. For example, 23% of adults surveyed in Japan and 13% in South Korea say they were raised as Buddhists but don’t identify with any religion today.

However, not all switching is away from religion. Some people move in the opposite direction. Of the 36 countries surveyed, South Korea has the highest share of people who say they were raised with no affiliation but have a religion today (9%). Most of them (6% of all South Korean adults) say they had no religious upbringing and are now Christian.

Additionally, about one-in-ten or more adults in Singapore (13%), South Africa (12%) and South Korea (11%) have switched between two religions.

While these figures reflect religious trends in the 36 countries included in the survey, they are not necessarily representative of the entire world’s population. Christianity – the world’s largest and most geographically widespread religion, by Pew Research Center’s estimates – is either the current majority faith or historically has been a predominant religion in 25 of the countries surveyed.

Islam, the world’s second-largest religion, is a historically predominant religion in six of the 36 countries surveyed: Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nigeria, Tunisia and Turkey. (We consider both Christianity and Islam to predominate in Nigeria, which is closely divided religiously.)

Buddhism has been predominant in five other countries surveyed: Japan, Singapore, Sri Lanka, South Korea and Thailand. (We also count South Korea as having two predominant religions, Buddhism and Christianity.)

Hinduism and Judaism are each the predominant religion in just one country surveyed (India and Israel, respectively).

Other questions answered in this Overview:

Other factors driving religious change

This report focuses on religious switching. But switching is far from the only factor driving changes in the size of religious groups around the world. Other factors include migration rates (how many people in each religious group are moving into and out of a particular place); age structure (variations in the demographic makeup of religious groups by age and sex); fertility rates (the number of children born to women in different religious groups); and mortality rates (whether people in some religious groups live longer than others).

For example, across sub-Saharan Africa, the numbers of both Christians and Muslims are rising, largely because of high birth rates rather than switching. In the United States, the size of Muslim, Buddhist and Hindu populations are growing, due in large part to migration. And in some Western European countries, more Christians are now dying than being born each year, reflecting the continent’s low fertility rates.

Pew Research Center has published several global demographic studies looking at the interplay between all these factors and projecting the future growth rates of major world religions under various scenarios, including:

Which religious groups have experienced the largest losses from religious switching?

Another way of analyzing religious switching is to examine net gains and losses – how many people have entered and how many have left each religious group.

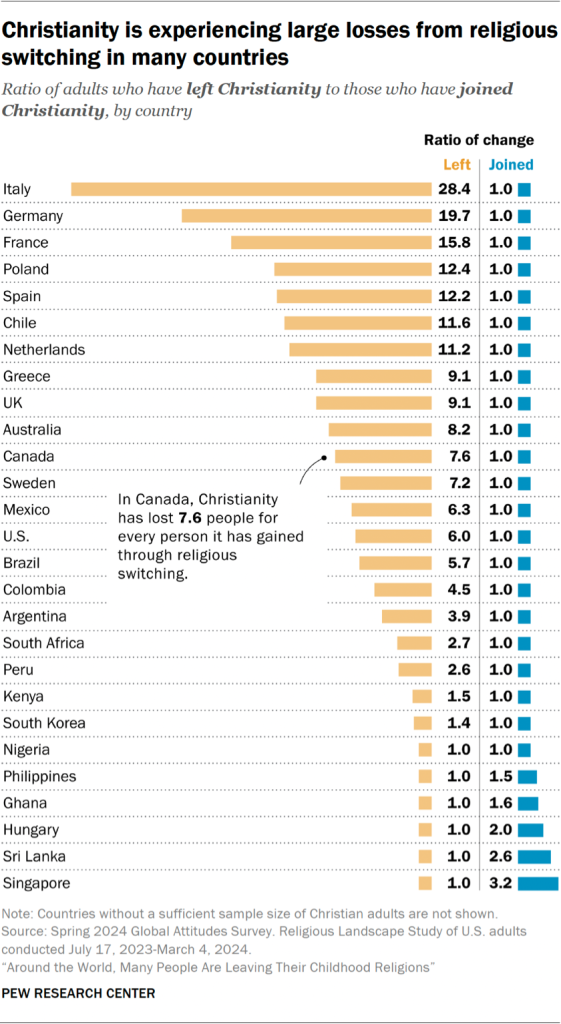

In most of the countries surveyed, Christianity has the highest ratios of people leaving to people joining – the largest net losses.

In Germany, for example, this ratio among Christians is 19.7 to 1.0, meaning there are nearly 20 Germans who say they were raised as Christians in childhood but don’t consider themselves Christian today for every one German who has become a Christian after being raised in another world religion or in no religion.

In a handful of countries, though, Christianity is making small gains from religious switching. In Singapore, for instance, the ratio among Christians is 1.0 to 3.2. For every Singaporean who has left Christianity, about three others have become Christians.

And in a few other places, roughly equal numbers of people are leaving and joining Christianity. For example, the ratio in Nigeria is 1.0 to 1.0.

(Read more about switching into and out of Christianity in Chapter 1.)

The survey also shows that Buddhism is experiencing large losses from religious switching – mostly disaffiliation – in a few countries, such as Japan, Singapore and South Korea.

However, the leaving-to-joining ratios are not as high as those for Christianity. For instance, in Japan – the country with the largest percentage of people who say they were raised Buddhist but are no longer Buddhists – the leaving-to-joining ratio among Buddhists is 11.7 to 1.0.

(Read more about switching into and out of Buddhism in Chapter 3.)

Which religious group has gained the most from religious switching?

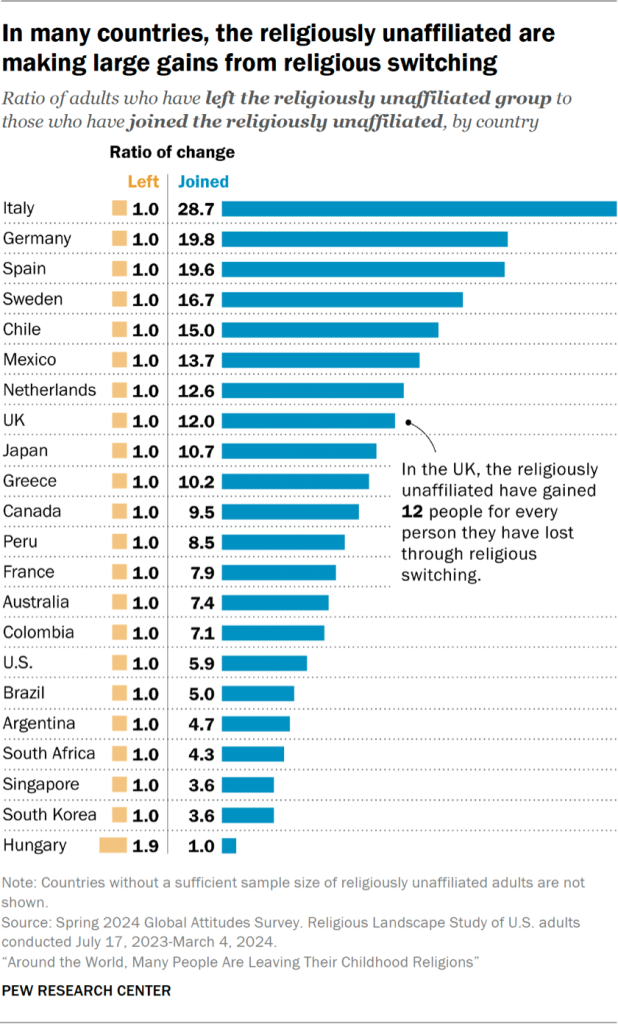

The category that has experienced the largest net gains from switching is the religiously unaffiliated.

In countries with substantial numbers of people who describe themselves as having no religion – sometimes called “nones” – many more survey respondents have become unaffiliated than have joined a religion after being raised without one.

In Italy, for example, the ratio of leaving to joining among the unaffiliated is 1.0 to 28.7. For every person who was raised without a religious affiliation but who now has a religion, more than 28 people say they were raised in a religion but no longer have one.

However, in Hungary, this is not the case. For every Hungarian who has become religiously unaffiliated, nearly two others say they were raised without a religion but now identify with one (a leaving-to-joining ratio of 1.9 to 1.0). Most of the Hungarians who have taken on a religion after being raised without one are now Christians.

(Read more about switching out of the religiously unaffiliated category in Chapter 2.)

Are there differences in religious switching rates by age, education or gender?

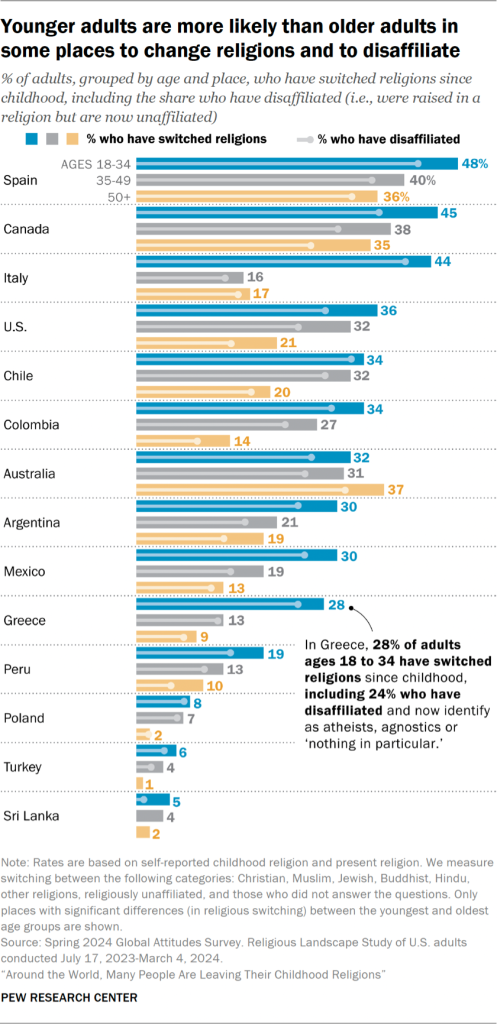

Age

In most countries surveyed, roughly equal percentages of younger and older adults have switched religions. For example, in Singapore, 29% of adults between the ages of 18 and 34 say they belong to a religious group that is different from the one in which they were raised, as do 29% of adults older than 50.

However, in 13 countries – including nearly all Latin American nations surveyed, as well as several countries in Europe and North America – adults under 35 are more likely than adults ages 50 and older to have switched religions.

In Spain, for instance, 48% of 18- to 34-year-olds have switched religions since childhood, compared with 36% of adults ages 50 and older. And in Colombia, 34% of the youngest adults have switched religions, compared with 14% of the oldest adults.

In Australia, however, younger adults are slightly less likely than older adults to have switched religions (32% vs. 37%).

In most cases, the bulk of the switching in all age groups is disaffiliation – much of which is people leaving Christianity. But the rates of disaffiliation are often higher among young adults. In Colombia, for example, 26% of 18- to 34-year-olds say they were raised as Christians but no longer identify with any religion, compared with 9% of Colombians ages 50 and older.

Because the survey questions pick up changes that have happened at any time since childhood, it is not possible to know whether the adults older than 50 who have disaffiliated did so recently or long ago, perhaps when they were in their teens or early 20s. Some older adults may have disaffiliated when they were young and then came back to a religion as they aged.

In short, these age patterns might be signs of secularization, indicating that countries like Spain, Canada, Italy and the U.S. are gradually becoming less religious. However, it’s also possible that some of the age differences in religious affiliation revealed in a single survey (or multiple surveys conducted at the same point in time) could result from people becoming more religious as they grow older.

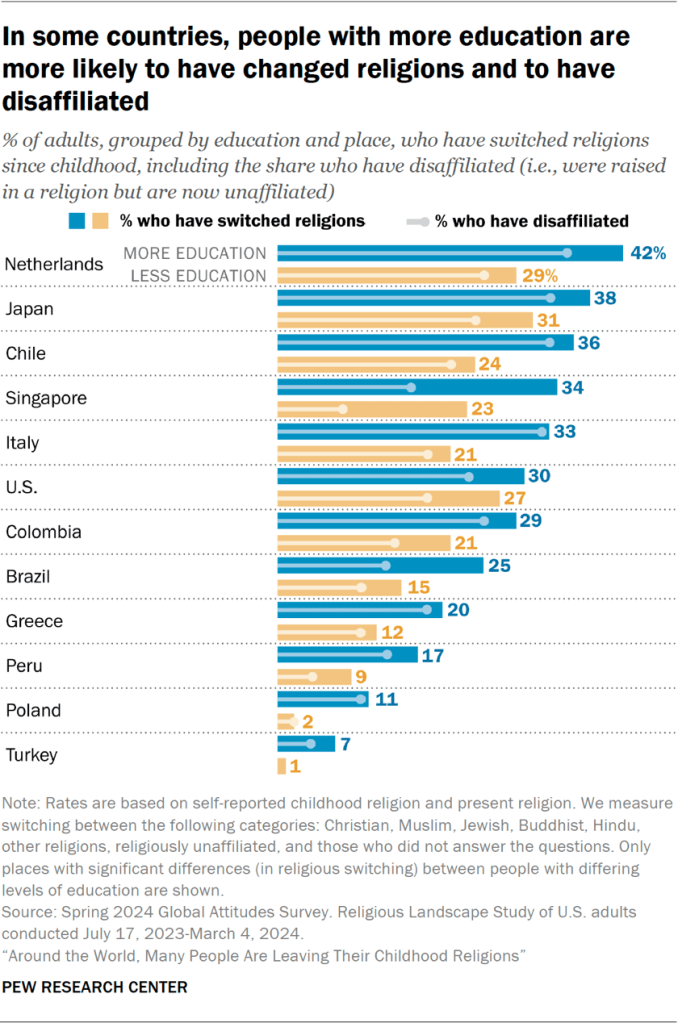

Education

In most countries, rates of religious switching don’t vary a great deal between people with different levels of education.

However, in 12 of the 36 countries surveyed, people with more education tend to have higher rates of religious switching.

Once again, most of the switching by people at each level of education is disaffiliation – in particular, people who say they were raised in a religious tradition (often as Christians or Buddhists) but no longer identify with any religion.

The Netherlands displays the largest differences in switching rates by education: 42% of Dutch adults with higher levels of education (a postsecondary degree or higher) have changed religions since childhood, compared with 29% of Dutch adults with lower levels of education.

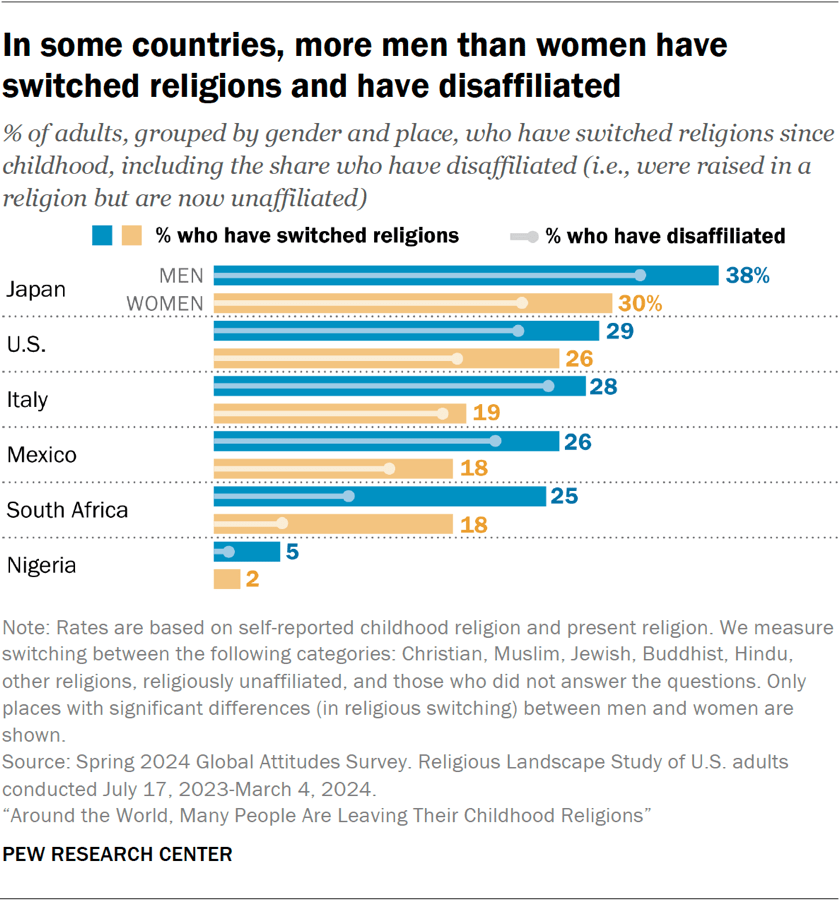

Gender

Likewise, in most countries surveyed, roughly equal percentages of women and men have changed religions. For instance, in South Korea – the country with the largest share of adults who have switched religions – 51% of women and 50% of men have changed religions over the course of their lives.

But in six countries, there are statistically significant differences in switching rates by gender, with men more likely than women to have switched religions.

And, as with the differences by age and education, much of the switching among both men and women is disaffiliation – especially from Christianity or, in Japan, from Buddhism.

Other key findings in this report

- Across the countries surveyed, most people who currently identify as Christian were raised as Christians. Among the smaller numbers who have become Christian after being brought up in a different way, most say they were raised as Buddhists or religiously unaffiliated. (Chapter 1 discusses switching into and out of Christianity.)

- Most adults who are now religiously unaffiliated say they were raised in some religion – in many cases, Christianity or Buddhism. (Chapter 2 covers switching into and out of the unaffiliated category.)

- In some countries, Buddhism has declined due to religious switching, while in other countries, it has remained relatively stable. (Chapter 3 examines switching into and out of Buddhism.)

- Very small percentages of the overall adult population have left or joined Islam in most of the countries surveyed. (Chapter 4 discusses switching into and out of Islam.)

- Most people who were raised Jewish in Israel and the U.S. still identify this way today, resulting in high Jewish retention rates in both countries. (Chapter 6 discusses switching into and out of Judaism.)

- Nearly all people who were raised Hindu in India and Bangladesh still identify as Hindu today. (Chapter 5 covers switching into and out of Hinduism.)