First published by Aperture in 1988, Sally Mann’s At Twelve, Portraits of Young Women is an intimate exploration of the complexities of the transition from girlhood to adulthood. Photographing in her native Rockbridge County, Virginia, Mann made portraits that capture the excitement and social possibilities of a tender age—while not shying away from alluding to experiences of abuse, poverty, or young pregnancy—and the girls in her photographs return the camera’s gaze with equanimity. On the occasion of Aperture’s reissue of the long sought-after volume, the writer Rebecca Bengal looks at At Twelve through a dozen reflections.

1.

Twelve. Auspicious and unrealized all at once. In English—on the heels of the sprinty lilt of eleven with its lucky seven-heaven rhyme—the sound of it is an awkward, monosyllabic clunk. It’s the last stop on the wheel of the clock, the year. Twelve, slant rhyming with elf, with wolf, a world of fairy tales. At twelve, still a girl, yet already preyed on by men. At twelve, split into a dozen selves.

2.

A cowgirl. A beauty queen in braces. The only girl on the softball team. Bathing suit, backyard, intransigent stare, one bare foot hooked protectively around the other. A sheath of dark bangs staring out from a painted Confederate battlefield. Businesslike in a blazer and skirt, a Persephone against a tree curiously bound with rope. In ribbons and lace, a belle perched on a patterned lounge, uncanny, unblinking, child and woman at once.

3.

Mann began making the At Twelve photographs in the early 1980s “in the odd hours … between jobs and diapers,” as she once put it (Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings, 2018). The making of the series, first published in 1988, spans the Reagan presidency. Now the pictures speak back and forth across thirty-seven years. Three times twelve, and one to grow on.

A reissue of a decades-old work, the surfacing of images from decades before prompts reexamination, rediscovery, primes us to look for what they reveal about the era of their making, what they augur about the world we live in now.

Details of the era creep in, markers and emblems of the ’80s: hairstyles, a digital wristwatch, Calvin Klein sweatshirt on a corduroy sofa, the early-generation Nike swoosh, checkerboard Vans flung on the sidewalk, a glass liter-size bottle of Tab. But what Mann sought to make is not documentary, not a work about its time. Nor is it about these girls as individuals, though particularities of their lives enter the frame. The true subject of At Twelve is time itself, perceptions of time and youth, about being a girl, versus a woman, about the chasm between those two phases, and what it means to cross them, and what selves are lost and what selves are inhabited in that process.

I grew up four hours’ south of the place of their making, several years after, now of course long past the age her photographs have crystallized the girls in them. But when I go back to these images, I instinctively inhabit twelve again.

4.

Consider the subtitle. Portraits of Young Women. Twelve, not yet a teenager, but already a young woman? At twelve, as a girl, that is what you do, project yourself years ahead. Novels and films you don’t understand fully yet, but also do. Eavesdropping. Watching. Project yourself, because the world is already projecting, seeing you as it chooses if you let it. Portraits of Young Women, because the pictures try on other, possible selves.

For instance: Draped over the hood of a car, DOOM drawn in the dirty finish. Arms flung around her mother, eight months along in the summer heat. Arms flung around herself, a shield against the make-out scene behind her. Among the clotheslines neatly hung with the jeans of eleven other siblings. Camouflaged in flowers. Caught in a spray of light, languid and also precarious on a swinging footbridge, water rushing below. Showing how her mom’s boyfriend once pretended to hang himself from a tire swing. Only the dog (the consciousness of the picture) shows his eyes.

Sally Mann: At Twelve, Portraits of Young Women

50.00

A long sought-after reissue of an American classic, with all-new tritone reproductions.

$50.0011Add to cart

In stock

Sally Mann: At Twelve, Portraits of Young Women

Photographs by Sally Mann. Commentaries by Sally Mann. Introduction by Ann Beattie.

Description

First published by Aperture in 1988, At Twelve: Portraits of Young Women is a groundbreaking classic by one of photography’s most renowned artists.

At Twelve is Sally Mann’s illuminating, collective portrait of twelve-year-old girls, taken in the artist’s native Rockbridge County, Virginia. The age of twelve brings tremendous excitement and social possibilities; it is a trying time as well, caught between childhood and adulthood, when the difference is not entirely understood. As Ann Beattie writes in her perceptive introduction maintained from the 1988 original publication, “These girls still exist in an innocent world in which a pose is only a pose—what adults make of that pose may be the issue.” The consequences of this misunderstanding can be real: destitution, abuse, unwanted pregnancy. Within this book of portraits, many of which are accompanied by writings of the artist, the young women in Mann’s unflinching large-format photographs, however, are not victims. They return the viewer’s gaze with a disturbing equanimity.

This reissue of At Twelve has been printed using new scans and separations from Mann’s prints, which were taken with an 8-by-10-inch view camera, rendering them with a quality true to the original edition.

Details

Format: Hardback

Number of pages: 56

Number of images: 36

Publication date: 2024-12-01

Measurements: 9.38 x 10.88 x 0.53 inches

ISBN: 9781597114585

Contributors

Sally Mann (born in Lexington, Virginia, 1951) is one of America’s most renowned photographers. She has received numerous awards, including NEA, NEH, and Guggenheim Foundation grants, and her work is held by major institutions internationally. Her many books include At Twelve (1988), Immediate Family (1992), Still Time (1994), What Remains (2003), Deep South (2005), Proud Flesh (2009), The Flesh and the Spirit (2010), Remembered Light (2016), and Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings (2018). In 2001 Mann was named “America’s Best Photographer” by Time magazine. A 1994 documentary about her work, Blood Ties, was nominated for an Academy Award and the feature film, What Remains, was nominated for an Emmy Award in 2008. Her best-selling memoir, Hold Still (Little, Brown, 2015), received universal critical acclaim, and was named a finalist for the National Book Award. Mann is represented by Gagosian, New York. She lives in Virginia.

Ann Beattie has been included in four O. Henry Prize collections. She has received the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story and the Rea Award for the Short Story, and she was the Edgar Allan Poe Professor of Literature and Creative Writing at the University of Virginia. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She currently lives in Maine, Virginia, and Florida.

5.

Once, as Mann recounts in her memoir Hold Still (2015), her teenage daughter Jessie gently schooled a person who worried unnecessarily how she’d feel at her mother’s art opening, out in public with a picture showing her naked body on the wall: “But that’s not me. That’s a photograph.”

The projected self is murky, a fiction. It’s a merger of the actual girl/woman, of the idea the actual presents for the photographer, of the interaction of the light and chemistry and invisible matter that transpires.

Consciously or not, the photographer seeks the twelves she might have become, those that might still exist within her. At Twelve is Mann’s second monograph, after the surreal The Lewis Law Portfolio (1977). Here she comes into her own as an artist, absorbing the influence of her mentor and friend Emmet Gowin (embracing the intimacy of the familiar) and her contemporary Nancy Rexroth (picturing the mythic in the familiar), and from numerous other masters of black-and-white photography, a stunning clarity, or what the novelist Reynolds Price described as Mann’s “serene technical brilliance.” Think of the book as a map, forking into divergent artistic paths, foreshadowing the work that would follow, the family pictures, the landscapes, the photographs of the human body altered by age and disease, decomposing and merging with the land.

6.

In the prologue to At Twelve, Mann writes that the portraits are equally about place. Lexington, Virginia, is itself an in-between; on the divide of North and South, mountains and ocean. It’s dominated by the mythic beauty of the Natural Bridge, a 215-foot geologic arch, the remains of an ancient cave, and it is soaked in Civil War bloodletting and the ruptures of colonialism and enslavement. The place where Mann had been a young girl, feral and country and clothing-averse, running down the road to chase after her family’s pack of dogs, pausing to pull hot tar from the asphalt to chew like gum. The place where she and her husband raised their three children. Twelve a natural bridge of its own. A crossing.

7.

This was her, Mick Kelly, walking in the daytime and by herself at night. In the hot sun and in the dark with all the plans and feelings. This music was her—the real plain her . . . This music did not take a long time or a short time. It did not have anything to do with time going by at all. She sat with her arms around her legs, biting her salty knee very hard. The whole world was this symphony, and there was not enough of her to listen.

—Carson McCullers, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter (1940)

Mann precedes the book with a picture of herself at twelve, and a quote from Anne Frank: “Who would ever think that so much can go on in the soul of a teenage girl?” But I think of Mick, thirteen in the Georgia of McCullers’s novel, “at the age when she looked as much like an overgrown boy as a girl,” besotted with the music of a composer she knows as “Motsart,” overwhelmed by desire. “I want—I want—I want—but what this want was she did not know.”

Carson McCullers was just twenty-three when her debut novel was published to success that overwhelmed the author as much as her character; not long after, McCullers was spending time in Lexington where, as Mann recalls in Hold Still, “she was once hauled out of a bathtub at a mutual friend’s house by my mother, drunk, drenched, and fully clothed.”

Throughout At Twelve, affixed to the photographs are Mann’s short texts, alluding to stories outside the frame: the girl who made paper flowers to line the walk to the family outhouse, who in a couple short years would’ve “gone and gotten herself a baby,” but at twelve just liked to ride around listening to the radio. Setting words to whatever music played in the heads of these girls.

8.

In Hold Still, published nearly forty years after she began the At Twelve photographs, Mann seeks to posthumously get to know her father, a deeply private, death-obsessed Texan who’d harbored his own secret artistic desires, yet opened a medical practice and passed his camera on to his daughter. But she launched that investigation in these pictures, drawing on the connections her father made within the rural community, families whose babies he delivered. Her own drives to make her large format portraits echo a doctor’s rounds. Here are lives just a few miles from her own. Theresa, pregnant at eleven, a mother at twelve, protectively watching her baby daughter who rests outstretched on her blanket, a newborn amid a bedroom full of raggedy, well-loved baby dolls. She has, Mann’s caption tells us, “already begun to shoulder the weight of adult reality.”

9.

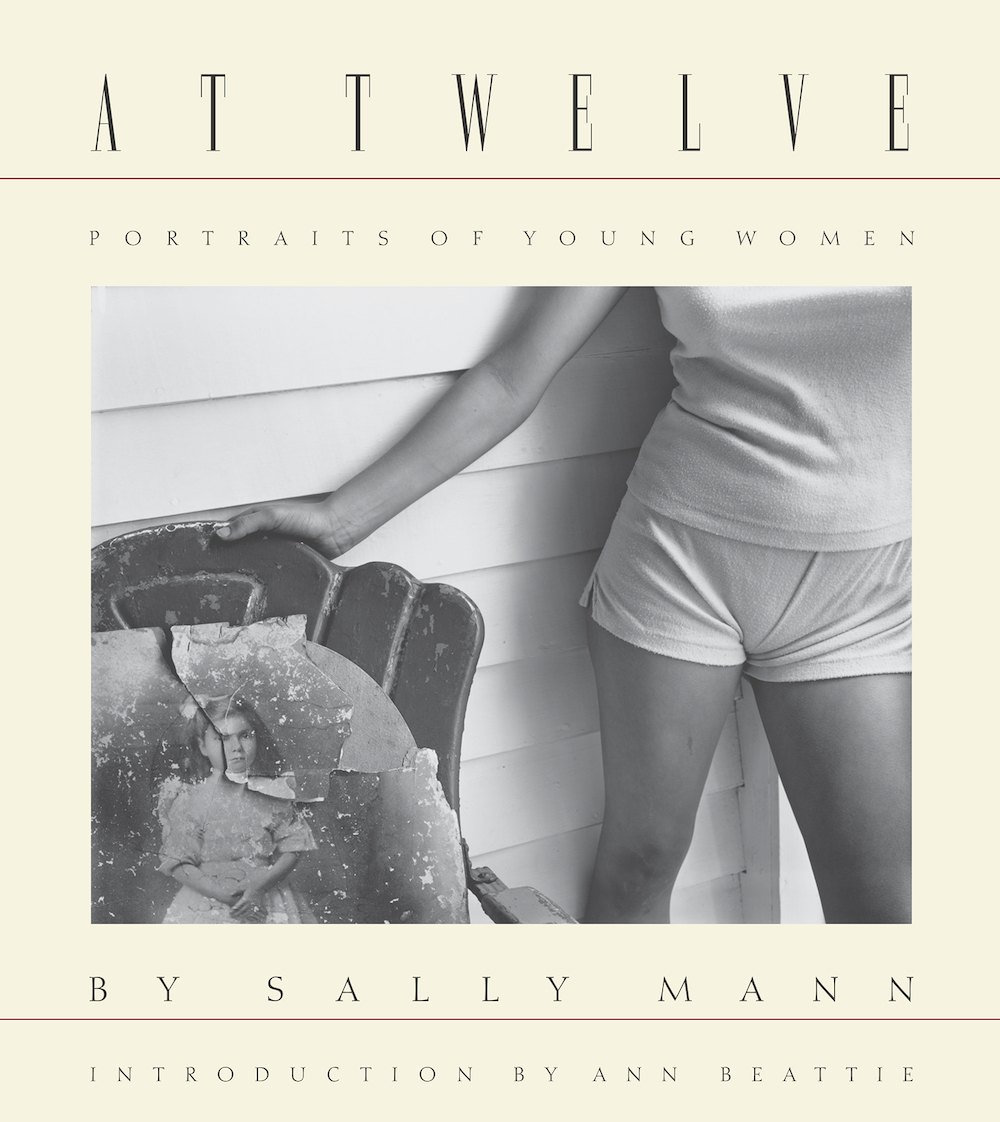

They pose with images of other girls and young women. On the cover of At Twelve: Torso and cocked hip in the 1980s present, a hand gestures toward an inevitably decaying photograph of another girl, late-nineteenth century maybe, a long-gone relative maybe, a crack running through her hair ribbon, down the side of her face, through the puffed sleeve of her white dress. Because the photograph shows only the midsection of the ’80s girl, we see the face of history as her own.

In the book’s interior: Two sisters posed against a portrait of their doppelgänger ancestors. Window reflections in the portrait, so much light the faces in it begin to dissolve as by time itself. The gaze of the sisters in the shadowy present. The portrait-within-a-portrait both a past and a future.

10.

Mann writes in Hold Still that photographs destroy memory. Some truth to that. Regardless, her At Twelve photographs also show how the camera (and time) still have the power to reveal things unperceived in the moment. It’s a testament to the strength of these pictures that, looking at them now, you can’t help but wonder how Mann didn’t consciously apprehend what lay below their surfaces. And yet, as most artists can attest, at some point the act of making work produces its own fugue state; it is not possible to see it in totality, or near totality, until later, sometimes much later. For a photographer, lost in the black vacuum under the hood of the camera, the world turned upside down and backwards in the ground glass, so many details flickering in the span of a shutter, the full picture clear only via photography’s more useful metaphors: being developed and processed.

11.

On the page laid bare: The stiffened posture, the distance a twelve-year-old refused to bridge to pose with her mother’s boyfriend. Mann’s text tells us the girl’s mother later shot him in the face; the picture, which in retrospect the photographer sees with “a jaggy chill of realization,” suggests why. On the porch of a life-size playhouse, the dark shadow of a father looms behind his daughter as he exacts an awkward and menacing grip on her arm. Unsettling, the way they both dwarf the little-girl tea-party furniture, Alice in Wonderland proportions. Mann affixes a reference from Lewis Carroll, whose own relationship with young girls was dubious. But the imprint of darkness bears out here too.

© the artist

12.

In At Twelve, the eyes are the punctum. Mann dwells on the “knowing watchfulness” of the gazes of the twelve-year-olds in her frame, the way they disarm; how, for the photographer studying her own prints, the eyes are “sibylline, foreboding,” possessing a “direct, even provocative approach to the camera.” The eyes meet the lens, an acknowledgment: that the picture they are participating in is not-them, but also, that they have permitted something of their own selves to be seen.

In the parting frame, slouched on (her father’s?) lap around an outdoor table of adults and drinks, relaxed, faces blurred or obscured. Only hers sees and is seen fully by the camera. Her brows raised, her eyes unflinching, questioning the photographer’s stare, our own. In her eyes—in all their eyes—is the assertion of the self, the power of the self.

Looking again at these pictures we intuit how much change lies ahead for each of them, on the cusp of becoming women. And yet, also clear: how very precious little change has occurred in the eyes of men.

This is not a sociological body of work. But we are in the midst of a deeply darkening age of politics for freedom of speech, and for women, for girls, for whomever the women and girls in these portraits might identify as, and it is difficult not to view it now without also drawing a line between the repression of our own era, and theirs, to all time. The young women in these pictures understand this too.